In 2011, under a bright yellow and white stripped awning which protected those gathered for lunch from the the hot July sun in Geneva, Switzerland, a group of unlikely companions sat down to share a meal. The guests were gathered around the table by events that had crossed both centuries of time, and empires laid ruined by revolution. They were assembled by the grace of a spiritual thread that bound them in an inexcplicable way.

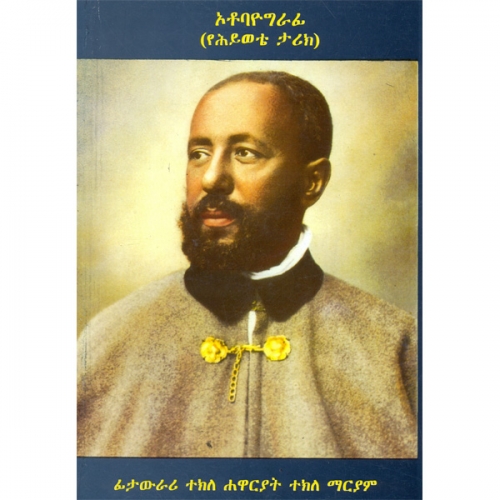

At the head of the table sat Her Imperial Highness Princess Adey Imru Makonnen, the widow of HIH Prince Dawit Makonnen (Makonnen Makonnen) (who was the son of Prince Makonnen Haile Selassie, Duke of Harar (1924-1957), the second youngest son of HIM Emperor Haile Selassie ( Lij Tafari Makonnen WoldemikaelI) (1892 -1975) and HIM Empress Menen Asfaw (Walatte Giyorgis) (1891-1962)). Next to her sat Sahle Mariam Endeshaw, she was not only the great grandaughter of our protaganist, Fitawrari Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam (adopted name in Russia: Piotr Sergeievitch Tekle-Hawariate (Molchanov) / Петр Сергеевич Тэкле-Хавариате (Молчанов) (c1884-1977), but a relative of the late Emperor Haile Selassie I and for fans of Reggae Pop, she is also a singer known as the real Sheba (www.therealsheba.com). Across the table was Weynabebe Abate, the daughter of an Ethiopian diplomat and a descendant of a noble Ethiopian family who was a childhood friend of Anna Kotchoubey (née Huchberger), the hostess. Finally, at the other end of the table sat the great great grandson of Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna Kotchoubey (née princess Volkonskaya) / Елена “Нелли” Сергеевна (Волконская) (1835 – 1916) who was the adopted grandmother of Fitawrari Begirond Tekle Hawariat whom he got to know towards the end of her life, wheel chair bound but still full of life. Two little children at the table, Constantin Alexandrovitch and Anastasia Alexandrovna could not have cared less about the circumstances of the gathering except that sitting in their midst was a breakout singer, Sheba Sahlemariam whose song “Love This Lifetime” (see: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ka7y0rHzYnE) was playing daily on the radio and had been part of the family’s iTunes collection.

A Prophetic Journey to Ethiopia undertaken by Nikolai Leontiev:

The story begins with the adventures of Nikolai Stepanovitch Leontiev / Николай Степанович Леонтьев (1862-1910), who born in the Kherson province to a minor noble family became a soldier, an explorer and an adventurer who helped to open Russian-Ethiopian ties at the end of the 19th century. The craze for Ethiopia seized the imagination of St. Petersburg society towards the 1870s-1880s and Leontiev finally set out on an expedition to Ethiopia with the support and interests of the Russian Geographical Society, and the Academy of Sciences and a number of other sponsors which included the Russian Red Cross. In addition, the two countries were unified as brother nations in the Orthodox confession. When he arrived in Ethiopia, the newly created Italian Kingdom was engaged in the first of many conflicts which would eventually become known as the First Italo-Ethiopian War.

Leontiev was hardly the first Russian in the region.

Leontiev was introduced to the reigning Emperor Menelik II, Negus of Shewa and then Negusa Nagast-King of Kings (baptized as Sahle Maryam) (1844-1913), who would become an important actor in the development of Russo-Ethiopian relations and the person most responsible for the gathering of the unlikely luncheon companions in Geneva in 2011. A deeply religious man, Menelik II was often found at prayer in the evenings and he would be supported in his spiritual jouney by members of his retinue who would read the prayers on his behalf. Amongst the retinue was a young boy born in 1884 and at the time not older than nine years old who read the scriptures in such a sweet and melodic fashion that he was soon the Emperor’s favorite reader. The boy had the good fortune to be born in Shewa and he received his intial education in the church. The little boy, called Tekle, was under the patronage of Ras Mäkonnen Wäldä-Mika’él (1852 – 1906), the first cousin of Menelik II. Ras Makonnen was a general and then governor of Harar Province and the father of the future Emperor Haile Selassie I. He was also the first to welcome Leontiev in Harar and facilitated the friendship with his cousin Menelik II and the man who would indirectly shape Tekle Hawariat important life.

Emperor Menelik II engages the Russians:

So taken was Menelik II with Leontiev when he arrived on his expedition in 1894, that he quickly understood that in addition to friendly relationships that were established, there was a strategic role that Russia could play in fighting the aggressions of the colonial Italian army which was about to wage war. Menelik’s court worked diligently in preparing a delegation that would accompany Leontiev back to St. Petersburg in June 1895 and it was understood that this might help pave the way for further cooperation between the two empires. The Ethiopian delegation included Menelik II personal secretary, Ato-Iosiph, members of his family, Prince Damto, Prince Beylakio, as well as military attachés, led by General Genemier and representatives of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo, represented by the Bishop of Harer, Gebraux Xavie.

Tekle Hawariat a 12 year old bridge between two Empires:

When the delegation arrived in St. Petersburg they were celebrated and feted throughout the capital. Leontiev was their guide and for 40 days they were led through all the grandest homes and places in the capital (see: Article on Ethipoia & Russia in St. Petersburg). The excitiement for Ethiopia had taken on a new dimension, fuelled by newspaper articles written by such journalists like Yury Lukianovitch Eletz /Юлий Лукьянович Елец(1862-1932) and Leontiev played a great role in insuring the success of the fruits of his mission to Ethiopia.

Leontiev returned with the delgation to Ethiopia bringing with him much needed arms and ammunition and his timing could not have been better as Menelik II was in full conflict with the Italians. The arrival of Leontiev with fellow military officers, as well, quickly turned the conflict in favor of Menelik II who had been struggling against the more sophisticated weapons of the Italian forces. With word spreading amongst the courtiers of the successful trip to St. Petersburg and the friendships and alliances that could be born, there was much discussion about sending young members of the court to be educated in St. Petersburg.

Accompanying Leontiev back to Ethiopia in 1896 following the visit of the Ethiopians to St. Petersburg was Colonel Sergei Dmitrievitch Molchanov / Сергей Дмитриевич Молчанов (1853-1905). Sergei was the son of a minor nobleman and Siberian bureaucrat Dmitri Vassilievitch Molchanov / Дмитрий Васильевич Молчанов (-1857) whose greatest legacy may have been the fact that his first and only wife was Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna Molchanova (née princess Volkonskaya) (1835-1916), the daughter of the Decmebrist Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volokonsky / Сергей Григорьевич Волконский (1788 – 1865). Nelly left Irkutsk, soon after the death of her husband Dmitri in 1957. His death was little consolation to the young princess, a widow at 22 years old, as she was left with a young toddler and a memory of the last years of her husband who had fallen into disgrace after being accused of bribery. After a long and arduous journey from Siberia which would be her last time in the the vast stretches of the Siberian plains, the young widow arrived with her five year old son and her parents in European Russia. Once back in European Russia she met, fell in love and was remarried to Nikolai Arkadievitch Kotchoubey / Николай Аркадьевич Кочубей (1827 – 1868). She and her paerents moved to his estate of Voronki in Malorussia., which ultimately became home for young Tekle.

With time, her little Sergei like all sons of the nobility when he reached the age of seven, was sent to St. Petersburg to be educated at a military academy. There he found his other family and dedicated his life to his career as an officer in the prestigious and storied Russian regiment of His Majesty’s Life Guard Hussar Regiment /Лейб-гвардии Гусарский Его Величества полк.

Peter the Great’s Abyssinian paves the way…

Years later, already a colonel in his regiment. the frenzy over Leontiev’s Abyssian delegation was not lost on Sergei who, seized the opportunity to travel back with a number of his fellow officers to Ethiopia. Was it for a taste of adventure? The thrill of finding a fair fight or a chance to escape the boredom and routine of a regimental officers life is not clear. He was, afterall an unmarried career soldier with no immediate family and the opportunity to visit Abyssinia was a gripping opportunity for the old fun-loving bachelor officer.

Perhaps his attraction to Abyssinia was a cruel joke that history played on the poor fun loving hussar for not less than seventy years before, his grandmother princess Maria Nikolaevna Volkonskaya (née Raevskaya) / Мария Николаевна Раевская (Волконская) (1805 -1863) the daughter of the Napoleonic war hero and of the Battle of Borodino, General Nikolai Nikolaivitch Raevsky / Николай Николаевич Раевский (1771 – 1829) was the object of affection of Russia’s second most famous Abyssinian, the poet Alexander Sergeievitch Pushkin / Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (1799 -1837). Pushkin with his wavy black hair and protruding features was said to have shown with no doubt that he was the great-grandson of Peter the Great’s famed Abyssinian General Abraham Petrovich Hannibal / Абрам (Ибрагим) Петрович Ганнибал (1696 – 1781). It was an error of ignorance among contemporary chroniclers that Pushkin and his great-grandfather were referred to as Abyssinians as it was not at all clear from where in Africa, Hannibal had, in fact, come. Some scholars believe that Peter’s General Hannibal was in fact of either Ghanian origin or from Central Africa. He was said to have been sold into slavery and then brought to Constantinople where he was eventually bought by Peter’s ambassador to the Ottoman Porte, Count Sava Vladislavitch Raguzinsky / Сава Владиславић Рагузински (1669-1738). This argument was further supported by the presence of a white elephant on Hannibal’s coat of arms, a symbol of the kings of the Denkyira Kingdom who are part of the Akan people in present day Ghana.

What ever the truth of their origins, Hannibal and his great-grandson Alexander Pushkin were Russia’s most famous Abyssinians and Alexander had spent many wonderful summers in Kamenka, the estate of the Davydov family that belonged to Maria Raevskaya’s grandmother, Ekaterina Nikolaevna Raevskaya – Davydova (née Samoilova) / Екатерина Николаевна Самойлова (Раевская, Давыдова) (1750 -1825) who remarried after the death of Col. Nikolai Semionovitch Raevsky /Николай Сёменович Раевский (1741 -1771) at a battle during the Azov campaigns, Lev Denisovitch Davydov / Лев Денисович Давыдов (1743 -1801). Alexander the master wordsmith and hapless romantic spent hours reflecting about his love for Maria and today we are left with some of the loveliest poems in her honour.

Once in Abyssinia, Sergei along with other senior officers met the Emperor Menelik II and worked with him to execute the plans against the Italian forces. In his book, Journal of an expedition from Ethiopia to Lake Rudolf by Alexander K. Bulatovich which was a disasterous expedition for the Russians undertaken in 1897, the author thanked Sergei Molchanov in his preface. Bulatovich joined the Hussars in 1891-92 as an enlisted soldier and would have met Sergei Molchanov in the inervening years. What is less clear is why he would have thanked Molchanov for his assistance if the Colonel had not had expertise on Abyssinia by actually traveling there the year before. He writes (translated by Richard Seltzer in 1993, See: Article on Lake Randolf Expedition)…

…Bringing this preface to a close, I consider it my duty to thank the Chief of the Military Printing Office Lieutenant-General Otto von Stubendorf, the Chief of the Geodesic Office Major-General Iliodor Ivanovich Pomerantsev, the Chief of the Cartographic Department Major-General Andrey Alexandrovich Bolshov, and Colonel of His Majesty’s Life-Guard Hussar Regiment Sergei Dmitrievich Molchanov. Owing to their enlightened cooperation and valuable advice, I was able to bring the present work to a satisfactory conclusion. I want to express my deep and respectful gratitude for their help.

More importantly, Molchanov must have spent time with Leontiev’s old friend, Ras Makonnen. Ethiopia was modernizing and it was embarking on a path that would need a new generation of western educated elite to lead the country. No one understood this better than Ras Makonnen who was certainly well introduced to European traditions and culture. He was a friend of the French poet and adventurer Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) and by the turn of the following century he would attend King Edward VII’s coronation and visit a number of European countries. It was with this spirit, that Tekle Hawariat shares in a brief interview in a Soviet Era documentary on Ethiopia called Burnt by the Sun / Обожженные солнцем (1965) (minutes 39:20 to 41: 20) how he arrived in St. Petersburg having been sent by Ras Makonnen in 1896 at the age of 11 and met by chance a colonel Molchanov who immediately handed the job of educating Tekle into the hands of his mother, now newly married for a third time and known as “Nelly” Rakhmanova.

There were five Ethiopian boys who were sent to Russia. While Tekle describes the meeting with his soon-to-be adoptive father as a meeting of chance, it is difficult to believe that this was nothing more than a planned enocounter which was linked to Molchanov’s activities in Abyssinia and his connection to Col. Leontiev. Young Tekle, as a twelve year old boy wrote that he was present at the Battle of Adwa which was concluded on March 1, 1896 and where the Ethiopian forces supported by Russian weapons and military advisors were victorious over the Italians. So Tekle met Molchanov in St. Petersburg in late 1896 or early 1897. The documentarym Burnt by the Son prefaces the interview with Tekle by stating that he arrived in 1896, a date that would have been confirmed by Tekle himself. He traveled with a delegation of the Russian Red Cross under Col. Leontiev’s (Count Abai as of 1897) protection. This detail is further reinforced by the fact that in official correspondences with the Russian military Academy administrators, Tekle is referred to by Molchanov as the son of Abai, a reference most likely to Nikolai Leontiev’s recently created Ethiopian title of Count Abai. The journey to Russia, whatever the circumstances must have been a terryfying moment for young Tekle but after all, he was chosen for a special path in life.

When Sergei returned back from Ethiopia, more enthusiastic then ever before, he first went through the important steps of officially becoming a guardian for his new ward. So passionate was Sergei about Ethiopia and his new ward that he authored an article in November 1896 entitled, “the Meaning of Abyssinia/ Значение Абиссинии” in the “St. Petersburg News / Санкт-Петербургских ведомостях» от 13 ноября 1896 г, № 315.

The young Abyssinian, Tekle Hawariat Mariam Hawariat arrived on the estate of his adoptive family in early 1897 and was welcomed with open arms. In addition to his new cousins the Kotchoubey brothers and their sister Elena, he had two two new aunts and a loving grandmother. He maintained his Ethiopian travel papers or passport during his stay in Russia and while Sergei became his guardian in more ways then none he was also Tekle’s father and mentor. In Russian archives, Tekle’s name is mentioned in different ways and while in some genealogical sites he is refered to as Piotr Sergeievitch Molchanov / Петр Сергеевич Молчанов, in the military school records he would be known as Piotr Tekle-Hawariate, son of Abai. This was a nod to his Ethiopian heritage while the reference to son of Abai, may have come from the association to Leontiev and his title Count of Abai. Regardless of these technicalalities which are useful for historians looking within Russian archives to his Russian family he was known as Petya the Abyssinian (Petia Abissinetz). Tekle would forever refer to Sergei as his father and Nelly as his grandmother.

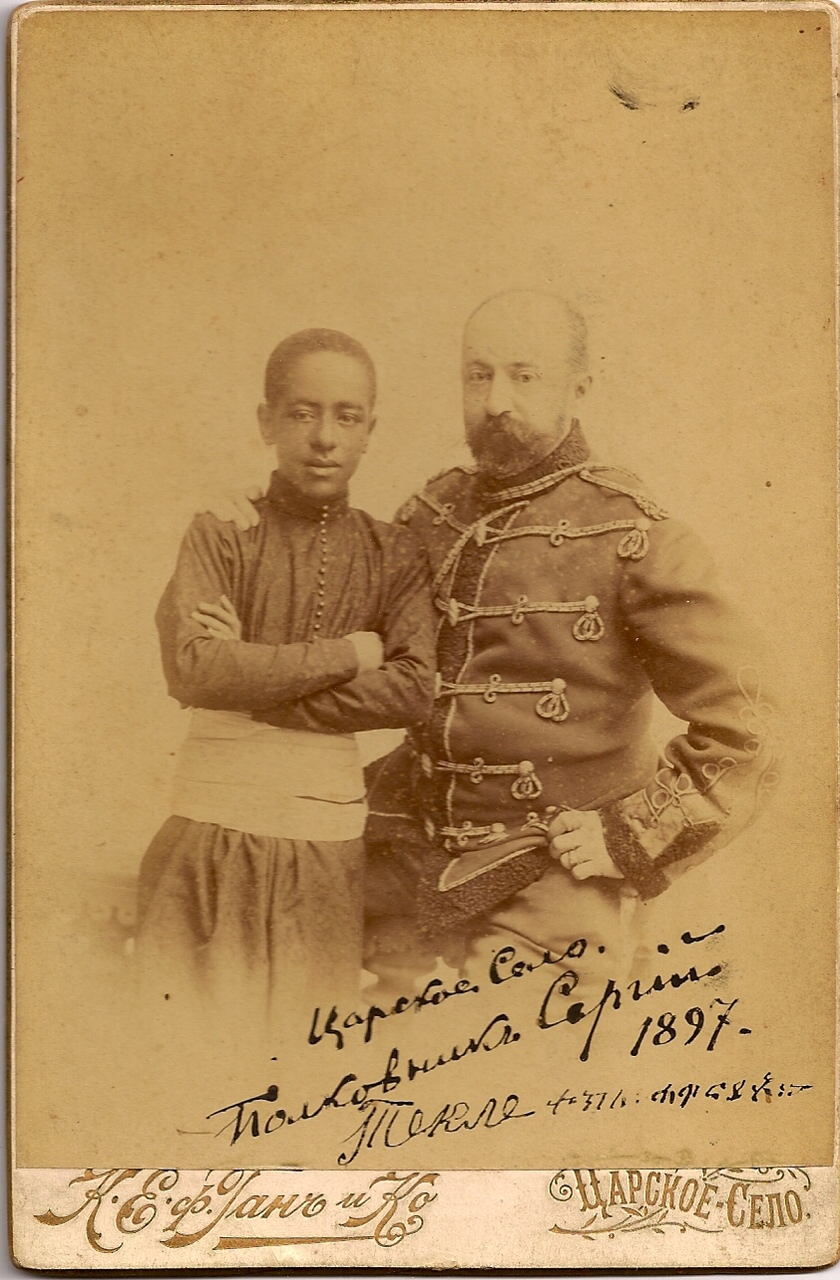

The unlikely pair arrived from Ethiopia after a long voyage by ship to Odessa which was an important port on the Black Sea and one that would be the most logical place for the unlikely pair to debark in Russia. The first destination along Tekle’s Russian journey was likely Veisbakhovka where Molchanov’s mother, Nelly or Babushka as she would come to be called by Tekle lived with her third husband, Alexander Alexeiseivitch Rakhmanov (1830-1911). Eventually, the pair made their way to Sergei’s house near the barracks of his regiment in Tsarskoe Selo were the became somewhat of a celebrity in the Imperial court. In a picture that was taken in 1897 in Tsarskoe Selo, Colonel Sergei can be seen sitting in his Hussar uniform, with his arm loving positioned on his adopted sons shoulders. Standing near him is a serious but relaxed Tekle who is still in his native Abyssian clothes and already exhibiting the pride self-assurance and promise of a thirteen year old boy who is becoming a man. The photograph is signed by both Tekle and Sergei with Tekle’s name in Russian hinting that the writer had only just learnt to spell his name in Russian and adding his last name in Amharic for good measure. There is no doubt that Tekle was made to feel welcome and safe in his adopted father’s mysterious world. Years later, his nephew, Sergei Mikhailovitch Kotchoubey (1896-1960) would recall that his uncle Sergei was a fantastic person and everyone’s favorite uncle. He would ensure that his adopted son would receive the best possible education and as we learn from government archives which are refereced below, it was no easy feat. Sergei took very seriously his new paternal responsibilities to the 13 year old boy and before finding an appropriate military school for the boy, he entrusted the initial education to his mother at Voronki where two of her five Kotchoubey grandchildren were being educated by tutors.

Tekle Hawariat’s birth date is still contested but the most accurate estimate of his birth date is June 1884. According to official records he was born in the Shoa (Shewa) Province of Abyssinia and educated in a church school in its capital of Adids Ababa before eventually being adopted by Molchanov and being sent to Russia to complete his education in late 1896 at the age of twelve. His birth in Shoa was important for a number of reasons not the least that it was alos the birthplace of Emperor Menelik II (born Sahle Maryam) the grandson of Sahle Selassie of Shewa (Shoa). The Kings of Shewa expanded their territory over the course of the 19th century and Menelik II’s arrival on the throne and the consolidation of lands under his rule made Shewa the geographical center of Ethiopia.

As it turns out, the process of enrollment was to become for Molchanov a Byzantine adventure within a Russian labyrinth of bureaucracy which was only resolved by Imperial favor. Tekle studied on his grandmother’s estate of Voronki and by the time he reached the age of 18, the government archives reveal some of the challenges that Tekle’s family faced in getting him into a military academy. In an article by A. P. Piskunova, An Abyssinian’s Education in Russia, (АБИССИНЕЦ НА УЧЕБЕ В РОССИИ. ИЗ ЖИЗНИ ВИДНОГО ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОГО ДЕЯТЕЛЯ ЭФИОПИИ ТЕКЛЕ ХАУАРИАТА) (see: Article on Tekle Hawariat’s Education (in Russian), the author consults oa number of Russian government archives that gives us insight into the preparatory aspects of attending a military academy.

Firstly, it should be noted that according to Piskunova, that the St Petersburg’s First Kadetsky Corpus / Первый кадетский корпус founded by Empress Anna Ionnovna in 1736 was open only to sons of officers, military doctors and candidates who had ties to the teaching staff of military academies. Foreign students needed to find sponsorship directly from members of the Russian Government. The author argues that when Tekle arrived in Russia as a twelve or thirteen year old boy, he would not have been in a position to be accepted or attend a Military Academy as the minimum requirements were knowledge of the Orthodox cathecism, the Russian language and arithmatic. While, it appears that this problem was addressed by the educational oversight of Tekle’s Babushka Nelly on her estate, it remains unclear how the other four Ethiopian students overcame these hurdles. Interestinly, Piskunova mentions Molchanov’s regimental affiliations which are inconsistent with other historical sources and claims that he was part of the officer class of the General Inspectorate of his Imperial Highness’s Cavalry regiment under the command of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaivitch.

We learn from government archives that Tekle entered the 6th class of the First Kadetski Corpus in 1902 at the age of eighteen and a half with the highest sponsorship, which was most likely Emperor Nicholas II. He graduated in 1904. Interestingly, the sponsorship of Tekle’s education was so specific that there is a separate file within the Russian Military Archives and a separate case that was opened to address the request to give Tekle a place at a military academy after the completion of his education within the Kadetski Corpus. On February 12th, 1902, Molchanov submitted an official application to the dean of the Russian Military Academies to request a place for his ward, Tekle Hawariat son of Abai (Molchanov does not use the term “son” but instead a word that stipulates Molchanov as the person who is raising him) at any of the military academies, with the caveat that the candidate does not speak German or have specified knowledge of the Orthodox cathecism. More specifically, Molchanov asks that the dean find a place for Tekle within the Artillery School despite the absence of higher course work in his curriculum. Tekle’s passport and necessary documentation was attached. On Molchanov’s application, there is a handwritten comment addressed to the War Minister, A. N. Kuropatkin from the patron of Russian Military Academies, the Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovitch which gives permission to overlook the absence of the German language and coursework in Orthodoxy due to the fact that the student would be returning to his country after graduation. The request was politely declined by the War Minister who suggested that the student would be better suited transferring to a general class within the school for Junkers.

Molchanov was not deterred by the response although clearly frustrated that even the Imperial patron of the Military Academies could not sway the opinion of the Russian bureaucracy. The School for Junkers was not on the same academic level as the Kadetski Corpus and required an entrance exam. Molchanov would not take no for an answer. This time on behalf of the Emperor Nicholas II, Molchanov applied a second time to 1) to allow Tekle to sit an exam for the 7th class without German or Orthodoxy and 2) following the successful completion of his course of study in the Kadetski Corpus but without any higher coursework to be accepte to the Mikhailovskoe Artillery School / Михайловское Артиллерийское Училище. It should be noted that Mikhailovskoe was one of the most prestigious military academies which exceptionally produced both officers who had their choice of regiments and diplomats. Nikolai Arkadievitch, Sergei deceased step-father had been a graduate of the school as were his brothers. Peter Sergeivitch Tekle Hawariate / Петр Сергеевич Текле-Хавариате as he was officially enrolled at school graduated from the First Kadetskiy Korpus in 1904 and then graduated from Mikhailovskoe in 1907 (see. S Wolkov’s list of Participants of the White Movement in Russia (in Russian)). It appears that the Emperor’s request which was submitted on April 11, 1902 as specified by Molchanov arrived at the desk of the War Minister who acquiesced to the letter if Tekle passed his exams for the 7th class.

The story that unfolds is more interesting for the fierce commitment with which Molchanov shows in fighting for his son’s academic career and one cannot help to wonder what would have happened to Tekle if it were not for Molchanov’s persistance. As it turned out, Tekle was able to advance to class 7 but he was not sufficiently prepared. As a result Molchanov rushed to see Shtalmeister Baron Budberg (see related story about Deputy Prime Minister Nicholass Clegg and his Great Aunt Budberg) who was head of the Imperial Chancellery and to whom Molchanov hoped to express his apologies. Baron Budberg writes to the War Minister Kuropatkin as quoted in A. Piskunova’s article.

“Today, Molchanov ran over to me in a state of deepest distress, because it appears that he had intended to apply for (Tekle) to the 6th class, but received permission for him to attend the 7th class. I suspect there was a misunderstanding and if not I would hope that your excellency will not be against the reversal of this good deed and forgive my intrusion.”

This time Kuropatkin needed to reapproach the Emperor to ask him for permission for Tekle to attend the 6th class and not the 7th as stated in the correspondences from February and April 1902.

The story illustrates the typical Russian blind commitment to the rules unless instructed by a higher authority to bend them. In this case, if the Emperor insisted, the War Minister was only to happy to bend, albeit with some face-saving nuances. Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovitch’s written remarks are also interesting because it gives us some insight into Tekle’s future plans which obviously did not include staying in Russia and further insight into the government’s view of Tekle’s future as a military officer. It suggests, in effect that already in 1902, there were no plans to commission him as an officer in his Imperial Majesty’s armies. Perhaps, this explains that the original mission of sending Tekle and his four Ethiopian companions to Russia was always intended to be a finite journey that would return them all to Ethiopia to serve their Emperor, their people and their country.

The Raven Baron: A Celebrity at the Military Academy:

The enthousiasm for Ethiopia did not wane with the departure of Leontiev and Menelik II’s delegation from St. Petersburg to Ethiopia. Among the seeds of friendship that was left to blossom was that of young Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam (in French and Italian he is referred to as Tecle Hawriate or Havariate) who was known affectionately by his Russian family and friends as Piotr or Petia the Abyssinian / Петя Абиссинский . Russians are traditionally a xenophobic people who are not known for their openness to other races, and yet thanks to the pioneering efforts of General Hannibal in Peter’s time and Alexander Pushkin less than a hundred years before , Russians were in awe of the Abyssinian factor.

In an article written by Col. Erast Erastovitch Shliakhtin / полковник Эраст Эрастович Шляхтин (1886–1973) in the magazine, True War Stores / Военная быль (see: http://lepassemilitaire.ru/mixajlovskoe-artillerijskoe-uchilishhe-polkovnik-shlyaxtin/) , we have a small taste of Tekle, his self-assurance and his life at the school from the eyes of a contemporary writting about events in August 31, 1904.

…Первыми, на кого мы обратили внимание, когда пришли из дежурной комнаты в камеру (так назывался наш дортуар, представлявший собою коридор с несколькими перпендикулярными к нему нишами, в которых были поставлены два ряда кроватей, по 10 в каждой нише) были два кадета петербургских корпусов, прибывших поэтому раньше нас и успевших уже сменить кадетскую форму на повседневную юнкерскую. Один из них, суетившийся и распоряжавшийся, назначенный старшим в нашем отделении, был вице-фельдфебель Антон Мейгардович Шифнер-Маркевич, а попросту — добрейший Антоша Шифнер, окончивший наше училище первым, а в 1913 году вместе со мною и Николаевскую военную академию. Потом он был известен как начальник штаба конного корпуса генерала Шкуро.

Второй был абиссинец Петр Текле Хавариати. Маленького роста, курчавый, шоколадного цвета кожи, с правильными чертами лица и толстыми губами. Он был скромный, застенчивый, добрый, немножко тугодум. Все мы его очень любили. Привезла его какая-то миссия, ездившая в Абиссинию, принадлежал он к аристократическим кругам, близким по родству к самому Царю Царей. В нем приняла большое участие богатая помещичья семья Кочубей, куда он из училища, и очевидно, и из кадетского корпуса ездил в отпуск. Его подготовили и он окончил в Петербурге Первый кадетский корпус. Перед ним, наверно на год раньше, в тот же корпус поступил и другой абиссинец Терье, который вышел в эскадрон Николаевского кавалерийского училища. Нам рассказывали, что наш Текле, встретив в первый раз в корпусе Терье, один только раз прошел с ним по классному корридору и больше никогда с ним не разговаривал, и на вопросы кадет, правда ли, что Терье принадлежит к знатному роду, потому что у него на теле имеется татуировка, с презрением ответил, что у них в Абиссинии клеймят только рабов. У нас в училище в распоряжение каждого отделения придавался служитель, который, помимо других своих обязанностей, следил за порядком в нашей спальне и хранил в особом помещении собственные юнкерские вещи, главным образом самое дорогое наше достояние — лакированные или шагреневые сапоги, художественное произведение лучших мастеров сапожного искусства, Мещанинова, Шевелева и др., а также и отпускное парадное обмундирование. Юнкера платили им особое вознаграждение, служившее подспорьем к получаемому ими жалованью. Эти служителя первое время очень интересовались, остается ли полотенце таким же белым после того, как Текле, умывшись, вытирал свое лицо. Солдаты, которые подавали нам для езды верховых и орудийных лошадей, называли его «вороным» барином.”

The second was the Abyssinian, Piotr Tekle Hawariat / абиссинец Петр Текле Хавариат. He was of small height with curly hair and chocolate coloured skin, with regular facial features and thick lips. He was humble, shy, kind and deliberate in his actions. We all loved him very much. He was brought back by some sort of mission that went to Abyssinia, and he belonged to aristocratic circles and was closely related to the King of Kings, himself. The wealthy landowning Kotchoubey family took great care in him and where, from the school, and before that from the Kadetsky Corpus / кадетской корпус he would go on holiday breaks. They prepared him to the point that he finished the St. Petersburg’s First Kadetskiy Korpus / Петербурге Первый кадетский корпус. A year ahead of him, probably a year earlier, in the same corpus, enrolled another Abyssinian, Tere. He only once walked with him through the school hall and never again spoke with him and when the cadets asked “is it true that Tere belongs to a noble family because on his body there are tattoos?” with contempt he responded, that in Abyssinia they only branded slaves. At the school, in every section we were assigned a servant, who among his other duties, oversaw order in our sleeping quarters and guarded in a specific place the belongings of the junkers -mainly our most precious possesions -laquered or shagreen boots, which were the artistic creations of the finest masters of the bootmaker’s art, Meschaninov / Мещанинов, Schevelev / Шевелев and others, as well as our parade uniforms that we wore on our days out . The junkers supplemented the servants’s pay with additional tips. All the servants were very curious to know at first if the towel would stay as white after Tekle, having washed his face, with dry himself. The soldiers who prepared our horses for riding or artillery excercises called him the Raven Baron / вороный барин…

Tekle, now an eager chronicler of his life in Russia and most likely with a camera in hand, took time to capture the funeral on his camera. Sergei had died on the ninth of May, 1905 and now it was the end of May and the leaves had already long emerged from their winter slumber and the warm summer son was shining. As per protocal, the family assembled at the train station to receive the funeral train. In a separate wagon adored by red carnations in the sign of the cross, lay the body of Sergei in his lead lined, flag drapped coffin. On the station platform, the young Kotchoubey boys in their summer linen sailor suits looked anxiously at their father, mother, grandmother and aunts who stood their with members of the local clergy, gentry and estate workers to pray for Sergei’s eternal repose and to bury him near the newly built chapel where his Volkonsk grandparents, Alexander Poggio and his wife and his step-father Nikolai Kotchoubey had been laid to rest.

Hundreds of people had come to the station to pay hommage to Sergei and soldiers were resplendent in their summer whites, priests were wearing their golden vestments and the cossacks and locals were wearing their clean starched shirts with their belts pulled tied around their waste in the Ukrainian style. Nelly’s carriage was reconfigured to carry the coffin and a team of four black horses were hitched to the carriage to carry the coffin to the newly built church on the estate. As the cortege wound through the village from the station to the church, the choir sang the melancholic funeral dirge of the Orthodox church and at church the congregation kneeled as the choir sang “Eternal Memory”. The towns people carried the church lanterns and it seemed like 50 clergy marched solemnly in the funeral procession. The servants accompanying the cortege were dressed in black and their proud beards were tamed into elegant marks of seniority with their mustaches curled into salute.

After the church service, the family and a few close members of the estate family wound their way up the hill towards Sergei’s final resting place. At every moment, Tekle patiently set up his camera and took pictures of the funeral. It was as if he was frantically trying to capture every mement so that in the future he could carry the memory of his father’s funeral with him whereever he went. Sergei, the father of Russia’s most renowned Abyssinian in the 20th century was laid to rest next to his grandmother, Maria Nikolaievna, the object of Russia greatest poet’s affection, Alexander Pushkin a descendent of an Abyssinian.

With the funeral behind him, Tekle received news from the family lawyers that he was heir to his father’s estate. With two more years before he would graduate from the academy it was time to think about the future, one that was made possible now by funds that were now his to spend with the guidance of his grandmother, Nelly. The news was hardly comforting in the face of Tekle’s sorrow but more worringly, the countryside in Malorussia had turned violent and Tekle was witness to the growing disillusionment of the Russian people in the capital as well as the countryside.

Without an officer’s commission to keep him in Russia and with the funds he inherited from Sergei Molchanov, Tekle decided to leave St. Petersburg in 1907 and tour Great Britain, Fance and of course Italy where the Volkonsky family were frequent visitors. In 1908, he returned back to his native Ethiopia and while photographs suggest that he may have returned to visit his family in Russia after that date, it is most likely that the next time he saw a member of his Russian family was his tante Helene in Paris many years later.

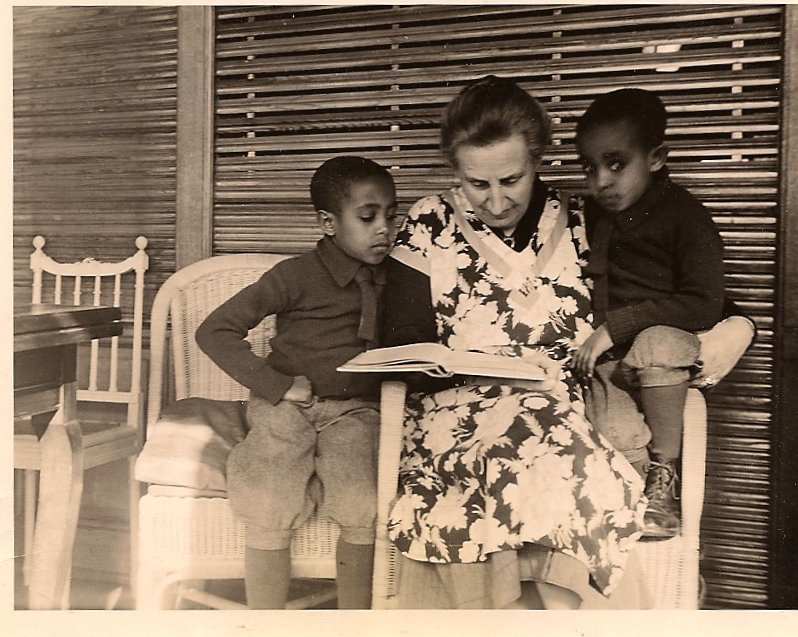

The family sitaution for the Kotchoubeys-Volkonskys was less than ideal and his grandmother Nelly suffered a dibilitating stroke after arguing with her son, Mikhail regarding family matters in 1909. At that point Mikhail decided to leave his children and his family and moved to St. Petersburg with his school teacher girl friend. The remained in the capital for a few years anf then in 1913 moved to France. Nelly had aged dramatically in those last years and she was now wheel chair bound. She was using the same wheel chair that her father had used before her and photographs in Tekle’s album captured some wonderful moments of his grandmother at home, hosting her guests around a huge table. In other photographs a whole cossack detachment is pictured in all their chaotic glory, surrounding the slight image of Babushka Nelly in her wheelchair. Tekle last saw his grandmother in 1908 because that was the year he decided to leave Russia and return for the first time to his native Ethiopia.

Returning to Ethiopia was a realization of a dream that Ras makonnen had for the select few Ethiopians who were sent to Russia to be educated. Tekle’s return was not only part of the plan but his new responsibilities quickly launched him into the tumultuous but progressive development of Ethiopia as a European inspired north African Empire State. In the vanguard of this transformation were the educated elite among whom was young Tekle. A short biography of Tekle’s various roles before the invasion of Italy in 1835 include being head of the Adis Ababa municipality, a comptroller of the Ababa-Djibouti Railway in 1915 and accompanying a British exploration team to lake Tana. In 1915, the first of his eight children was born, Germachew Tekle Hawariat (1915, Hirna-1987, Harahrghe) who would become a novelist and playwright as well as a member of the Ethiopian government and would play an important role in the narrative of his father’s lost photo album. From 1958.1960 he was the Ethiopian ambassador to Italy. In 1917 he was appointed as governor of Jijiga where he transformed the outpost town into a modern funcitioning municipality. He was then made governor of western Harar’s Chercher province which he governed for seven years. A new capital was established in Asabe Teferi and through various reforms and a clear emphasis on development, the region began to grow. From his farm in Hirna which is near Asabe Teferi in the western part of modern day Hararhge in the Chercher Mountains along an ancient caravan route, he would build his home but be forced to flee over the border to Djibouti after the Italian invasion. From there he tried to organize relief efforts for Ethiopian refugees, but his presence was considered politically explosive for the British government and he was never granted permission to reside there.

The annointed son’s trajectory to leadership was temporarily disrupted when Ras Tafari (the future Emperor Haile Selassie) imprisoned him briefly in Adis Ababa but by 1930 he was tasked with writing Ethiopia’s first constitution which was based on the Japanese Meiji constitution and would remain in place from 1934-1955.

A Russian Estate in Ethiopia:

It is diffiuclt to imagine that having spent his formative years in Russia, that he would not be directly or subconsciously influenced by the many aspects of Russian life that he confronted in his thirteen years in St. Petersburg and on the family estate. As was the case for him growing up in Adis Ababa, Tekle was being raised in the cradle of power and influence. While the experiences in St. Petersburg would give him a first rate military education and a chance to live within a world of privilege and service, life on the country estate was a in sharp contrast to this world.

When Tekle arrived in Voronki in 1897, the estate along with Veisbakhovka where his grandmother Nelly lived were not only economic centers of agricultural enterprises but centers of theater and the arts. For Tekle, the chance to witness a the operations of a working Ukrainain estate was unrivaled in its production capacity in Russia at the time. Traditionally, ukraine was known as the breadbasket of Russian if not Europe and on the eve of WWI, the region accounted for nearly 66% of Russia’s grain export production. The wealth generation in inconjunction with the coal and iron works in the Donbass, made Ukraine the economic heart of Russia. Only ten years ealrier in 1886, Nelly and her third husband Alexander had completed the construction of an ensemble of buildings that would bring a neo-Russian-Ukrainian revival of 18th century architectural styles to a magnificant main house and two flegels (separate wings to the main house) that incorporated fruit orchards, various buildings for the laundry, kitchen and estate management as well as several beautiful parks, all of which were laid out according to a pre-determined plan. In Voronki, the more humble buildings were certainly impressive in comparison with the traditional Ukrainian Khutors (peasant houses) that lined the central streets of both villages but where Veisbakhovka was a study in architectural follies, Voronki was a tribute to the performing arts with its renowned theater and musical traditions. These were established by the Volkonskys on the Kotchoubey estate upon their arrival from Irkutsk Siberia in the late 1850s and would form the core of a theatrical and academic foundation to life on this country estate.

For Tekle, these experiences would manifest themselves in his life both in Ethiopia and abroad as he would take from his Russian years a basis of reference for government and military affairs as well as an appreciation for the administration of country estates or farms as well as the highest of human endeavors in the performing arts, albeit on a more country scale.

of At this juncture in the story, it is relevant to mention that Tekle’s Russian roots would guide him in his vision for the various farms and agricultural enterprises that he would oversee. Some were successful and others such as his farm in Madagascar where he fled from Djibouti after falling out with the Ethiopian government in exile and Haile Selassie about the war with Italy was less successful. Up until an Italian General occupied his home, he would take with him his extensive library which contained books many books in Russian, French, Amharic and English.

When designing and running his various farms, he borrowed heavily from what he experienced on the Russian estate of his grandmother Nelly at Veisbakhovka and his Kotchoubey cousins at Voronki. In his photo album, there are careful notes on the various buildings and their role as well as estensive photographs of the park and the interior of his grandmother’s neo-Russian revival palace which was designed by the renowned architect Yagn and his interior designer Sokolov. His farm in Hirna in modern day Hararge province to which he would return from exile from Madagascar in 1955 after reconciling with Emperor Haile Selassie was a showcase for different farming techniques.

It was from his farm in Hirna, that Tekle Hawariat and his young family would flee following the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1835. Denied permission to remain in Djibouti, the family moved to France but in an echo to many of his adopted cousins and aunts in Russia who less than fifteen years before fled to Bulgaria and Italy, Tekle was forced to leave his homeland angain and this tme without his treasured possessions and memories of Russia.

Unbeknownst to the exiled family, an Italian General occupied Tekle’s home and found himself in a european style home with all the comforts of a landed gentleman. In the course of the Italian withdrawal many years later, the General decided to return to Italy with the contents of the house. A small token of war booty for the years of hardship that the Italian seemingly endured during the occupation.

A lost history returned.

It seemed to Tekle’s son, Germachew that 1935 was a world away. Now the Ethiopian ambassador to Italy in 1958 and in the midst of the many important government roles that he would play and for which he played a high price by being improsed both in Italy and in Ethiopia twice in his life, he was none the less a tireless advocate for his country as was Tekle who pre-deceased his son by only ten years.

One day, Ambassador Germachew Tekle Hawariat received an unexpected visist from a retired Italian general. The visist to the embassy was more remarkable in that accompanying the retired general was a truckload or books, photoalbums and household items that were being returned to the Ambassador as it was taken from the house in Hirna which the old general had occupied many years before. Despite years of dislocation and the pain endured from having family archives stolen, the Ambassador was reunited with his father’s affects and it was small victory for what had been a long journey from the family’s beloved home in Chercher.

Tekle’s children and family would learn much about him through the many items that returned to the family but sadly time and emigration meant that ties with the Russian family were lost. Tekle’s beloved tante Helene died in Florence in 1946 although she was present during the Ambassador’s visits to France as well as his life in Ethiopia as a child. Nonetheless, all that would become a faded memory that was captured in a wonderful photo album which had been with Tekle since his departure from Russia in 1908.

A True Thanksgiving Reunion:

Thanksgiving dinners outside the United States suffer from a disticnt lack of context and sense of communal celebration. For those who have never been part of this American tradition, it offers a quanit view of some peculiar American traditions that borrow heavily from the traditional English Christmas Turkey and infuse it with a particular American twist. Along with the Turkey that has been basted and prepared in the oven under low heat, the trimmings, as they are called, can include mashed potatoes, candied sweat potatoes, green beans, caramelized onions, turkey stuffing and the all important corn bread muffins.

These feasts of Thanksgiving are a tradition that are not geographically bound. By 2009, Alexander Andreivitch and his family had relocated to Geneva Switzerland. The family gathered in November with a group of friends, many of whom had American ties and all of whom have an appreciation for the meal that awaited them on that cold blustery November day. Among the many guests was Alexander’s father Andrei Sergeivitch and Weynabeba “Weyn” Abate, an Ethiopian by birth and a childhood friend of Alexander’s wife, Anna in Geneva. Andrew was seated next to Weyn who was immediately drawn into an explanation that Andrei’s father had a first cousin who was Ethiopian.

The meal ended with a walk in the forest near the house and as the guests departed, Weyn promised Andrei that on her visit to Addis Ababa the following week, she would ask her father if he knew any members of the family in an effort to get the necessary contact details.

Not only did Weyn’s father know the family but it turned out that Tekle’s granddaughter was visiting from New York that week and Weyn immediately made contact with her. What follwoed was a Shakespearean twist of irony that even the famed bard could have written but it turned out that Andrei Sergeivitch who had been looking for his Ethiopian relatives lived only a 10 minute taxi ride from Tekle’s granddaughter’s apartment in New York City.

On January 13, 2010, Andrei wrote to his newly discovered relative, a granddaughter of Tekle’s who lives in NYC:

Dear Bella,

Dear Mr. Kotchoubey,

My name is Almaz. I am the 7th daughter of Tekle Hawariat. My father had 8 children out of whom only three ( my brother, my sister and myself) are surviving. The other five, two girls and three boys are gone. Four of them have children living in the United States.

I also have a son living in Maryland and working in Washington D.C. He is a Lawyer.

It was indeed a surprise and a joy to learn that Bella, my niece, has established contact with you.

Everybody in the family knows that my father was brought up in Ukrain, during Tsarist Russia, by a family whom he cherished a lot.

I also had the good fortune of living in Russia for four years 1962-1966 during the Soviet regime. I could speak, write and read Russian very well at the time but have forgotten almost all of it now.

We will talk more about all this once we have established contact.

I am really happy and look forward to corresponding with you and your sister.

Amidst the email correspondences between the Russian and Ethiopian sides of the family, a small moment of family history was further enlarged when it was revealed that the family had Tekle’s Russian photo albums and for the first time since flleing Russia at the turn of the 20th century, Tekle’s Russian family was able to see photographs of life on the estate, the interiors of Nelly Volkonsky’s house at Veisbakhovka.

Fitawrari Tekle Hawariyat Tekle Mariam Autobiography: http://www.mereb.com.et/rs/?mpid=40009349