(b. Voronki, Chernigov Province, Russian Empire (possibly Kiev) (15 April 1896 – d. New York, NY, USA 25 December 1960)*

Heir to a Decembrists’ Legacy

What did Sergei’s father know about the fate of the Russian Empire that made him flaunt the rules set forth for members of the nobility or in contradiction to this behaviour led him to follow some of the expected conventions around service while engaging in numerous affairs, fathering children indiscriminately and eventually deciding to sell off his estates, undermine the local economy near his estates by renting his lands to the local peasants at cut-rate prices? Despite, the latent affections that my grandfather, Sergei Mikhailovitch, had for his father, Mikhail Nikolaievitch, he was a man who at once was generous to a fault and ensured the financial stability of his loved ones while at the same time abandoning the women in his life as well as the many legitimate and illegitimate children that he fathered. He lived unconventionally, richly and selfishly and yet his actions were somehow prescient in that the social order that he so vehemently seemed to despise ended on October 25th, 1917 and the Empire that he abandoned around 1912 ceased to exist by 1921. Miraculously, his Kotchoubey children survived the Revolution but not all of them survived the Civil War. His children and the descendants who carried his name would have to live with the consequences of his action but not all suffered the same fate as at least one set of grandchildren, his eldest two, may have very well survived a life in the Soviet Union thanks to his behaviour and their far reaching consequences.

When I set out to learn about my grandfather and my great grandfather, it was largely to learn truths about my family and their triumphs and traumas as well as the origins of their legacy. Instead, I uncovered a deeper more conflicted past that at once thumbed its nose at the social system that had been created by the Tsar Peter I and that had condemned various members of the family’s illustrious ancestry to unrivalled status while others to the ranks of serfs and back to nobility. It is precisely this history and Mikhail Nikolaievitch’s response to its rules and regulations into which my grandfather, Sergei and his siblings was born,

Were the failures of Sergei’s ancestors to reform Russia in the early 19th century a foreshadowing of the fate that awaited Sergei and his siblings who would all flee Russia and perish far away from their beloved home of Voronki ?

By the end of the nineteenth century, Imperial Russia was lurching into the final decades of its catastrophic demise. Many years before his birth. Sergei’s ancestors, espoused strong liberal views and as such were at odds with the seemingly immovable conservative monarchy which they served. They would try in vain to change the direction of their beloved Russia. As a testament to that legacy, Sergei was christened a few weeks after his birth in the family’s wooden church where his Decembrist great grandparents had been laid to rest. Their graves, on a Kotchoubey estate in Little Russia was a reminder to history that Russia could take what it had given. Sergei’s great Grandfather, born a Prince with a vast fortune, was buried without his title and stripped of all of his estates. It was as if his tomb was a warning to the baby and his brothers and sister that years earlier, in 1825, their great-grandfather had tried to bring modernity to Russia but despite his best efforts and that of a whole generation of enlightened elite, neither he nor they could change Russia’s terrible fate.

In the early spring of 1896, when the vast fields near Voronki are swollen with the waters from the melting winter snows and the puddles in the fields glisten with the April sun dancing in these pools of promise, Sergei Mikhailovitch / Сергей Михайлович (stage name Italy: Sergio Cocciubei) was born. He came into the world and joined a very colorful and unique family. His paternal grandmother was married four times, his uncle adopted an Abyssinian boy and his parents were never married in a church.

His father, a philanthropist, playwright, actor and heir to a small fortune, was Mikhail Nikolaievitch / Михаил Николаевич (1863-1935) and he had long ago fallen for the charms of a beautiful village girl, Pelegea Dmitrievna Onoshko / Пелагея Дмитрьевна Онощко (1863-19.12.1930) who despite her ambiguous origins was as determined and strong willed as she was beautiful. The Onoshko’s who lived in Voronki may have been descendants of the same Onoshko’s who were members of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility. Whatever, the truth, Mikhail Nikolaievitch’s mother, Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna Molchanova-Kotchoubey-Rakhmanova (née Princess Volkonskaya) would have nothing of this potential connection and was not impressed with her son’s particular choice of love interest as she was beneath him in social status. Nonetheless, together the couple had five children. Sergei’s parents were at once a source of inspiration and strength and at the same time a source of disappointment and shame. Despite the many trials that lay ahead for him, his parents probably gave him the means to survive the upheavals in his life and ultimately raise a family in emigration and give them all the traditions and values that he himself was given as a member of the storied noble Kotchoubey family.

Seeking insights so many years later, it is still difficult to know how Sergei’s mother influenced him. Very little is known about her. Despite the fact that Sergei’s father was an accomplished photographer, only two photographs exist of Pelagea. When asked Sergei would explain that the absence of photographs was simply because she did not like to be photographed. In the red corner of his home where the family icons stood, Sergei kept a small photograph of a lady in local costume seated in the doorway of a Khata. She looks out with a hint of bemusement. She is cradling a baby as another woman is standing in the doorway in local dress and looks out into the distance. So personal was Sergei’s relationship with his mother and so guarded was her identity, that many years later when his teenage son noticed the photograph for the first time, he did not know that it was a picture of his grandmother. For most of her life, Pelagea was illiterate but she never accepted that life’s obstacles were insurmountable and in the last years of her life she learned to read and write alongside her granddaughter while living in the same small Kiev apartment in the new socialist paradise that was known as the USSR. Moreover, despite having no formal education or experience, together with her sons and a son-in-law, she took over the management of the family’s bankrupted estate and tirelessly worked to make it viable again. The year she paid the loan back to the bank, Russia found itself in the first convulsions of revolution. It was 1917. These anecdotal episodes point to a humble woman of indomitable strength and a true matriarch in the cossack tradition.

Sergei would fondly remember his father who lavished upon him and his siblings affection and gifts whenever he saw them. His generosity was well known during his own lifetime. Even today, despite years of Soviet rule and the ravages exacted on the countryside from the invading German army and the passage of time, a group of historians and anthropologists from the Museum Complex of the Hetmanate Capital in Baturin made a startling discovery in a little village in rural Ukraine. In Kinoshevka the curators found a faded photograph of Sergei’s father, Mikhail surrounded by local peasant girls. These were girls who were studying in a school that he had opened on their behalf. This was only one such example of a man who gave selflessly to numerous institutions of learning in the region. So to say that Mikhail was generous was an understatement. In fact he was so generous that one may be inclined to conclude that his incredible generosity contributed to the demise of the family fortune. To Sergei, his father’s largesse and love meant that his childhood would be blessed by want for nothing. All this would come at a price, for when Sergei was still a teenager, he was confronted with the terrible fact that his father had abandoned the family (and Russia). Years after the civil unrest in Ukraine from 1905-07, Mikhil left for St. Petersburg in 1909. In1913, he departed for France with his mistress, a school teacher from the village of Voronki. Years later he would die on the Cote d’Azur in 1935, never seeing his family again from the moment he left Russia in 1913.

Voronki / Вороньки, the estate where Sergei was born, first belonged to his grandparents, Nikolai Arkadievitch / Николай Аркадьевич (1827 -1865) and Elena Sergeievna Molchanova Kotchoubey Rakhmanova (née Princess Volkonskaya) / Елена Сергеевна Волконская (Молчанова, Кочубей, Рахманова) (1835 -1916). It is located in the southern part of the Tchernigov province / Черниговская область which is north of Kiev and is found in today in the Bobrovitskiy Region still as it was in Sergei’s time on the banks of the Supoi river. Despite the many years that have passed, it is renowned for its unspoiled beauty and incredible nature. As of 1782, the property belonged to the Miloradovich family who had married into the Kotchoubey family in the early 18th century. It was purchased by Arkadi Vassilievitch / Аркадий Васильевич (1790 -1878) for his son Nikolai in 1850, the year that he handed his eldest son, Piotr Arkadievitch (1825-1897) the management of the family seat at Zgurovka. Voronki’s topography is characterized by vast plains punctuated by stands of pine trees which are separated by meandering rivers and beautiful lakes. Its historical significance today is largely due to the facts that not only the Kotchoubey’s lived there but the fact that the Decembrist, Prince Sergei Grigorovich Volkonsky / Сергей Григорьевич Волконский (1788 -1865) and his wife, Princess Maria Nikolaivna (née Raevskaya) / Мария Николаевна Раевская (Волконская) (1805 -1863) both died and were buried on the estate. Today, there is a commemorative monument, which was erected in 1975 to mark their burial place and that of their fellow exiled Decembrist, Alexander Poggio. The original chapel designed by Alexander Yagn and built in 1905 on the location where Sergei was christened in the original family church was destroyed along with all the family tombs in the 20th century.

Prior to 1917, the region was known as Malorossia or Little Russia. Today it is Ukraine. For 400 years, it was part of a fluid geographic zone that at various times was fought over by the Poles, Lithuanians, Swedes, Ottomans, Russians and Tatars with a group of independent peoples loosely united under a shared identity known as the Zaporozhian Cossacks. They ultimately won independence for themselves from the Lithuanian princes in 1654 and allied themselves to the Russian Tsars but this political exercise lasted for only 100 years until Catherine the Great crushed their capital, Baturyn and dissolved their autonomy by folding the Hetmanate state permanently into the Russian Imperial administrative apparatus. Throughout, this period the Kotchoubeys played an active role in the fortunes of their adopted homeland. The first Kotchoubeys to arrive in the region in the early 17th c. settled in and around Poltava which was an important region for both cossacks and Tatars. Once firmly in the leadership structure of the Hetmanate state, the family’s property holdings expanded north to include important villages in Tchernigov as well as further south around the ancient city of Kiev. The family was constantly reinventing itself having served the Khans of Crimea as Princes of the blood / murzas, then after the 17th century the Hetmans as their comrades-in-arms and finally the Tsars as their ministers, chancellors and govermors.

Early Childhood: From the forests of Chernigov to Capital cities of the Russian Empire.

Sergei was the youngest of four brothers, Vassili, Nikolai, Mikhail & Sergei and one sister, Elena “Nelly.” Sergei’s lifelong love of music and theater was influenced by his father, Mikhail Nikolaievitch’s theatre located on the Voronki estate and his theatrical productions as well as the plays that he wrote both in Russian and Ukrainian. Despite his inclinations for the arts, Sergei was educated at home or the village school until he was first sent to Kyiv to study at the Second Kiev Gymnsaium. Eventually, he would follow his older brothers to St. Petersburg to study at the Nikolaevskiy Kadetskiy Corpus (Николаевский кадетский корпус) located at 23 Ofitserskaya Ulitsa but the date of his enrollment is unclear even if he graduated in 1914. It was one of the many pre-Revolutionary addresses that Sergei would keep safely stowed away in his memory throughout his life. The Kadets was a military preparatory school for future cavalry officers and not more or less comfortable than other similar schools. Perhaps Sergei benefited from the presence of his older brothers.

Sergei would remember that until his father abandoned the family, he behaved like a devoted father who showered Sergei and his siblings with affection and gifts whenever he saw them. These sweet memories and that of his father’s car getting stuck on the road and being pulled out by oxen were recounted when talk turned to the past years later when Sergei lived in emigration. His favourite book from childhood was Taras Bulba by Nikolai Gogol. This was quite an ironic book for Sergei to love as it told of the glories of the Zaporozhian cossacks and the tragedy of a son’s betrayal for the love of a woman which played out in reverse fashion with Sergei’s father betraying his sons by running away with another woman and dismissing conventions expected of a hereditary nobleman. Another perhaps more obvious connection was that the book was written by an author who came from Poltava and grew up in Dikanka in the shadows of one of the most famous Kotchoubey estates of the same name.

Another memory which seems at odds with the limitations that Mikhailo put on his Kotchoubey children when Sergei vividly recounted to his own children how he remembered the moment when Emperor Nicholas II came to visit the Nikolaevsky Kadet’s school and during an informal moment, upon learning that the young cadet in front of him was a Kotchoubey, the Emperor who only reached 1m70 in height lifted young Sergei in his arms and asked,

“why are you so small when the rest of your brothers are so tall?”

The children of Mikhail Nikolaievitch Kotchoubey stayed near their mother who lived on the Kotchoubey estate of Voronki and their grandmother Nelly Rakhmanova (née Princess Vokonskaya) who lived in near by Veisbokhovka in near Prilukiy. Even if at the time of Sergei’s schooling in St. Petersburg, there were many members of the family at Nicholas II’s court, it’s not clear whether they even saw the young boys or looked on the with resigned pity because of their father’s behaviour. Sergei’s distant aunt, Princess Elena Konstantinovna (née Beloselsky-Belozersky) (Елена Константиновна Белосельская-Белозерская (Кочубей) (1869-1944) was a lady in waiting to the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna before she married her husband Lt. General Prince Sergei Viktorovitch (Виктор Сергеевич) (1860-1923). He was a close friend and an aide-de-camp to Nicholas II and accompanied him on to tour of Asia including Japan when Grand Duke Nicholas was still Tsarevitch. Prince Sergei and his wife, were the last owners of the famed Dikanka palace in Poltava. Yet another uncle, Vassili Petrovich, a Guard’s officer was to be named Master of Ceremonies & Kamer-Junker (камер юнкер) of the Imperial Court in 1912.

The family was well off and Sergei was quick to point out that when he was young he never had or needed cash. He lived on a very convenient system of credit that was extended to him by the status he held as the son of Mikhail Nikolaivitch. Whenever he incurred an expense he would just say who he was and his father would be billed.The local bank was jokingly known as the Kotchoubeievsky bank because there were instances when the same invoices were paid multiple times. It appeared that Sergei’s father did not practice strict accounting controls. After Mikhail left his family and his estate, the bank was moving to repossess the house but Pelageia Dmitrieva, Sergei’s mother, convinced the bank to give her a mortgage and she took over the management of the estate and was an excellent estate manager.

The Voluntary Army under Gen. Anton Denikin

Unlike two of his older brothers who went to the Elisabetgradskoe Cavalerskoe Uchileshe (Елисаветградское кавалерийское училище), Sergei graduated from the Kadets but it is unclear what he did between 1914 and 1918 when he got married and then joined the Volunteer army. Two of Sergei’s elder brothers, Vassili* and Nikolai both served in the 11th Izumskiy Hussar regiment of his Royal Highness Prince Henry of Prussia (11-й гусарский Изюмский Его Королевского Высочества Принца Генриха Прусского полк) and another brother, Mikhail went to study law at the University of Kyiv. Sergei’s only known resumé was a heavily edited page written in pencil that purposefully misled the reader by stating that he was born in 1899 and graduated from the Kadets in 1917, This was done to appear younger to potential employers in the United States but was incorrect. There is a recored of a Sergei Kotchoubey graduating from the Alexandrovsky War Institute in 1917 but as neither Sergei nor his CV allude to having studied there, it is probably not the same Sergei. The story goes that he did not receive a commission as an officer because 1) he received no further instructions or schooling after leaving the Kadets and 2) protocol required that at least one brother remain out of harm’s way. With his father in Europe and no longer in touch with his Kotchoubey children, it appeared that Sergei returned to the family’s estate, Voronki far from the tumultuous events on the Front to live with his mother and his sister-in-law Ludmilla Alexandrovna Kotchoubey (née Podust) who was married to Vassili and who had given birth to their daughter Olga Vassilievna in 1911 and then their son Georgi Vassilievitch “George” in 1915. In addition, Sergei must have also helped his mother manage the income from the estates along with his brother-in-law Dmitri Axelievitch Wickberg (married to Elena “Nelly” Mikhailovna) run the family properties. He would have certainly visited his grandmother, princess Elena Sergeievna at her estate in Veisbokhovka. She lived their and died in the last days of 1916.

*Vassili joined the 10th Ingelmanlandskiy 10th Hussar Regiment (10- го гусарского полка) at the begining of 1917.

Before emigrating to Europe, Mikhail Nikolaievitch had done quite a lot in favor of the pesants living on his various estate. Specifically in Voronki after the 1905 Revolution, he began to rent out his land to the pesants at an annual rent of 6 rubles per desyatin (vs. the normal rate of 18 rubles) and of course he was a benefactor in otther ways, having built a brick church and a local school. As a result, it is not clear how the local peasants or the Bolshevik agitators viewed the Kotchoubey family. Nonetheless, Voronki would not have escaped the upheavals in the various other parts of European Russia. It may have been a microcosm of the broader breakdown in social order in Russia following the abdication of the Tsar and the chaos that ensued with the Provisional government’s inability to take control and the devastating losses on the Front. The horrors of Bolshevism was brought home to the quiet countryside, when members of the Red faction arrived. Sergei Mikhailovitch never spoke of this event but his brother Mikhail Mikhailovitch would recount in Paris in 1961, how the Bolshevik agitators wreaked havoc on the family and one group of brigands even entered their father’s half-sister’s apartment late one night after a gathering of friends and raped her in Prilukiy.

With the collapse of social order and their idyllic world crashing about them, it was not too difficult to imagine the motivation for doing the Voluntary Army. Across Russia, regiments still loyal to the Tsar or the Provisional government were unifying under the command of various army leaders. At the beginning of 1918, officers and members of the disbanded Izumskiy Hussars, which had ceased to exist in October 1917, reformed their ranks under the command of the Hetman Skoropadskiy and was renanmed the Ukrainian 9th Iziumskiy Cavalry regiment and in September 1918, General Anton Denikin, personally received the old standard of the Hussar regiment and it officially came under his command. Sergei along with his brothers had now joined the Voluntary Army. It was November 1918. The brothers were put to work in the intelligence operations of the White Army and served in the OSVAG (office of the Russian Press). They were involved in highly classified missions throughout 1919.

At one point, when Denikin’s army was firmly in control of Ukraine, Sergei returned to visit his elderly mother and to his beloved Voronki. The story would have been played out across Russia with similar acts of hooliganism on estates, and Voronki’s situation was no different as Sergei found his home ransacked and pillaged. The local peasants who had already began to defy the landowners during the 1905-1907 uprising, arrived to young Sergei dressed in his drab olive officers uniform and addressing him as Pan, excused themselves, saying that they were forced to steal the family’s possessions. The use of the honorific Pan, a now obsolete form of address which is similar to Sir or Sudar in Russian may have been intended to be a respectful form of address which was used in Ukraine & Poland but there are examples where this form of address was meant to be condescending. Many of the people who had toiled in the fields and worked on the estate came forward to start returning the stolen goods but this was war and Sergei was due back to headquarters. There was little to be done at that point. When it would all be over, Sergei would return and sort it out but at least his last memory of Voronki was a reminder of the love and the respect that the people had for the family. Soon after his departure, Voronki would fall back into the hands of the Bolsheviks.

Following Denikin’s defeat in 1919 and his retreat to Crimea, Sergei and his brothers would serve under General Pyotr Wrangel. It was not war all the time and in the lulls in activity, Sergei married Evgenia Viktorovna Yankovskaya in 1919. The marriage, which lasted until 1929 was childless but wrought with extraordinary moments. Many years later, Sergei, nonetheless, looked back on his first marriage and dismissed it as a folly of youth. As a young soldier in the Voluntary Army, in the midst of a bloody Civil War it seemed that everyone around him was getting married. His brother, Michael would marry Evgenia’s sister Olga in the same year. They say that the impulse to love and to embrace ones humanity comes even when we witness the dark moments of man’s cruelty and in the times we feel the most despair. It’s the triumph of goodness over evil. Months after their marriage, news came that the war effort was lost and the couple along with Sergei’s brothers and their wives moved further south to Sevastopol where in November 1920 they all went aboard a ship which was part of the remaining Russian Imperial fleet, and became known as the infamous Wrangel fleet. With the rest of the fleeing White army, Sergei and his wife traveled briefly to Constantinople, but tragically his eldest brother Vassili was lost at sea and died. In 1921, he traveled to Sofia, Bulgaria with his brothers Nicholas & Michael and their wives, Evgenia, Olga and Nikolai’s wife Sofia Alexandrovna Grabovskaya.

A new Chapter: Sophia Bulgaria

A thriving White Russian community emerged in Sofia in the 1920s and the three remaining brothers, started to rebuild their lives in emigration. Michael & Sergei who were both married to two sisters (Olga & Evgenia Mankovsky) set up in Sofia. Sergei found work at the Greek-Bulgarian Commission of the Legation of League of Nations. For Sergei, the city of Sofia was not a happy place. It had become marred by the death of yet another brother, Nicholas, in 1924 and then a failed marriage. Up until the early 1930s, Sergei did not lose hope that he would return to his native Russia and perhaps be reunited with his mother, sister, sister-in-law and the lands that he loved.

One particulary poignant moment was during a visit to Paris to see his brother, Mikhail in the late 1920s. The brothers were strolling in the city center when they saw in the window of a passing tram their father seated in the back. Sergei, having last seen his father in 1909, reacted spontaneously by preparing to rush after the tram and climb aboard at the next stop to embrace his father. It is hard to imagine how he felt after so much time had passed and after all the tragedy that the family had endured. Here he was in Paris in the roaring ’20s and suddenly he sees his father, an all to familiar face staring from the window. Before Sergei could run, Mikhail placed his hand on his arms to restrain Sergei and stated sternly, “Do not dare approach him for he is dead to us. After what he did to us and our mother, after he abandoned us, he does not deserve to have sons. ” Sergei hesitated and in those brief moments the tram pulled away too far for either of them to catch up to it. Did their father see them? It was of little matter. No one in the family would ever see him again.

Back in Bulgaria, through his comrades-in-arms and thanks to his musical talent, he was accepted into the General Platoff Don Cossack Chorus under the direction of Nicholas Kostrukoff in 1928 where he found fellow Russian émigrés, a shared love of Russian musical culture, and a new purpose. While his last remaining brother, Michael left for Paris, Sergei, newly single, left Bulgaria and traveled throughout Europe keeping alive the singing and dancing traditions of the cossacks and secretly holding on to the hope of returning back to his native lands.

He traveled with the chorus all over Europe and North Africa but refused to travel further with the troop to South America or Asia in case the Bolshevik government fell.

Sergei pictured in the opening scene as the Cossack Chorus arrives in Amsterdam.

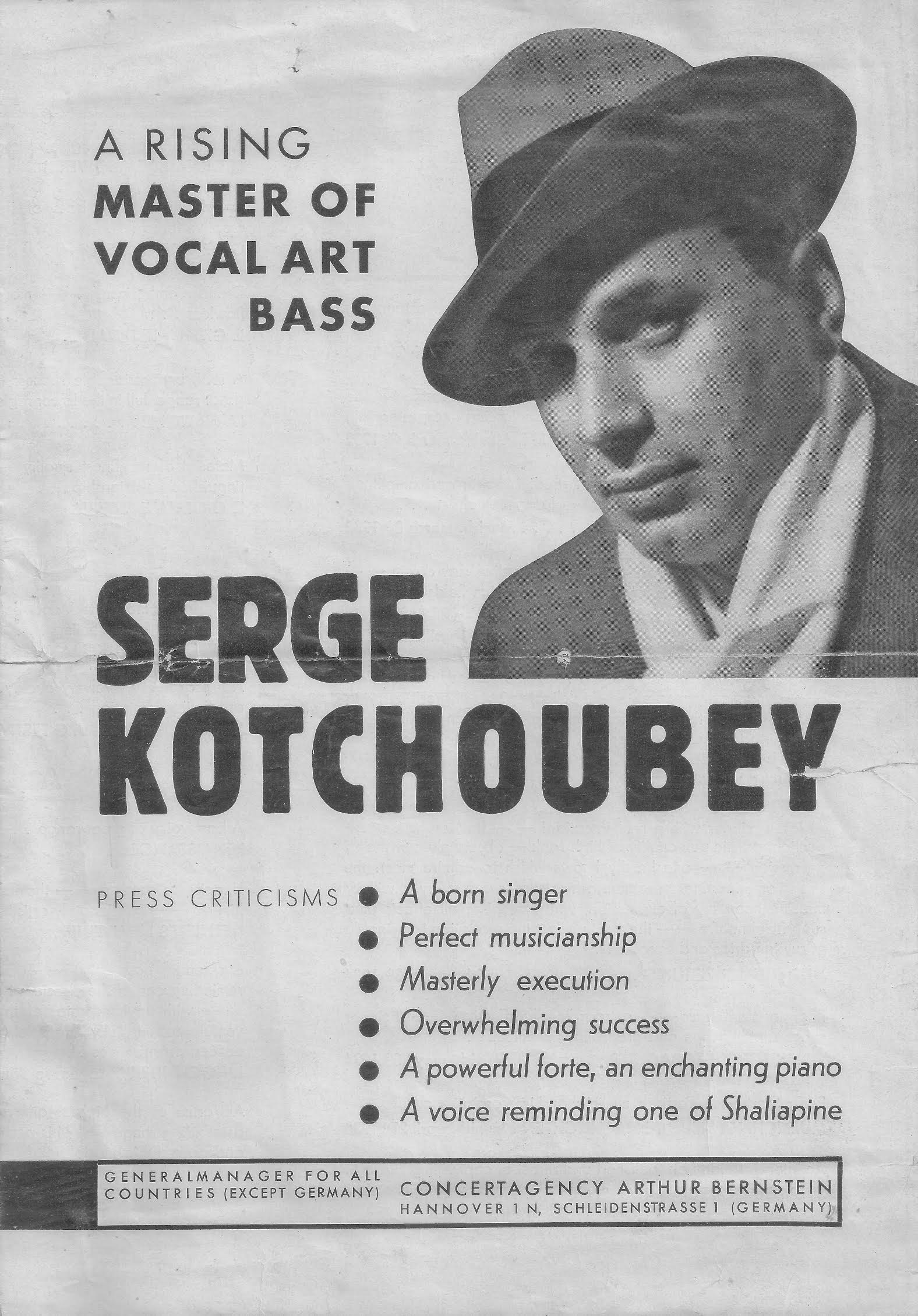

Singing: A lifelong Passion.

A few months before Sergei was born, the Kiev opera house which had been built in 1856, caught fire on February 4th, 1896 and burnt down. By 1901, a new building in the neo-Renaissance style designed by academician Victor Shreter was once again open. The official opening was on September 16th, 1901 and Wilhelm Harteveld’s cantata Kiev, which was written exclusively for re-opening was performed along with A Life for the Tsar by M. Glinka, who would become one of Sergei’s favorite composers (source: http://www.opera.com.ua/en/about/). A few years after the grand re-opening, Sergei would be taken to the opera by his grandmother, Nelly. They would stay in the family’s apartment in Kiev and attend the opera in all their finery. The arrival of Elena Sergeievna now living with her “4th” husband Alexander Yagn with her grandchildren in tow was always an event.

So in addition to his father’s theater in Voronki, the musical evenings at home, it is clear that Sergei’s grandmother was one of the first influences on his musical career. Sergei would recall years later in his grand apartment in New York, with its soaring ceilings and tall windows looking out unto 96th Street that whenever the family went to the Opera in Kiev, he had to sing the Aria’s of all the protagonists to his grandmother. While his brother Misha was a talented singer, too, it may have only been Sergei who was tasked with this assignment as he already had incredible memory, musicality, and tonality as a young boy.

Following the successes of the General Platoff Don Cossack tours, Sergei’s love of music led him to move to Florence Italy to study Bel Canto in early 1930. The move was as much a chance to study opera as it was a way to stay close to Russia in case te Bolsheviks lost power and he could return home. He studied with Signora Ernesta Bruschini. Her speciality was training soprano voices and her sister was the famous Italian soprano, Mathilde Bruschini. Whatever the situation, Sergei was immediately introduced to the musical world of Florence & Milan and more broadly Italy. His first big break was in the Opera di Pistoia where he sang in numerous operas and appeared in a number of recitals. This was a grand launchpad for a career that would span over 20 years in opera.

In addition to Bruschini, one of the central figures in both Sergei and his family’s Italian years was Adrian “Adriano” Ksenofontovitch Harkevitch / Адриан Ксенофонтович Харкевич (1877–1961) and his family. Adriano was the son of a village priest. Years before the Russian revolution, he had graduated from the Kremenetsky Seminary in St. Petersburg / Кременецкой духовной семинарии в Санкт-Петербургской (see: http://zarubezhje.narod.ru/tya/Kh_054.htm) and shortly after graduating, he moved to Italy. In time, he made his way from Rome to Florence where he settled and became the choir director of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Nativity in Florence, Italy. Adriano was passionate about music and especially liturgical music which had flourished in 19th century Russia under the patronage of the Tsars and the participation of famous Russian classical composers like Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky and liturgical composers like Nikolai Kedroff. Adriano, like many choir directors was also a composer. The Harkevitch family had a very close relationship to their beloved church in Florence after all, Adriano’s wife, Anna Vladimirovna (née Levitskaya) / Анна Владимировна Левицкая was the daughter of Protoirei Vladimir Levitsky / протоиерея Владимир Левицкий (1842–1923) who built the church in Florence.

It was a sanctuary that had been visited by Sergei’s grandmother Nelly many years before and it was as close a family parish church as Sergei could hope to have in emigration. As a young Russian Orthodox Seminary graduate living in Italy, Rome was the first obvious destination. But after a short period in Rome, Adriano moved to Florence where his first role in the newly built church was that of psalmist / псаломщик. His role quickly evolved and from the 1920s until well into the 1950s, he was the choir director of the church as well as the chief librarian. On a cultural level he was enthusiastic about organizing Russian orthodox liturgical musical concerts. During the years of Fascism and the allied liberation of Florence, many of these pursiuts had to be put aside in favor of more important works. In collaboration with the much loved and admired Orthodox priest, Bishop (Prince) Ioann Kurakin / Епископ Иоанн (в миру князь Иван Анатольевич Куракин; (1874-1950), he was a key support for the man who would be responsible for saving the lives of many Russians who took refuge in the church in the 1940s. Among the people who were protected by Adriano and Father Ioann were Count Nicholas Dmitrievitch Cheremeteff / Николай Дмитриевич Шереметев (1904 -1979) and Count Leon Alexeivitch Bobrinsky / Лев Алексеевич Бобринский (1918-2010), both of whom hid in the basement of the church in fear of being arrested by the Italian Fascists or the German Gestapo. His daughter Nina Adrianovna Harkevitch / Нина Адриановна ХАРКЕВИЧ (20.11.1907-22.071999) would become a lifelong friend of the family and years late would visit Sergei’s wife Irina in the U.S. (source: http://www.artrz.ru/menu/1804681482/1804787938.html).

Father Ioann was perhaps unusual in the traditions of Orthdox priests but in emigration, he along with many Russian aristocrats chose to serve Goad and the Russian orthodox community as priests. In Paris his distant cousin, Prince Nikolai Nikolaivitch Obolensky after completing his wartime duties as a soldier in the French army became a priest and served for many years at the Russian Cathedral of Alexander Nevsky on rue Daru. Father Ioann was a cultured and worldy gentleman who served as Deputy in the Russian State Duma before the revolution. He became a priest after the death of his wife and she bore him several children. His wartime efforts helping the Florentines bury their dead after the allied bombardments endeared him to the Italian community. He was a friend of the Kotchoubeys and often at their apartment. he had a wonderful sense of humor and enjoyed life’s little misadventures. One story of Andrei Sergeievitch (1938-) as a six year old altar boy on his first service at the church saw him walking through the holy doors with a basket of communion bread / prosfirki. While Sergei Mikhailovitch, the starosta at the church was about to scold his son, Father Ioann just laughed and calmed his friend down. In 1950, Father Ioann was made Bishop of Messina by Metropolitan Evlogi of Paris but died shortly after his enthronement.

The Orthodox community in Italy extended beyond the Russian community and it meant that the church would on occasion also welcome Queen Elena of Romania (née Princess Helen of Greece and Denmark )and her sister Irina, Duchess of Aosta (née Princess Irene of Greece and Denmark ) (1904-1974). Their presence was not unusual as they were both Orthodox by birth and a quarter Russian as their grandmother was the Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna who was married to King George I of Greece. The Queen Consort of Italy Elena (née Princess Elena Petrović-Njegoš of Montenegro ) (1873-1952) was also born Orthodox and educated at the Smolny Institute in St. Petersburg. She was introduced to a large swath of the Russian Imperail court as a young lady and continued to maintain ties with Russians throughout her reign. She did convert to Catholicism after she married her husband, the future King Vittorio Emmanuelle III (1869-1947). Sergei Mikhailovitch knew the Queen and gave recitals at the royal residences. We know he was in Rome in 1937 from a brief online article, the artist, poet and composer Valeria Florianovna Denervo-Morgunova / Валерия Флориановна (урожд. Денерво-Моргунова) (11.04.1918-) recalls a visit to Italy with the scouts in 1937 where they met the king and were subsequently invited to Florence by Sergei Mikhailovitch :

see: http://www.rv.ru/content.php3?id=7495

…В 1937 году Валерия приехала в Италию с группой скаутов. Там произошла её встреча с королевой Еленой (которая воспитывалась в Смольном, была дружна с Вырубовой, приведшей Распутина к императрице) и её мужем – королём Италии Виктором-Иммануилом. Воспоминания Валерии Флориановны полны очарования и непременного юмора, их можно слушать бесконечно:

«Это был маленького роста, очень умный король. Я его очень любила и помню те времена, когда, вынимая платок из кармана, он говорил: «Это – единственное место, куда я могу совать свой нос», имея в виду правящий режим Муссолини. Королева Елена была председательницей на чаепитиях каждое воскресенье после литургии. Однажды меня попросили сыграть, моя игра понравилась князю и княгине Кочубей, и я получила приглашение посетить Флоренцию. А там я встретилась с композитором Гречаниновым и сказала, что больше всего на свете люблю его два романса. На самом деле я тогда только их и знала из его произведений. И он пришёл и подарил мне ноты, а это оказались именно мои любимые романсы. Тогда же стали проводиться мои концерты. Но в моей жизни уже преобладало влияние рифмы и поэзии».

Translation:

…in 1937, Valeria arrived in Italy with a group of scouts. This is where she met Queen Elena (who studied at the Smolny, was friendly with Wyroubova, who introduced Rasputin to the Empress) and her husband – the King of Italy Vittorio Emmanuelle. Valeria Florianovna’s memoirs are full of quaint and original humour, which one can hear without end.

“He was small in height and was a very intelligent king. I loved him very much and I remember the time when he would take out a handkerchief from his pocket, “this is the only place where I can put my nose, ” in reference to Mussolini’s power. Queen Elena would oversee the teas that were held every Sunday after the Liturgy. One day they asked me to play and it please Prince and Princess Kotchoubey who invited me to visit Florence. There I met the composer, Gretchaninov and told him that more than anything in this world, I loved his two romances. At the time, it was the only two works that I knew from his work. He came and gave me notes as gift, which turned out to be my favourite Romances. At that point, I began giving concerts. But in my life at that point, I began to absorb the influences of rhythm and poetry.”

Aleksandr Tikhonovich Gretchaninov / Александр Тихонович Гречанинов (1864 – 1956) was born in Moscow and lived through the dawn of the tumultuous 20th century. He passed away in New Jersey, United States in 1956. He was a Russian composer who was a friend of Sergei Mikhailovitch. A number of his compositions were dedicated to Sergei and they collaborated on a number of performances of his work. Gretchaninov was already a renowned composer by the time of the Russian Revolution having studied under Nikolai Rimsky Korsakov he later pursued musical composition for opera, romances and the Russian Orthodox Church. He emigrated in 1925 to Paris, France (and then to the USA in 1939) but spent time in Florence, Italy and was a friend of Adrian Harkevitch, too. Hs friendship with Sergei Mikhailovitch extended to their mutual love of Cossack songs and they were both associated with the General Platoff Don Cossack Group. A.V. Savchuck, a renowned singer in the chorus recalled with pride how Gretchaninov reacted to his performance of a leading role in one his opera’s in the 1950s (see: http://generalplatoffdoncossackchorus.com/biographical-information/). On December 1, 1955, the Chorus sang at the University of Iowa and performed the Credo by Gretchaninov, Sergei Mikhailovitch was a featured soloist that evening but sang with the chorus, his friend’s musical composition to the creed.

Another person who came into Sergei’s life was a fellow countryman, choir director and composer Boris Mikhailovitch Ledkovsky (1894-1975) who was born in Agrafenovka, Russia (near Rostov). The friendship would be carried from Bulgaria to Germany and ultimately to New York and always in the cradle of liturgical music which was an important constant in Sergei’s life. Like the Harkevitch’s, Ledkovsky came from a family of priest in southern Russia. After studying theology, he left woth the white Russian emigres to settle in Sofia, Bulgaria where he was regent in the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. In 1937, he formed the all male ensemble, “Black Sea Cossacks Choir” in Germany and with his help, Sergei recorded a number of records in Germany under the Polydor label. Among the records that were made is (see: http://www.russian-records.com/details.php?image_id=19339#nav): Der Vergessene (M. Mussorgsky) S. Kotschubey mit orchestre; Nächtliche Heerschau (M. Glinka) S. Kotschubey, Bass mit orchester. Unfortunately, the factory was bombed by the allies and the recordings have largely all been lost having been made in 1942-43. Like Sergei, Ledkovsky, his wife Marina and their four children emigrated to New York, USA but a few years earlier in 1951. Once again, in each other’s company, Sergei sang for him in the Russian Orthodox choir of the Our Lady of the Sign Cathedral in New York from 1953 until his death in 1960 although Ledkovsky would continue conducting until his death in 1975 (see: http://www.rocm.org/e_aboutchoir.htm). With the church and music as the constant thread that unified the Russian community abroad, Ledkovsky led the choir at Sergei’s funeral and his son Alexander, led the choir at the funeral of Daria Constantinovna Kotchoubey (née Princess Serenissime Gortchacow) in 1992.

Noted Concerts:

1928, Cairo Opera House: Claudio Monteverdi, L’Orfeo (or La Favola d’Orfeo) Scenery and Costumes: Emanuele and Cito Filomarino. Producer: Vincenzo Sorelli. Singers: Spartaco Marchi, Isora Rinolfi, Mateldo Ceccherini and Sergio Cocciubei.

30. JÄNNER 1938 , SONNTAG · 16.30 UHR

| ANTON KONRATH Dirigent |

| ANTON DERMOTA Tenor |

| ROSE MERKER Sopran |

| SERGE KOTCHOUBEY Bass |

13, 16, 19, 22 ottobre 1938, Stagione Lirica Autonnale, Teatro Comunale «Vittorio Emanuele II» di Firenze. Un Ballo in Maschera. ripresa (per il 4° Maggio Musicale Fiorentino). melodramma tragico in 3 atti, 6 quadri e 17 scene di Giuseppe Verdi, libretto (versione “di Boston”) di Antonio Somma (da Eugène Scribe: “Gustave III ou Le bal masqué”), dirige Mario Rossi, maestro del coro Andrea Morosini, regia di Ugo Bassi, scenografia di Primo Conti {soprani drammatico Gabriella Gatti (Amelia) e leggero-lirico coloratura “en travesti” Jolanda Bocci (Oscar), contralto drammatico Maria Benedetti (Ulrica), tenori lirico Antonio Bagnariol (Riccardo di Warwick), Adelio Zagonara (giudice) e Gino Martini (servo), baritono Armando Borgioli (Renato), bassi di carattere Camillo Nannini (Silvano), Ugo Novelli (Samuel) e Sergio Cocciubei (Tom)}

Donnerstag 22, Oct. 1942, Berlin, Blache & Mey. Arien und Lieder. Am Flügel: Hermann Hoppe.

Jan. 9. 1946 Lyceum Club Internationale di Firenze – “Sergio Kotchoubey con la collaborazione pianistica della Signora Adriana Dolenti Romanelli”:

Sala di Santa Cecilia, venerdì 26 gennaio 1940: Concerto della soprano Maria Teresa Pediconi e del basso Sergio Cocciubei (see: http://opacapitolino.cineca.it/Record/RMR0055494)

24, 26, 29 aprile 1933, Royal Opera House

Gaetano Donizetti LUCREZIA BORGIA

don Alfonso d’Este: Tancredi Pasero

donna Lucrezia Borgia: Giannina Arangi Lombardi

Gennaro: Beniamino Gigli

Maffio Orsini: Gianna Pederzini

Jeppo Liverotto: Emilio Venturini

don Apostolo Gazzella: Sergio Cocciubei/Giacomo Merletta

Ascanio Petrucci: Amleto Galli

Oloferno Vitellozzo: Sante Messina

Gubetta: Attilio Bordonali

Rustighello: Luigi Cilla

Astolfo: Mario Mari

direttore Gino Marinuzzi

regia Guido Salvini

scene e costumi Mario Sironi

March 29th, 1956, Bath, Maine. Concert of the General Don Platoff Chorus. S. Kotchoubey Soloist for “Twelve Robbers”

Italy, a Return Home:

Sergei’s links with Italy were not haphazard. Because of his father’s frequent absences and his mother’s humble background, Sergei’s de facto or surrogate parent was his grandmother, Elena Sergeievna. This link with her and the Volkonsky family was critical in the connections that Sergei felt for Italy.

In many ways, for this branch of the Kotchoubey family, Italy was a second home. It was home beacuse by 1909, four generations of the Volkonsky family had been buried on Italian soil. It was close to the family because Italy was always the place that they turned to for spiritual and corporal salvation. As far back as 1865, Sergei’s grandfather, Nikolai Arkadievitch had sought refuge in Venice at the Kotchoubey palazzo belonging to his cousins Prince and Princess Sergei Victorovitch Kotschoubey for a cure to his tuberculosis but ultimately succumbed to the disease. Years before, he went to Pisa with his first wife Ekaterina Arkadievna Stolypina to find a way to ease the pain in her breasts but she too died in Italy in 1852. In 1905, Sergei’s uncle, Col. Sergei Dmitrievitch Molchanov (1853-1905) died at the age of 52 in Florence. The bodies of Nikolai, his first wife Ekaterina and Sergei were all brought back to Russia for burial.

The special relationship between the family and their adopted second country, Italy started on numerous fronts with the departure of Princess Zenaida Alexandrovna Volkonskaya (née Princess Belosselskaya-Belozerskaya) (1792-1862) for Rome. From a fantastically rich family and married to the lazy and uninspired but wealthy Prince Nikita Grigorievitch Volkonsky, she became hostess to numerous salons. She was one of Emperor Alexander I many lovers, and her departure for Rome was meant to put some distance between her and her sovereign. En route to Siberia in 1826 to join her husband Sergei Grigoriovitch Volkonsky, Princess Maria Nikolaievna stopped to rest at her sister-in-law, Zinaida Alexandrovna’s palace in Moscow.

“…В Москве я остановилась у Зинаиды Волконской, моей невестки… Пушкин, наш великий поэт, тоже был здесь… Во время добровольного изгнания нас, жен сосланных в Сибирь, он был полон самого искреннего восхищения: он хотел передать мне свое “Послание к узникам” для вручения им, но я уехала в ту же ночь и он передал его А.Муравьевой”

It still stands today and is located on the Tverskaya Ulitsa and houses the famous gourmet supermarket, Elyseevskiy. Shortly after Maria’s visit, because of the displeasure she incurred from Emperor Nicholas I and vicious court rumours she moved to Rome in 1929. In a way, it was her home coming as she was born and raised in Turin, where her father, Prince Alexander Belosselsky-Belozersky was the Russian ambassador to the court of the Duke of Savoia. She only “returned” to Russia in 1817.

In Rome, Princess Zinaida built the what became the villa Volkonsky (today the residence of the British Ambassador) and it became a center of Russian cultural life. When Prince Sergei Grigoriovitch and his wife Maria Nikolaivna returned to European Russia from their exile in Siberia, they left almost immediately for a European tour, stopping in Rome where they visited the graves of Maria’s sister and mother. Her sister Sophia Nikolaievna Raevskaya / Софья Николаевна Раевская (1806 – 1881), who was unmarried, severe and a chronicler of the times had been devoted to both her mother who died in 1841 and another sister Elena Nikolaievna Raevskaya / Елена Николаевна Раевская (1803 -1852) who also died in Rome from tuberculosis. Sophia was heir to a part of her father’s estate after his death in 1829 and that of her sister Elena in 1851, following her death she returned to Russia from Rome to her estate, Sunki (Cherkass Province) under Kiev and continued a very active life. Maria and Sophia had a friendship that was reinforced by Sophia’s sense of adventure which showed when she made the long arduous trip to Siberia to visit her sister there. Sadly, Maria was never able to see her mother or sister, Elena again.

Princess Zinaida Alexandrovna was buried in the Church of Saint Vincent and St. Anastasia accross the Fontna di Trevi in 1862. As if the Italian connection was meant for everyone in the Raevsky and Volkonsky family, her brother-in-law, Prince Sergei Grigorievitch Volkonsky shared his fate in Siberia with Alexander Viktotovitch Poggio / Александр Викторович Поджио (1798-1873) who was born in Nikolaev (southern Russia) to an Italian Catholic family and an avowed Decembrist who would become a life long friend of both Prince Sergei and his wife Princess Maria Nikolaievna Volkonskaya (nèe Raevskaya). Alexander Viktorovitch was buried on the Voronki estate in 1873. The friendship with the Poggios introduced another important link between the Volkonsky family and Italy.

When Elena Sergeievna married her third husband, Alexander Alexeivitch Rakhmanov in 1869 she gave birth to her oldest daughter Maria Alexandrovna in 1871 in Kiev but she gave birth to her youngest child, Elena Alexandrovna when she was already 40 years old in Florence in 1875. Her nephew, Prince Sergei Mikhailovitch Volkonsky would write in his reminiscenses published in 1925, that Elena Sergeievna was a frequent visitor to Italy and most specifically to Florence, Naples and of course Rome. It was not a surprise that her eldest daughter, maria Alexandrovna would marry a Russian of Italian descent, Alexander Ivanovich Giuliani / Александр Иванович Джулиани (1870-1941).

Colonel Alexander Ivanovich had an Italian name but he was already enobled by the Tsar, an Orthodox Christian and a Russian subject. He hailed from St. Petersburg. Like many noblemen, he was educated in the Nikolaevsky Kadestsky Korpus / Николаевский кадетский корпус and graduated in 1892 when he began his officer training at theNikolaevskiy Engineering School / Николаевское инженерное училище after which he was commissioned in the 9th Battalion of Sapers / 9-й саперный батальон. He was transferred to the Life Guards regiment in 1895 as a sub-Lieutenant / Подпоручика гв. (ст. 12.08.1895) where he rose through the ranks first as a Lieutenant / Поручик (ст. 12.08.1899), Staff Captain / Штабс-Капитан (ст. 12.08.1903), Captain / Капитан (ст. 12.08.1907) and then Colonel / Полковник (доп. к пр. 22.03.1915) at the start of WWI. Like his Kotchoubey nephews, he joined the Volunteer army in the summer of 1918 /Добровольческой армии (с лета 1918) and served in the department of External Affairs and technical troops / отдел внешних сношений штаба ВСЮР и технич. войсках. His sons Sergei Alexandrovitch Giuliani / Сергей Александрович Джулиани (1896-?) and Mikhail Alexandrovitch / Михаил Александрович Джулиани (1897-?) both served with their father and cousins in the Volunteer Army / Добровольческой армии).(see: Соч.: воспоминания в сб. «Памятные дни». Ревель, 1930-е в 3-х тт)

He was already married to Maria Alexandrovna Rakhmanova in the 1890s and their sons Sergei and Mikhail evacuated with them from Novorossisk, Russia. They stopped temporarily in Greece on the island of Antigone before leaving for Sofia Bulgaria in 1921. There they were reunited with their nephews Sergei and his brothers (with the exception of Vassili who had perished at sea on a barge during the November 1920 evacuations). While the surviving Kotchoubey brothers decided to stay in Bulgaria, Alexander Ivanovich and his wife Maria Alexandrovna left together with their sons shortly after arriving in Sofia for Florence, Italy. There they arrived in the spring of 1921 and stayed until their death. Alexander Ivanovitch took Italian citizenship. After the Revolution, life was difficult and they had to survive on the little that they had. Alexander Ivanovich was a devoted soldier until the end and he was elected president of the Society of the 1st Life Guards Regiment for many years / Председатель Объединения л.-гв. 1-го стр. полка (на 12.1924; на 27.11.1927; 1935-39). (Source: http://ria1914.info/index.php/Джулиани_Александр_Иванович).

He and his wife are buried in the Allori Cemetery in Florence:

Giuliani, Alessadro di Giovanni, age 70

born in St. Petersburg on ?

died in Florence 31/III/1941 at 5:50 am

Nationality: Italian

entombed 2/IV/1941 at 11:30 am

Tomb; V I 08s

His wife who survived him by more than 10 years is buried with him:

Rakhmanoff, Maria di Alessandro, age 81

born Kiev on 31/VII/1871

died Florence on 3/XII/1952

Nationality: Russian

entombed 5/XII/1952

Married to Giuliani

Tomb: V I 08s

When the photograph above was taken, in February 15, 1917, he was a decorated soldier. He was decorated with the order of St. Stanislas 3rd degree / Св. Станислава 3-й ст. (1902), the order of St. Anna 3rd degree / Св. Анны 3-й ст. (1908) and St. Stanislas 2nd degree /Св. Станислава 2-й ст. (ВП 23.04.1915) for outstanding service. He fought in a number of Russian Imperial conflicts and is picture near the end of WWI as a Major General in His Majesty’s Life Guards Infantry regiment / 1-й стрелковый Его Величества лейб-гвардии полк which would be reorganized the following year after the fall of the Imperial government and the start of the Civil War.

Maria Alexandrovna and Alexander Ivanovitch’s son, Mikhail “Misha” Alexandrovitch stayed with his wife in Italy for a few years. Their son, Alexander Mikhailovitch / Александр Михайлович ДЖУЛИАНИ (12 июля 1921, Италия – 17 (18) июня 1989, Франция) was born there on July 12, 1921. The family subsequently moved to Nice, France in 1926 to the Villa Baron and then in 1936, they moved to France. Their descendents continue to live there. Sergei Alexandrovitch, their oldest son stayed with his parents in Florence and died there in the late 1950s.

The years following their arrival was indeed difficult and the family sold what few possessions they had to make ends meet. In 1925, Sergei Alexandrovitch, who inherited the portrait from his parents was forced to sell the 1826 Sokoloff watercolour of his great grandmother Princess Maria Nikolaivna Volkonskaya with her infant son Prince Nikolai Sergeieivitch Volkonsky. At the time, it may not have been worth very much and certainly not worth the hassle of contacting his Volkonsky cousins in Rome or his Kotchoubey cousins in Bulgaria to see if someone from the family wanted to purchase it. perhaps he was too ashamed to be selling the portrait and wanted to keep it from his broader family. What ever the reasons, the portrait itself was painted the week of Maria Nikolaevna’s departure for Siberia to join her husband. On the strict instructions of the new Emperor Nicholas I, the infant (and all the children of the Decembrists) remained in St. Petersburg with his grandmother but died shortly after his mother’s departure. the watercolour had traveled from St. Petersburg to Siberia where it hung in Irkutsk for twenty years. Then with the return of teh Volkonskys to European Russia it found its way to Voronki until in 1886 it hung in the main house at Veisbakhovka. The watercolour was given my Elena Sergeivna to her eldest daughter Maria Alexandrovna and it stayed with the Giuliani’s through the Civil War, Bulgaria and finally Italy where it hung in their apartment in Florence until it came into the possesion of young Sergei Alexandrovitch.

The watercolour was being carried by Sergei Alexandrovitch to an antique dealer in Florence and on the way he bumped into his mother’s third cousin by marriage, Vladimir Nikolaevitch Zvegintsev / Владимир Николаевич Звегинцов (11.02.1891-27.04.1973), who was only a few years older than Sergei. His “uncle” Vladimir Nikolaivitch was the husband of Anastasia Mikhailovna Zvegintsiva (née Raevskaya) Анастасия Михайловна Раевская (1890-03.02.1963), a lady-in-waiting to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and a third cousin to Maria Alexandrovna. They had been married on 28.04.1913 in St. Petersburg. When he learned that the watercolour was being sold he immediately offered to buy it. Vladimir Nikolaivitch was born on his family estate of Petrovskoe-Zvegintsovo Novokhoperskovo in the Province of Voronezh. He was not only a Colonel in the Chevaliers-Gardes having finished the Corps des Pages but like Alexander Ivanovitch he had also fought in WWI but was wounded. His passion as his son after him was the Russian military. In addition he was passionate about the lives of the Decembrists who had served in the Chevaliers-Gardes. Prince Sergei Grigorievitch Volkonsky had served in the Guards and was of course married to the subkect of the Sokoloff watercolour. From 1956, he was the editor of a newsletter on the Guards called, Вестника Кавалергардской семьи and then along with Vassili Vassilievitch Kotschoubey (1892-1971), another was a contributing editor to «Военная быль». He was an author to a number of books which included, “Кавалергарды в Великую войну и Гражданскую (Т. 1–3. Париж, 1936–1966). ”

As a student of the Decembrists and their incredible journey, no one would have appreciated the watercolour as much as Vladimir Nikolaivitch. He new in his heart that the portrait did not belong in a private home even if it was of immense sentimental value. The recent death of his first wife in 1963 meant that the Zvegintsev’s link with the Raevskys had finally been closed and it was time to return the painting back to its country of origin. The portrait’s return to Russia began with a visit to Paris by the academic and art historian Ilya Samoilovitch Zilbershtein / Илья Самойлович Зильберштейн who came to visit Denis Dmitriovitch Davydoff (the descendent of the Decembrist, Vassili Lvovitch Davydoff / Васили Львович Давыдов who was convinced to send the family album to Russia instead of remaining in family hands. Denis Dmitrievitch immediately introduced another of his friends in a similar conundrum, Vladimir Nikolaivitch.

It was completely by chance that the two met. In Vladimir Nikolaivitch’s archives was a 60 volume tome of literary works dedicated to the Decembrists. In one of the books was a copy of Sokoloff’s Volkonsky portrait with an indication that its whereabouts were unknown. Ilya Samoilovitch was devastated to learn that the portrait was lost to history and could not believe his ears when Vladimir Nikolaivitch, said, “well, I have that watercolour.” It did not take much time for the Soviet Art historian to convince Vladimir Nikolaivitch who agreed that Piotr Feodorovitch Sokoloff’s tender watercolour should be in Russia. It arrived on 30.11.166 in the USSR and was immediately gifted to recently created State A.S. Pushkin Museum in Moscow / Государственном музее им. Пушкина в Москве (www.pushkinmuseum.ru). Davydoff’s photoalbum was gifted as well. The arrival of the watercolour to the Pushkin Museum in Russia was a fitting journey for a woman who not only inspired six of Alexander Sergeivitch Pushkin’s seminal works and poems but is seen as one of the heroines of 19th century Russia for her selfless sacrifices in the name of honor and duty to her husband and their family. Vladimir Nikolaivitch recognized this and he wrote to Ilya Samoilovitch:

“…Конечно, вы правы, говоря, что место окончательного “упокоения” акварели на родине и что пора ей закончить свое долгое путешествие. К этому же заключению пришел и я… Уже раз ей грозило закончить свое существование у какого-то флорентийского антиквара. В лучшем случае была бы она куплена любителем красивой акварели, но уже, наверное, никто бы со временем не знал, кого она изображает, и для потомства и для русских музеев она навсегда была бы потеряна. Уже несколько раз у меня были предложения ее продать, но, каковы бы ни были “минуты жизни трудные”, я никогда на это не согласился и не соглашусь…

source: http://www.vestnik.com/forum/win/forum28/dashkov.htm

The return of the Volkonsky portrait to Russia was only the begining as many years later in September 2001, Elena Vadimovna Cicognani (née Princess Volkonskaya), the great granddaughter of Prince Mikhail Sergeievitch Volkonska (1832-1909) accompanied by her third cousin Andrei Sergeievitch (-1938), the great grandson of Elena Sergeievna Molchanova-Kotchoubey-Rakhmanova (née Princess Volkonskaya), gifted a number of Volkonsky archives including, watercolours, photographs and an album made when the Volkonsky’s were in Irkutsk to the Russian State Historical Museum in Moscow, Russia.

A Second Marriage and a Family:

The friendship with the Harkevitch family and the intellectual and musical union that they enjoyed was further reinforced by the fact that at an evening organized by the Harkevitch family in 1931, Sergei met his second wife, Irina Georgievna (née Gabrichevsky) / Ирина Георгиевна Габричевская (Кочубей) (13.11. 1900 -27.06.1996). He married her in Venice on the 7th August, 1932 after a whirlwind romance (his grandfather had lived and died there in 1865). Venice’s Orthodox church, Chiesa di San Giorgio dei Greci Ortodossi was the only church that was willing to overlook the absence of documents related to Sergei’s defunct marriage to Evgenia Victorovna whom he left behind in Sophia Bulgaria. A tricky family situation as his brother Misha was still happily married to her sister Olga Victorovna. At the wedding was Irina’s older brother Georgi Georgievitch Gabrichevsky and a relative and family friend from Kiev, Ivan Mikhailovitch Lopukhin / Іван Миколайович Лопухин (1862-1942) who ended up living in Italy after leaving Russia and moving to France initially. His aunt, Anna Petrovna Issakowa (née Princess Lopukhina) /Анна Петровна Лопухина (Исакова) (?-1913) was married to Nikolai Vassilievitch Issakow / Николай Васильевич Исаков (1821 -1891), the illegitimate son of Emperor Alexander I and in turn they were the grandparents of Sergei Sergeievitch Issakow who married Ekaterina Vassilievna Kotchoubey’s daugher, Irina Nikolaivna (née Countess Mussin-Pushkin) (1921-2010).

The couple settled in the Campo de Marti neighborhood. Together Sergei and Irina had two children, Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna (1935-) and Andrei Sergeievitch (1938-). He was an active member of the Orthodox Church choir in Florence and continued to sing in a number of operas including Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Verdi’s A Masked Ball. He would perform under the batons of maestros like Furtwangler and von Karajan as well as the composer Dalla Piccola.

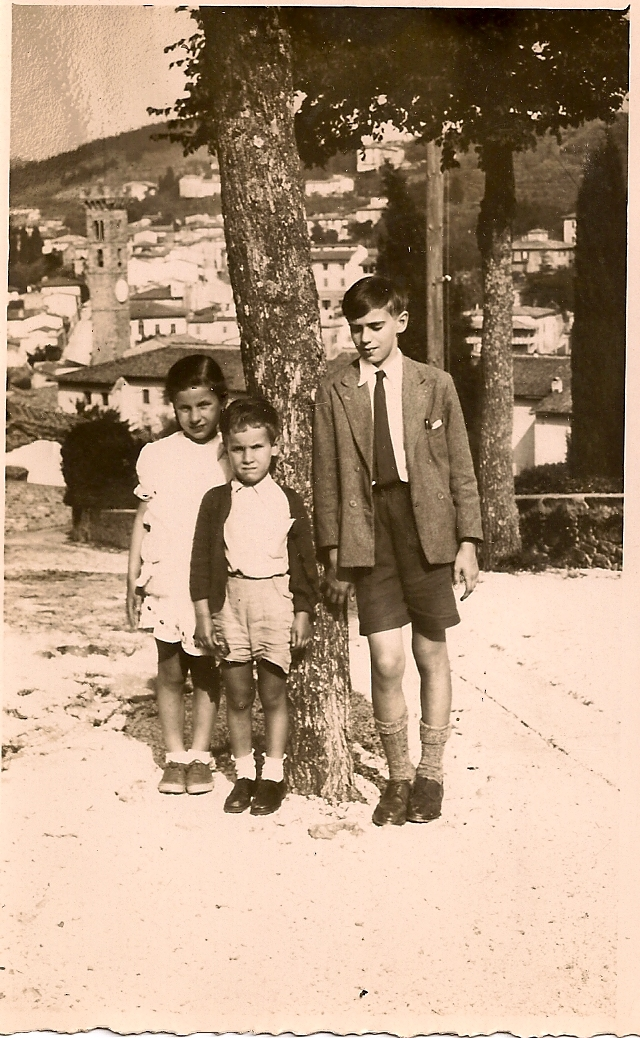

During World War II, life in Florence was active but like many cities in Europe it was no immune to the terrible tragedy of war. Families and friends would continue to gather and the Russian Imperial world which was fading fast into history was still a common thread that bound the Russian aristocrats together. In 1941, H.S.H. Prince Nikita Alexandrovitch of Russia (1900-1974), a grandson of Emperor Alexander III and his wife H.S.H. Maria Romanova (née countess Vorontzova-Dashkova) arrived in Rome in 1941 from France as the start of WWII had prevented them from returning back to Great Britain. They arrived with their two young sons Prince Nikita (1923-2007) and Prince Alexander (1929-2002) and while they were far from family and friends in London and Paris, they were quickly embraced by relatives and friends in Italy. They traveled to Florence to see Sergei Mikhailovitch and Irina Georgievna. The enclosed photo shows Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna, Andrei Sergeivitch and Prince Alexander Nikititch in Fiesole, the hills above Florence in 1943.

A few months later, Florence like many cities in Europe was also subject to Allied bombardments. The family was home when at 11:25am on September 25th, 1943, the first bombs dropped aiming at destroying the railway junction of Campo di Marte. The affected areas extended as far as the Piazza della Liberta with over 350 casualties of which 215 were fatal. The trauma of reliving the horrors of war which Sergei Mikhailovitch endured twenty years before was brought to a new generation who would see homes destroyed and neighbors perish. Luckily, family members were spared the trauma and everyone survived WWII.

Interestingly, the war years in Florence began the family’s transition towards a new life in America. While Sergei Mikhailovitch continued his singing career and traveling to Berlin to give concerts in 1942-43, his wife Irina Georgievna worked for the American Red Cross effort. In addition, the family came into contact with a distant relation by marriage, Sophia “Sonia” Tomara (one of Vassili Leontievitch’s daughters married a Tomara in the 18th century) who was married to a US Judge, William Clark. As we will see below they would become lifelong friends of the Kotchoubeys in the U.S. With the arrival of American troops to Florence, the family befriended a number of Americans including Captain Ben Burns from Indianapolis who was a frequent houseguest and looked to his “Russian” friends as surrogate parents, even if Sergei Mikhailovitch did not speak English, there was enough communication for him to be able to give Ben voice lessons. The friendship involved little adventures like adopting the family’s dog Gypsy who was brought home from a kennel of dogs left behind by US Servicemen. Andrey Sergeievitch still remembers all the war memorabilia that he received from Captain Burns but was unable to take with him years later when he moved to the U.S.

When the Kotchoubeys first arrived to new York, Irina Georgievna stayed at the home of her American friend from Florence, Molly Bernadini who lived at 45 East 82nd Street. Then thanks to Sergei Mikhailovitch’s student, Alexander “Shura” Langadas the family found an apartment at 593 Riverside Drive which belonged to Raissa Solomonovna Sapio (Shapiro). Thanks to that connection, Andrei Sergeievitch was accepted on a full scholarship at West Nottingham Academy in Maryland shortly after the family arrived in March 1953. Another friend from Florence was Jean Arnold who helped the family settle in their new home. Helen McMaster, a literature Professor at Sarah Lawrence College met Irina Georgievna in Florence through “Information Please” an information center used by many Americans for help in getting valuable advice while in Florence. When Nelly applied for college to Sarah Lawrence she had a letter of Recommendation from her. It was as if the war years and the post war period in Florence had been designed to ease the move to New York.

After the war, Sergei found work singing in Lugano Switzerland for Radio Monteceneri (Radio Svizzera Italiana). In 1953, a whole generation of family had now passed away. Sergei’s aunt, Elena Alexandrovna whom the children called babushka had passed away after the war in 1946. Her sister, Maria Giuliani died in 1952. In addition, the challenging economic situation after the war and the fear that the hated Communists would take control in Italy, Sergei and his wife, Irina, decided to move to America (a decision that was counter balanced by an idea to move to Australia). With their savings, they bought tickets aboard the SS Andrea Doria. From their friends Judge William Clark, (the chief justice of the Allied High Commission Court of Appeals in Nuremberg, Germany) and his wife, Sonia Tomara they received the necessary support and letters of introduction to pass through passport control and onto a new life in the United States. Sonia Clark was also a descendent of Judge General Vassily Leontievitch Kotchoubey (1640-1708) and thus a distant cousin of Sergei Mikhailovitch. What the family did not pack to take with them to New York, they left for Sergei’s cousin, Sergei Alexandrovitch Giuliani and Doska Sokoloff to dispose of appropriately. Sergei received the keys to the apartment and agreed to sell whatever was left. For Sergei Alexandrovitch it was much needed money. So began another chapter for Sergei in a new world. At this point, it was clear that there was no chance of ever returning to Russia.

In 1953, Sergei and his family settled in New York, NY USA. Imagine his joy of being reunited again with his beloved Gen. Platoff Don Cossack chorus soon after the family’s arrival in NYC. Sergei toured again in October and November 1955. His family still has the letters that he sent from Ohio, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Nebraska, Utah, Oregon, Washington, California, British Columbia and Saskatchewan where the chorus performed. Since the last time he toured with the Chorus in Europe in 1931, Sergei had now become an accomplished and renowned opera singer and perhaps this explained his disappointment with the quality of the chorus. He would not return on tour with them but it was a moment to relive an earlier more innocent time in his life and reflect on the circular nature of events.

As he did in Florence, Sergei sang in the Russian Orthodox Church choir, this time at the Synodal Cathedral of the Icon of Our Lady of the Sign of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia on 93rd Street, NY, NY. While he spoke almost no English, he continued to teach singing, horseback riding and performed numerous concerts in New York, including Carnegie Hall.

He died at home from complications of a stroke on December 25th, 1960 surrounded by his family.

*pre-1917, the dates are under the Julian calendar