(b. Voronki, Tchernigov Province, Russia 20 January 1891 – d. 3 December 1972, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada)*

Born on the Steppe: Voronki

Elena Mikhailovna / Елена Михайловна Кочубей (Викберг) (1891-1972) was the daughter of philanthropist, playwright, and photographer Mikhail Nikolaievitch / Михаил Николаевич Кочубей (1863-1935) and a local beauty, Pelegea Dmitrievna Onoshko / Пелагея Дмитрьевна Онощко(1863-d. December 19, 1930). In addition to her legendary beauty, she would become recognized for being the driving force behind the success of Voronki as a commercial enterprise and remained in the village until her death in 1930. Sergei’s father abandoned the family and Russia in years after the civil unrest in Ukraine, in 1905-1907. He departed for France in 1913 where he died on the Cote d’Azur in 1935.

She was born on his Grandparents’ estate (Nikolai Arkadievitch and Elena Sergeievna (née Princess Volkonskaya) that was called Voronki (Вороньки (Черниговская область). The estate is located in the southern part of the Tchernigov province which is north of Kiev (today Bobrovitskiy Region) on the banks of the Supoi river. Even today, it is renowned for its unspoilt beauty and incredible nature. As of 1782, the property belonged to the Miloradovich family who had married into the Kotchoubey family in the early 18th century. It was purchased by Arkadi Vassilovitch for his son Nikolai in 1850. The land is characterized by vast plains punctuated by stands of pine trees which are separated by meandering rivers and beautiful lakes. Its historical significance today is largely due to the facts that the Kotchoubey’s lived there and the fact that the Decembrist, Prince Sergei Grigorovich Volkonsky and his wife, Princess Maria Nikolaivna (née Raevskaya) both died and were buried on the estate. There is a contemporary commemorative monument to them and their fellow exiled Decembrist, Alexander Poggio but the original chapel designed by Alexander Yagn and gravestones were destroyed in the 20th century.

Today this region is in Ukraine, and for 400 years it was part of a geographic region that was historically tied to the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The first Kotchoubeys to arrive in the region in the early 17th c. settled in and around Baturyn, which at the time was the capital of Tchernigov. The family played an important part in the history of this illustrious Cossack host, Imperial Russia and establishing Ukraine’s brief independence under the last Hetman before the rise of the Soviet Union.

Nelly was the only daughter and second oldest. She had one older brother and three younger brothers, Vassili, Nikolai, Mikhail & Sergei. Elena was educated at home until she was sent, like other young girls to boarding school. Unlike her brothers who were sent to St. Petersburg, Nelly was sent to Ekaterininsky Institute (Catherine) in Moscow in 1898 and she is pictured with a class mate in the school uniform in the photo above.

Marriage and Children:

After graduating, Nelly came home to Voronki to join her mother, and her grandmother who by now was well established on her own estate of Veisbakhovka which had become a playground for architectural extravagance in the form of a large Neo-Old Ukrainian and Victorian mansion which was designed by her common law 4th husband, the renowned architect, Alexander Yagn. The year was 1907-1908 and her mother had arranged for a tutor to come and educate the youngest children including Kolya (born 1894) and Sergei (born 1896). They hired a handsome nordic gentleman with piercing blue eyes in the form of a Russian of Finnish descent from Kharkov called Dmitri “Mitya” Axelievich Wickburg / Дмитрий Акселевич Викберг (1892-April 1924). He arrived at Voronki on one of his first teaching assignments. one of his two older brothers was Boris Axelievitch Wickberg / Борис Акселевич Викберг (1886-1938) who at the time was advancing well in his studies and destined to follow an illustrious academic career. Years later he became a renowned professor and died while still a Profosser of the Mathematics and Mechanics department of the University of Perm and the Dean of its Physics-Mathematics department (see:www.psu.ru/files/docs/ob-universitete/smi/knigi-ob…/prof_psu.pdf) . The brothers were born in the village of Parkhomovka (Bogodukhovsky region) in the province of Kharkov.

Their father was Axel Wilhelm Ulrich Wickberg / Аксел Викберг and he was a manager of the sugar factory in Kharkov which belonged to Pavel Ivanovich Kharitonenko (1853-1914) who was among the richest Russian industrialists with a large concession on Russia’s sugar production. Axel and his wife had nine children and they included another brother Emanuel Axelievitch Wickburg / Эммануил Акселевич Викберг as well as six girls among whom were Nina Axelievna Wickberg / Нина Акселевна Викберг, Sophia “Sonia” Axelievna Wickburg / София Акселевна Викберг, Nadezhda “Nadia” Axelievna Wickburg / Надежда Акселевна Викберг and Zinaida “Zina” Axelievna Wickburg / Зинаида Акселевна Викберг. The family were from Finland but part of the Swedish minority that ruled Finland before it became part of the Russian empire. Finnish Swedes spoke Swedish at home and were close to Sweden via their historical roots but for all intents and purposes considered themselves also Finns.

Dmitri’s sister Nina Axelievna fell in love and married a distant relative Sergei Nikolaivitch Wickberg / Сергей Николаевич ВИКБЕРГ whose brother Karl Nikolaivitch Wickberg / Карл Николаевич ВИКБЕРГ was a gold and silver jewellery master in St. Petersburg (see;: http://skurlov.blogspot.de/2013/05/1849-1917.html) and together found themselves living in Zgurovka after the revolution. Zgurovka was the storied estate that had been passed down from Arkadi Vassilievitch / Аркадий Васильевич Кочубей (1890-1878) to his grandson Vassili Petrovich /Василий Петрович Кочубей (?-1940). One of the their two daughters Olga Sergeievna Wickberg / Ольга Сергеевна Викберг (15 Nov 1926, -19 Nov 2013) was born there in 1926.

The Wickberg-Kotchoubey connection was somehow expanded when many years later in 1945 Olga married another Kotchoubey relative, Duke Sergei Nikolaivitch von Leuchtenberg de Beauharnais / Герцог Сергей Николаевич Лейхтенбергский де Богарнэ (1903—1966). She was his third wife and they lived in Monterrey California. Their connection to the Kotchoubey’s: is as follows: Sergei’s paternal great-uncle Duke Evgeni Maximilianovitch von Leuchtenberg / Евгений Максимилианович Лейхтенбергский-Романовский (1847 -1901), had two daughters; one of them was Daria “Dolly” Evgenievna de Beauharnais /Дарья Евгеньевна де Богарнэ (1870-1937). Her first of three husbands was Prince Lev Mikhailovitch Kotchoubey/ Лев Михайлович Кочубей (1862-1927) whom she married in 1893 in Baden-Baden Germany. They had an unhappy and short marriage which nonetheless produced a son and two daughters who received the name Kotschoubey de Beauhranais / Кочубей де Богарнэ after their brother Prince Evgeni Lvovitch Kotschoubey de Beauharnais /Евгений Львович Кочубей де Богарнэ (1894 -1951) was given the amalgamation of a German French and Russian title and name by Emperor Nicholas II. His sister Natalia Lvovna / Наталья Львовна Кочубей (1899-1979) would become Sister Sophia, a Benedictine nun in Germany.

Another funny connection was that Duke Sergei Nikolaivitch’s father, Duke Nikolai Mayimilanovitch von Leuchtenberg de Beauhranais / Николай Николаевич Лейхтенбергский (1868 -1928) was very involved with the Cossacks of the Don, even representing their leader, Ataman Krasnov on missions to Germany during the German occupation of Ukraine in 1918. His relative, Vassili Vassilievitch Kotchoubey (1892-1971) was on similar missions to Berlin on behalf of the Hetman Pavlo Skoropdasky / Павел Петрович Скоропадский (1873 -1945). Skorodapsky’s wife was Alexandra Petrovna Durnova /Александра Петровна Дурново (Скоропадская) (1878 -1952), the daughter of Maria Vassilievna Durnovo (née Kotchoubey) / Мария Васильевна Дурново (Кочубей) (1846-?).

After the end of the Russian civil war in 1920, he helped establish the Choir of the Don Cossacks in the name of General Platov which was a competing choir to the one that Sergei Mikhailovitch Kotchoubey (1896-1960) joined in 1928 under the direction of Nicholas Kostriukoff.

Nelly fell in love with her brother’s tutor and while their courtship lasted many years, they finally married in 1909. There was a great wedding at Voronki which was held in the newly built stone church on the estate. Surrounded by the bones of the departed in their eternal resting place in the crypt and the solemnly joyful unconventional family in the main church hall, the Kotchoubey’a family were united in a great celebration of love and great hope for the future. The church service was followed by music and dancing and Mikhailo’s Kotchoubey’vski theatre was the entertainment provider for the venue. Singers from the opera company sang songs and the actors and villagers joined to provide dancing and spectacle for all the guests. Dmitri was quickly welcomed into the family by the brothers, and broader family. It was not much of a welcome as the financial state of the family was in tatters following years of reckless charitable giving, spending and mismanagement by Nelly’s father Mikhailo. By now, he had left Voronki with his new lover Natalia Dmitrieva Tregubova, the local school teacher and they were bound for St. Petersburg. The theatre, bright lights, cars and the night life of the capital were no match for the cruel Ukrainian countryside that had returned Mikhailo’s years of generosity to the local population by revolting against him and the family, especially on his estate in Kinoshivka. The bank which had stood by the family for so many years threatened to place the remaining estate of Voronki into foreclosure as Mikhailo had left heavy debts which were surely exacerbated by the revolution of 1905-1907. Nelly’s mother, Pelagea, her eldest brother Vassili and now Dmitri all pooled their resources to rescue the estate from being seized and arranged to take a new mortgage on the property. Nelly and Dmitri were now solidly in the family enterprise as full fledged shareholders in Voronki. Dmitri’s brother Boris remained in the USSR but the years ahead were not easy for the young family. They celebrated the arrival of a son, Sergei Dmitrievich Wickberg / Сергей Дмитриевич Викберг (1917-1918) in 1917. Not only was this joy arriving in the darkest days of the Revolution and months before the family would be forced to flee their beloved Voronki but 1918 was the apex of one of the world’s worst flu epidemics and it did not discriminate. In the early months of January 1918, Nelly and Dmitri would suffer the indignity of loosing their home which they had fought to save for ten years and more tragically their only child.

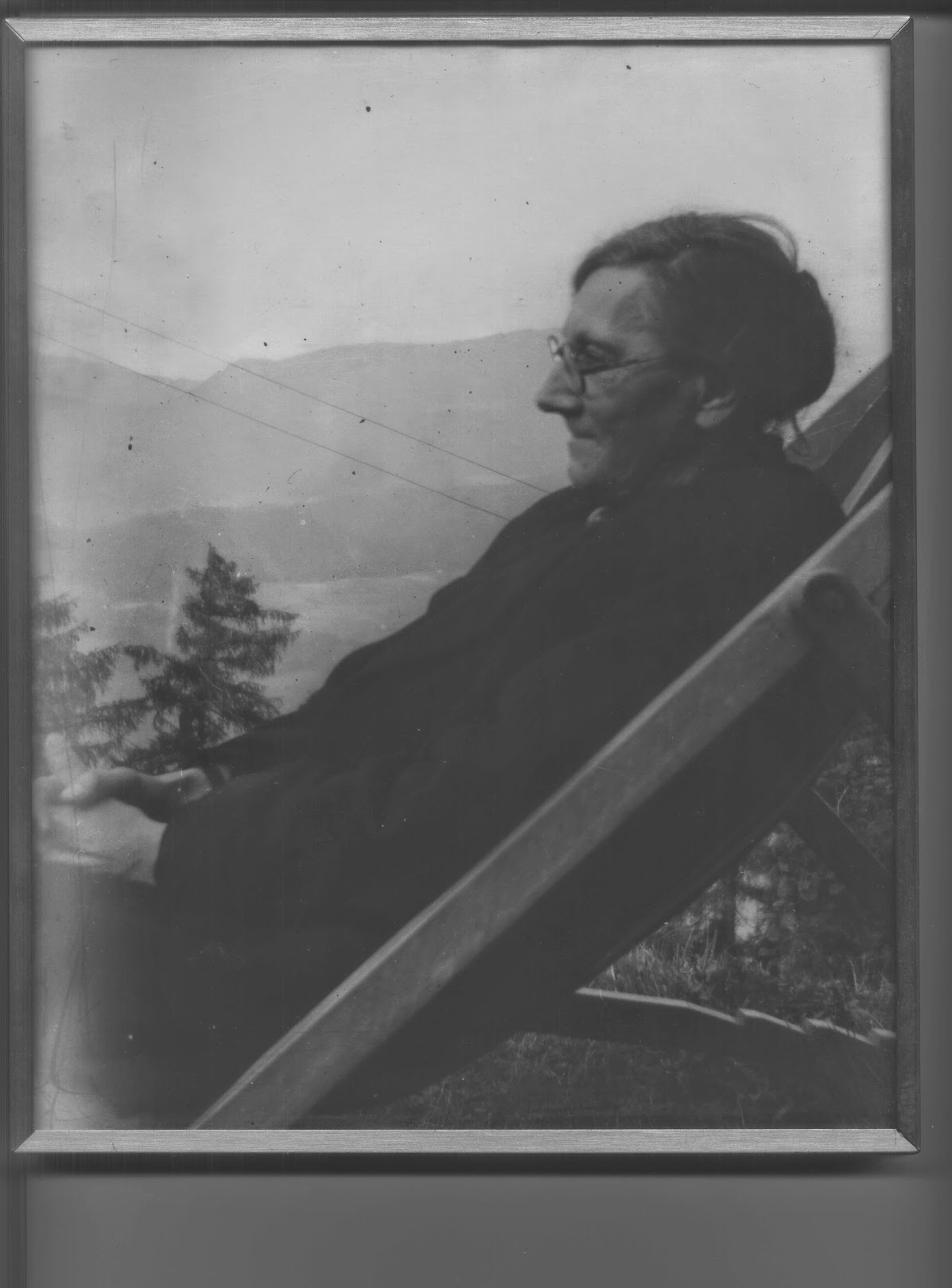

Nelly (Elena Mikhailovna) 1912 ?

Life in the Soviet Union and Emigration

Leaving Voronoki was not an act of closure as expectations were that the unrest would be quickly put to an end with the coming end of the War. More importantly, the government was now in the hands of the family’s cousin, Hetman Paulo Skoropdskiy with his aide-de-camp, non other than Vassili Vassilievitch and the commanding general of his army, another cousin by marriage Prince Alexander Dolgorouky. While Ukraine was now being occupied by the Germans in a temporary peace with the German sponsored government of Skoropadskiy, there was every reason to believe that order would return to the countryside. The family moved to their apartment in Kiev and Nelly was joined by her sister-in-law, Ludmila “Milochka” Alexandrovna Podust and her two children Olga (born 1911) and Georgi (born 1915).

1918 was a tumultuous year. With part of the family in Kiev, Nelly’s brothers all joined the Voluntary Army under Gen. Anton Denikin and were all sent to Rostov where they would put their different talents to work in the OSVAG. By the end of that year, Skoropadskiy’s government fell and a new Bolshevik movement had seized power in Kiev. Hopes of returning to Voronki were fading fast. By 1919, the focus was on the movements of the White Army and as Deniken’s army advanced north, news came that Voronki had fallen back under control of the Whites. Sergei was there and peasants were coming up to him with tears in their eyes, saying that they were forced to loot the house and returning the items back to their former owners. In the mean time, Nelly and Dmitri were pregnant again and a child was expected to be born at the end of the year. In the terrible months of the Civil War, more good news arrived when Nelly learned that her brothers Misha and Sergei had fallen in love with two sisters and married them. Misha married Olga Victorovna (née Mankovskaya) and Sergei married Evgenia Victorovna (née Mankovskaya). Some how in all that mess, people were falling in love and getting married and both brothers were taken by the spirit of camaraderie and love and following their fellow comrades into battle and love. In December 1919, Nelly gave birth to little Olya, Olga Dmitrevna Sidorowich (née Wickberg) / Ольга Дмитриевна Сидорович (Викберг) (19 December 1919 to 19 January 2007 Hamilton, Ontario Canada).

Nobody knew it at the time but 1920 would become the year that would forever break the close knit Kotchoubey family apart. Nelly remained in the new Soviet Union with her family. When her brothers and their wives decided to leave the Crimea with the evacauation of the White Army from Russia in 1920, they sent word to Kiev for the family to join them. By the then Nelly and her young two-year old daughter Olga was beside herself with worry especially as her child had a cold and she was afraid of the train ride to Odessa. She had lost her beloved son to the flu and it was out of the question that she would risk loosing another child. Dmitri was in contact with his own family and they had no plans to abandon Russia. Vassili Mikhailovitch’s wife Ludmila Alexandrovna (née Podust) also stayed behind with her children who were slightly older but they too were worried about the journey’s impact on their health. The concerns for colds and health seem minor in comparison with the real dangers of train travel during the end of the Russian Civil War when Reds and Whites took turns blowing up railway lines and railroads. Thus, it seemed that the grandmothers, the mothers with small children chose to stay behind. Perhaps it was not only a question of joining her brothers in Crimea, or traveling in the bitter November cold with a young child, perhaps it was the knowledge that it was too heart wrenching to abandon her mother Pelageya Dimitrievna.

Years passed and life in Kiev had a momentary deprive due to the introduction of the New Economic Policy (N.E.P.). The family found odd jobs for money and were somehow able to stay out of the crosshairs of marauding commissars looking to persecute landed nobility and gentry. In 1924, tragedy struck again when Nelly’s husband Dmitri passed away.

Years after Dmitri died, Nelly found love again and married in a simple civil wedding in Kiev. Once again she would have a man to take care of her.

With the arrival of the occupying German army into Kiev in 1941, Nelly began to harbour a secret hope that the Germans could bring back the world that she knew before the revolution. After all, she never believed in Bolshevism despite her daughter growing up a committed communist in the oppressive state that became the Soviet Union. Nelly decided to cast her lot with the Germans and she made quick work of her language skills to establish contacts. The war thundered on and soon it was clear that the Red Army, with her nephews Georgi Vassilievitch Kotchoubey, Mikhail Alexandrovitch Podust, and Olga Vassilievna’s husband Ivan Pobezhimov all fighting valiantly on the front as Artillery officers and in the mechanised units was going to succeed in driving the Germans out of Kiev and possibly out of Ukraine SSR. Nelly needed to think quickly. Her most pressing problem was how to care for her husband that had contracted tuberculosis. The symptoms were all there and she knew that any journey that they may undertake would surely kill him. Nelly had been hardened by years of hard decisions and unforgiving tragedy. Her priority now was to leave Ukraine with her daughter and find a better world for her in Europe where her brothers and many of her cousins had settled. She was faced with the awful decision of leaving her husband or risk loosing the chance to retreat with the German army.

Within the ranks of the retreating German army who were stationed in Kiev were a number of white Russians who she would have certainly been able to meet. These include count Nicholas Cheremeteff and count Bobrinsky. However, the decision to leave with through German occupied territory was a logistical challenge was it included a number of women and their children, all of whom traveled under the Wickberg name. The women included Nelly and her daughter Olga, and Zina with her two nieces (the daughters of Nina Wickberg (née Wickberg) who died at 29. Her sister Zina would raise Nina’s daughters). Nelly made her decision and along with her Vickberg relatives they left Ukraine for neighbouring German occupied Poland. They stayed in Poland until the Soviet army invaded and drove the Germans out. They reached Germany only after the soviets occupied Poland. The women arrived in Germany at the beginning of 1945. Nelly and her daughter remained in Germany until they moved to Brussels to stay with their Kotchoubey cousins and then made the decision to emigrate to Canada.

On her deathbad in the hospital in Hamilton, Canada, Nelly Wickberg with her family gathered around her, asked for the forgiveness of her sins. In the last hours of her life, she especially asked that her mother forgive her. Many years before, after the dark days of the Russian Civil war and in the years when Ukraine was plummeted into both a bloody class warfare and economic turmoil, her mother Pelegea developed tuberculosis. The horror of TB in the family was magnified by the death of baby Sergei, Nelly’s first husband Dmitri and her second husband. The devastation of loosing her eldest son and the fear of loosing her only surviving daughter forced Nelly to take drastic measures.

Her granddaughter, Olga Dmitrievna recalled many years later in Canada how her mother was walking near their house in Kiev in the late 1920s and a voice called out, “Barenya.” In those days of Soviet repression, a careless or intentional remark like that could end up with arrest, interoggation and a sentence to hard labor in the gulags or death. Nelly shuttered when she heard that word but could not help herself to turn around although she should have kept on walking. Before her stood a young girl whose mother had worked on the estate only a few years earlier and she recognized Nelly. The chance encounter was a small miracle as the young girl and her mother grew meager vegetables in the countryside and came to town to sell them on the street. Nelly agreed to buy some of the se vegetables and a friendship grew.

Conditions in Kiev in the late 1920s were difficult and food was scarce. More worringly, her mother had contracted TB and it was becoming increasingly difficult to care for her in Kiev. Maybe the country air would do her good. One day, she approached her new friends and arranged for her mother to live in the country with young woman in that way she could be cared for in the country and they would remain in contact when the young woman came to sell her vegetables. Pelegea passed away in the dark cold days of a December winter of complications from TB and the young woman made haste to the city to bring the news to Nelly. Olga remembered that there was no funeral service but she vividly remember as a young eleven year old girl the preparations for burial. Somehow, Pelagea’s bidy was returned back to her family and she was prepared for burial at home. With the curtains drawn and the minimal attention possible, Nelly would have said prayers for her mother but even the act of professing an Orthodox faith or the act of reciting prayers risked the attention of the NKVD so everything was done under the cover of darkness. A small coffin was made and Olga remembers bringing the body of her grandmother to the cemetary on a small sled pulled by her and her mother, Nelly in the hard packed snow that had been compressed by the cold winter of 1930. There they paid the guardians of the cemetary a few kopecks to bury the body in what may have been an unmarked grave.

Olga’s memory was already clouded with the pain of those terrible years of famine and terror in Kiev. Perhaps, Pelagea was buried at “Babyi Yar” a hallowed name for Ukrainian Jews who only a decade later would be murdered by the thousands and thrown into large ditches by the occupying German forces. Perhaps it was these repressed memories that Olga brought forward in her recounting of her grandmother’s burial but Olga remembered well the wails and cries in the night. She remembered how one of their friends and neighbors, an elderly Jewish professor was ordered to report at the central administration with his belongings. Olga remembered seeing him for the last time pushing a heavy wooden wheelbarrow full of the books that he could not part from even if it meant carrying them through the city on a wheelbarrow. So Nelly carried the memory of her mother dying in a small khutor probably not unlike the one where she was born and no family around her and only the faithful peasants to care for her in both her last days and in death. Sending her mother, Pelagea away to the country during her illness and death haunted Nelly for her whole life.

Elena “Nelly” Mikhailovna Wickberg