Currently being edited…

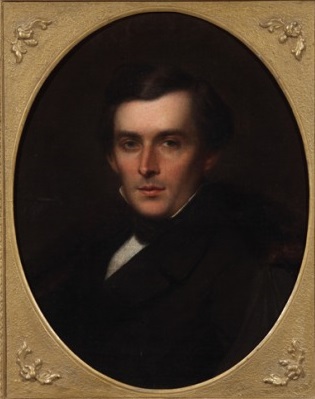

(b. Moscow, Russia 27 October 1827 – d. Venice, Italy 27 October 1865)

(b. Moscow, Russia 27 October 1827 – d. Venice, Italy 27 October 1865)

The Golden Age of Russia and the Kotchoubey Family:

Nikolai Arkadievitch was born in Moscow, into a family that had just reached the apex of its power and influence in Imperial Russia. This was a time that was known as Russia’s Golden Age and it was born of a glorious victory over Napoleon and bustling with the adoption of European culture, tastes and influence. At the time of Nikolai’s birth, his great uncle, Count Victor Pavlovich / Ви́ктор Па́влович Кочубе́й) (1768–1834) (despite the de facto title of “Bey” he was the only member of the family to accept or take an additional title of count and eventually the title of Prince in 1831) was made President of the Council of Ministers. He previously served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of the Interior. In 1834, on the eve of his death, he was also appointed Imperial Chancellor of Russia, a post that had previously been occupied by his mother’s brother Prince Alexander Andreevich Bezborodko / Алекса́ндр Андре́евич Безборо́дко (14 March 1747 – 6 April 1799). The family’s considerable wealth was rooted in Russia’s grain producing region in Malorussia (later called Ukraine) where the black earth produced bountiful harvests and its forests, much needed wood. In later years, in additional to agricultural holdings, Nikolai’s father, Arkadi Vassilievitch / Аркадий Васильевич (1790-1878), would invest heavily in railroads, while other family members would invest into the the coal seams of Donetsk. The legendary sacrifices of Vassili Leontievich only 100 years before had insured that the family would keep and grow their extensive land holdings. The family’s wealth and political influence since arriving in Malorussia in the mid 17th century had led to numerous fortuitous marriages. The Kotchoubeys quickly became the heart of a network of intermarried families that provided for favourable military and government appointments and ultimately a front row seat in Russia’s thriving cultural world, which emerged in the 1800s.

Nikolai’s father, Arkadi Vassilievitch was a soldier, a governor, an administrator, a writer and investor and Nikolai’s mother Sophia Nikolaievna (née Princess Wiazemskaya) / Софья Николаевна Вяземская) (1798-1834) was an heiress to a considerable fortune and descended from Russia’s oldest boyar families. Their marriage united four families-Kotchoubey, Tumansky, Vassiltchikov & Wiazemsky whose wealth and power was a cross section of the “who is who” in the military, political and economic corners of emerging Russia. Nikolai was the the third of five brothers, Piotr (1825-1892) Vassili (1826-), Nikolai (1827-1865) and Viktor (1828-1834), Leonti (1830), of whom only three survived into adulthood.

Nikolai’s father, Arkadi Vassilievitch was a soldier, a governor, an administrator, a writer and investor and Nikolai’s mother Sophia Nikolaievna (née Princess Wiazemskaya) / Софья Николаевна Вяземская) (1798-1834) was an heiress to a considerable fortune and descended from Russia’s oldest boyar families. Their marriage united four families-Kotchoubey, Tumansky, Vassiltchikov & Wiazemsky whose wealth and power was a cross section of the “who is who” in the military, political and economic corners of emerging Russia. Nikolai was the the third of five brothers, Piotr (1825-1892) Vassili (1826-), Nikolai (1827-1865) and Viktor (1828-1834), Leonti (1830), of whom only three survived into adulthood.

Nikolai Arkadievitch’s and the Literary world:

In his shortened life, Nikolai traveled extensively through Europe both as a private citizen and in his capacity as a member of the Russian diplomatic corps. He reached the rank of Court Councillor or VII in the Table of Ranks (Надворный советник). Coincedently, it would seem, both his marriages were to daughters of Russia’s first revolutionaries, the Decembrists. Through these and other connections, he would leave his mark in Russian literary circles through active correspondences with Russia’s most renowned writers and poets. Perhaps his most lasting legacy was bringing a thriving cultural world to the tiny village of Voronki in the province of Tchernigov whose denizens would not only build a renowned local theatre but forever link Voronki with the Decembrist movement and the fates of the Volkonskys.

Tragedy and Family Ties:

When Nikolai was still a few months old, his father Arkadi Vassilievitch was appointed Vice-Governor of Kiev (1828-1830) and in 1830, the Emperor Nicholas I appointed him Governor of the Province of Orel. In his book, A Family Chronicle. Memoirs of Arkadi Vassilievitch Kotchoubey (1790-1873) /Семейная хроника. Записки Аркадия Васильевича Кочубея. 1790—1873, which is widely used by historians today as one of the only surviving observations of the world of Orel in the 1830s (due to a fire in the 1850s that destroyed the public archives), Arkadi Vassilievitch writes extensively about the world he encounters upon his arrival. The province was a rich and bountiful region, which was also renowned as being the cradle of 19th century Russian literature. If you stand on the narrow road at the approach to the village of Kleimenovo (с. Клейменово) you can observe in a stand of trees, the recently restored cupolas of the church of the Intercession of the Holy Virigin (Церковь Покрова Пресвятой Богородицы). This is the place where the Russian poet, Afanasii Afanasovitch Fet is remembered and was buried. Today thanks to the efforts of his great grand nephew, Yourii Alexandrovitch Troubnikov, whose great Grandmother Olga Vassilivna Galakhova (née Shenshina) was the niece of both Fet (and Turgenev) there stands a small stone monument to the renowned poet in the shadow of the restored church. Before he began to undertake its restoration ,the church was was destined for ruin, abandoned in the dying years of the Soviet Union. Standing at this junction in the road a few minutes drive from the town of Orel, you cannot help but see the expanse of fields and marvel at the sky which strangely gives the impression of soaring high above one’s head and into the heavens. There are no mountains here, just endless lands of cultivated fields stretching as far as the eye can see. Suddenly, one is jolted through the events of history and one cannot help but imagine the Soviet T-37 tanks thundering through the scarred plains as their turrets swing and fire against the German’s invading panzers. Orel was also the setting for history’s bloodiest and largest tank battle which took place in 1943.

Education: Corps de Page

Nikolai spent his formative childhood years between St. Petersburg and Orel. He was educated by his father who himself had a formidable schooling. His brother Piotr Arkadievitch was two years older and also educated at home under the direction of his father and then was accepted at the Mikhailovsky Artillary School (Миха́йловское артиллери́йское учи́лище) in 1839, Nikolai left the family apartment in St. Petersburg to join the Corps de Pages (Пажеский корпус) in 1841. Like other military academies, it prepared landed hereditary noblemen for a career as officers in the regiment of their choice (subject to certain formalities). In a typical 19th century fashion, the school was governed by a strict social code of hazing and harsh conditions. This life was made tolerable by the camaraderie between classmates and the assignments as pages for ceremonial events at court. The reign of Emperor Nicholas I reached a height of military parades and uniforms with celebrations that were unparalleled in Russia’s history. The family had returned from Orel to live in St. Petersburg where Arkadi Vassilievitch was named Senator in 1842. The school was located in the imposing Vorontsov Palace which was home to the Corps des Pages. Nikolai’s heart was not set on a military career and like two of his father’s brothers, Alexander Vassilievitch and Demian Vassilievitch, who both served in the ministry of Foreign Affairs, he decided on a career in civilian service within the diplomatic corps. Upon graduating from the Corps des Pages in 1847 at the age of twenty with the rank of Gubernial Secretary (XII in the Table of Ranks / Губернский секретарь), he was being prepared for an assignment abroad in Constantinople

Before heading to St. Petersburg in 1834 and when he returned on holiday until 1837, Nikolai was often visiting and welcomed to the grand estates of Orel Province. Many of Russia’s greatest and richest families could be found here. Its proximity to Moscow also made it accesible to a large number of visitors. Not far from the city, was the estate of Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, the home of Ivan Sergeievitch Turgenev (1818-1883). who was actually born in Orel in 1818. Yasnaya Polyana, the home of the Volkonsky family which was inherited by Lev Nikolaevitch Tolstoy from his mother was also a few hours ride by carriage from the city as were the estates of the Gortchacows.

The First Decembrist Wife:

Between Orel and Moscow stands the estate of Serednikova.* The house, which stands to day is a traditional Russian manor house with a central hall flancked by two connected flegels (or wings). Ekaterina Arkadievna Stolypina / Екатерина Аркадьевна Столыпина (1824-29 March 1852) would frolic as a little school girl in her garden. Her slightly older nephew, the renowned poet, Mikhail Yurievich Lermontov (1814-1841) would spend what would become three of his most treasured and idyllic summers – 1829, 30 & 31 on the estate (see David Powelstock, Becoming Mikhail Lermontov: The Ironies of Romantic Individualism in…) surrounded by scores of his cousins and other children and all the pursuits of a country life that people carry with them when they think of a sunny day by the banks of a lazy meandering river. Ekaterina Arkadievna’s father was Arkadi Alekseevich Stolypin (b. 15 December 1778-d. 7 May 1825), a powerful political figure in St. Petersburg who was the Prosecutor General and a Privy Councillor. He was a close friend of the brilliant statesman and the father of Russian Liberalism Count Mikhail Mikhailovitch Speransky / Михаил Михайлович Сперанский (1772 – 1839) as well as the poets K. F Releev, Alexander Gribodeev and most famously his sister’s grandson, Mikhail (Lermontov). Lermontov’s grandmother was a Stolypina and this close family tie strengthened a friendship with Ekaterina’s brother Alexei Arkadievitch (1816-1858) who was a contemporary of his nephew, Lermontov and would go onto serve in the same Hussar Regiment and with whom he spent his childhood is Serednikova. As a liberal and enlightened thinker, he was linked extensively to the Decembrist movement and saved himself from the fate of other Decembrists because he died in 1825 before the actual date of the revolt on the Senate square in St. Petersburg.

Alas, Nikolai was not the only one who was attracted to the liberal intelligentsia of the day. His brother Vassili Arkadievitch married initially in 1850 a year after his brother Natalia Petrovna Saltykov and then in 1878 Maria Alexeievna (née Kapnist) / Мария Алексеевна Капнист (1848-1920) the daughter of the Decembrist Alexei Vassilievitch Kapnist / Алексей Васильевич Капнист (1796-1867)

*Serednikova was the estate where Piotr Arkadievitch Stolypin (1862-1911), Russia’s great Prime Minister grew up. Today, he is buried in Kiev’s Pechereskaya Lavra Monastery and he lies right next to Vassili Leontievitch. His Great-great Grandson, Count Peter Leontievitch Bobrinsky (1970-) is close friends with Alexander Andreievitch (1971-)

Marriage & Constantinople

Within the closed knit social world of Orel, Nikolai became a childhood friend of Ivan Turgenev who years later met and became a great admirer of Nikolai’s second wife after they went to visit him in Paris in 1858. A decade earlier, while posted on his first assignment abroad as a secretary at the Russian embassy in Constantinople, Nikolai met, fell in love and eventually married the beautiful Ekaterina Arkadievna (née Stolypina) / Екатерина Аркадьевна Столыпина (1824 -1852).

Nikolai’s father Arkadi had received a letter in St. Petersburg during the course of 1849, asking him permission to marry Ekaterina. The wedding took place in Contstantinople, Despite Arkadi’s initial misgivings as he wrote in his memoirs that Nikolai was still too young but following letters from his future daughter-in-law and assurances from his brother Alexander Vassilievitch / Александр Васильевич (1788 -1866) who had known Arkadi Alexeevitch before his death in 1825 and was a close friend, Arkadi was won over and blessed the marriage. Later after meeting her, he admitted to being impressed by her kindness and remarked on her talent for drawing. The fact that she was older than his son (by four years) led him to feel concern more for her than his son as he was concerned about his youth. For Nikolai, who was embarking on his diplomatic career and would have a life that would keep him frequently far from Russian society, the chance encounter with Ekaterina in the exotic capital of the Ottoman Porte was a blessed event. He was a young diplomat with a promising career and she was a beautiful lady whose family was well placed in the literary circles in Russia and connected by marriage to many of the grandest families at court. The two families united in a small ceremony surrounded by a small group of family memebers.

Nikolai met his future bride when she came to visit Constantinople to see her sisters Princess Vera Arkadievna Golytsina (née Stolypina) / Вера Аркадьевна Столыпина (Голицына) (1821 -1853) who was married to Prince David Feodorovitch Golitsyn / Давид Федорович Голицын (1816 -1855) and Princess Maria Arkadievna Wizemskaya (née Stolypina) /Мария Аркадьевна Столыпина (Бек, Вяземская) (1819 – 1889). Princess Vera’s husband Prince David was a member of the Russian mission to Constantinople as of 1844. He drowned tragically in 1855 while crossing the river Pron in Tambov near his estate. Perhaps, he had nothing to live for after his wife’s death two years earlier. Maria’s second husband, Prince Pavel Petrovich Wiazemsky / Павел Петрович Вяземский (1820 – 1888) was not only one of Nikolai’s distant cousins (despite Nikolai’s mother being a Wiazemsky, their common ancestor dated from the 13th century). (See: http://feb-web.ru/feb/rosarc/rak/rak-640-.htm) but also a colleague at the embassy where he was also serving as a secreatry. During her stay in Constantinople, Ekaterina was staying with her sister Princess Vera and her husband, Prince David.

Maria’s father-in-law, Prince Piotr Andreevich Wiazemsky / Пётр Андреевич Вяземский (1792-1878), was a renowned poet and both Prince Serenissime Alexander Mikhailovitch Gortchacow and Alexander Sergeievitch Pushkin’s classmate at the Tsar Alexander’s Lyceum in Tsarskoe Selo. His illegitimate sister Ekaterina Andreevna (née Kolivanova) / Екатерина Андреевна Колыванова (1780-1851) was married to the famous Russian historian, Nikolai Mikhailovitch Karamzin / Николай Михайлович Карамзин (1766 -1826).

Prince Piotr Andreevich was able to spend more time with his distant nephew Nikolai and watch from close-up courting of his daughter-in-law’s sister. Following the whirlwind engagement between Nikolai and Ekaterina the ties between the Kotchoubey-Wiazemsky family seemed to grow closer and it was further strengthened by a new marriage, albeit via the Stolypina girls. This friendship would clearly continue until Nikolai’s death and is immortalised by Prince Piotr Andreevich’s poem, “Venice” which he dedicated to Nikolai in 1863. The same year Prince Piotr Andreevich who was suffering from poor health, left Russia to settle in Baden Baden, Germany.

From 1849-1850, Nikolai was secretary at the Russian Mission in Turkey. A posting that his great uncle Prince Victor Pavlovich / Виктор Павлович Кочубей (1768 -1834) had held when he served as minister / посланник from 1792-1797. At the time that Nikolai was in Constantinople there was no appointed ambassador but the Charge d’Affaire was Vladimir Pavlovich Titov and the First Secretary was Nicholas Karlovitch de Giers the future Minister of Foreign Affairs (and married to the daughter of Princess Elena Mikhailovna Gortchacova, the sister of the Imperial Chancellor, Prince Serenissime Alexander Mikhailovitch ). This was a challenging time for Russia as it wrestled with the Eastern question and its role as self appointed protector of the keys to the Holy Sepulchre. Russian pilgrims started going to Jerusalem in great numbers in the 1840s.

Life at the mission was hectic but Nikolai’s assignement was soon over and he returned with his his young bride in 1850 to St. Petersburg where they finally met Arkadi. Meanwhile, Nikolai’s brother Vassili Arkadievitch / Василий Аркадьевич (1825-1897)was traveling through Europe with his cousin Prince Sergei Viktorovitch / Сергей Викторович Кочубей (1820 -1880). Vassili returned to Zgurovka in time fro his brother, Piotr Arkadievitch / Пётр Аркадьевич (1825-1897)’s wedding on January 14, 1851. By the time Nikolai and Ekaterina arrived in the capital, Ekaterina was expecting and careful not to attract attention to her arrival to the capital for fear that it would affect the pregnancy. In reality, she was already suffering from the 19th century euphamism for Tuberculosis or “the disease of the chest” / болезнь груди. A disease that would take her young child and many years later that of her husband. Unaware of the impending death sentence due to her illness, Nikolai prepared for his next assignment abroad and en route spent months in Zgurovka at his parent’s estate. There, Ekaterina gave birth to their daughter, Vera Nikolaivna / Вера Николаевна (1851 -1852) on April 12th, 1851. A week after the baby was born Nikolai, Ekaterina and their baby traveled to his posting to Athens, in the newly created kingdom of Greece via Odessa and the Black Sea. In three years, Europe would be at war over the the Crimea. While Russia faced its terrible destiny in Crimea, Nikolai’s happiness with Ekaterina would be short lived and he would face his own personal battle of Sevastopol in the years to come.

Nikolai, had now risen to Collegiate Secretary / Коллежский секретарь (X in the Table of Ranks). Immediately upon arriving in Odessa, their daughter Vera was christened. (see: http://odesskiy.com/chisto-fakti-iz-zhizni-i-istorii/stolypiny-v-odesse.html.) According to historical records, on 22 April 1851, in the imposing neoclassical Holy Transfiguration Cathedral of Odessa, little Vera was baptised into the Orthodox faith . Her Godparents each held a candle and watched as the priest plunged her naked body into a large vessel of holy water and after reciting the creed her godmother, Princess Varvara Nikolaievna Repnina-Volkonskaya/ княжна Варвара Николаевна Репнина turned her back to the priest and made the gesture of spitting on the devil three times. In doing so, she confirmed Vera’s newly confirmed membership in the Orthodox faith. Varvara Nikolaievna never married and she did not have children. It was said that her greatest love was the serf, Taras Grigorovich Shevchenko / Тарас Григорович Шевченко (1814-1861), who was also the fiery Ukrainian nationalist, poet and painter. Shevchenko was sufficiently close to the Repnin / Репнин family and he even painted portraits of Varvara’s niece and nephew, but he chose never to return her affections. Varvara It was perhaps for the best, as the family had suffered enough scandal during the Decembrist uprising and Varvara’s own father who was embroiled in a scandal on bribery in Poltava. Shevchenko was the object of arrest, imprisonment and exile for most of the last ten years of his short 47 year life. Shevchenko’s portrait of Vassyl Kotchoubey and his painting of Matrena Kotchoubey and her mother are among his most celebrated images of the Judge General and his family in Ukraine today. The portrait of the Judge General was commemorated with a stamp issued in 2014 by the Ukrainian government. Little Vera’s godfather, who stood by Varvara as she recited the creed, was Ekaterina’s first cousin Valerian Grigorievitch Stolypin / Валериан Григорьевич Столыпин.

Репнина-Волконская (княжна Варвара Николаевна, 1809 – 1891) – дочь предыдущей, писательница, фрейлина; поместила в “Русском Архиве”: “Из воспоминаний о прошлом” (1870), “О совращении иезуитами княгини Воронцовой” (1870), “К биографии Шевченко” (1887, II), “Встреча с Императором Александром I в 1819 году” (1888, II), “Из воспоминаний о Гоголе” (1890, III) и “Воспоминание о бомбардировке города Одессы в 1854 году” (1891, III). Ранее, в 1840-х и 1850-х годах, Р. писала под псевдонимом Лизверской; из ее произведений этого периода наиболее были распространены “Советы молодым девицам”. Р. была в переписке с Гоголем и Шевченко , выразившим свое сочувствие к ней в стихотворении “Тризна” (1843). Переписка Р. с Шевченко, главным образом, ее письма за 1844 – 1845 годы, являются почти единственным материалом для биографии поэта за это время. См. “Шевченко в переписке с разными лицами” (“Киевская Старина”, 1897, № 2) и граф С. Шереметьев “Княжна В.Н. Репнина” (Санкт-Петербург, 1897). (Source: http://www.rulex.ru/01170039.htm)

The stay in Odessa gave the young family a chance to rest and especially Ekaterina who was now weakned by her cancer and trying to take care of her newborn. In Odessa, the family stayed with the Repnine-Volkonsky family which unbeknownst to Nikolai would many years later figure among his new relatives both through his second marriage and his brother Piotr’s marriage to Varvara Alexandrovna (née countess Kushelev-Bezborodko) / Варвара Александровна Кушелева-Безбородко (1829 -1894) in 1851. Odessa was a city that had strong ties to both families but especially Ekaterina’s family since her grandmother, Henrietta Alexandrovna was the sister of Englishman Field Marshall Thomas Cobley / Томаса Кобле (Cobley) , the Commandant of Odessa during the Napoleonic wars and a londowner of an estate called Cobleyevka. He was already a legendary figure in England and travelers would make a point to visit the eccentric Englishman who became a Russian officer and subsequently a mayor and all the while a passionate landowner. Odessa, afterall was home to a large English community in the early 19th century.

From Odessa they sailed onwards through Constantinople, the city where they had fallen in love and then onto Athens. The posting in Athens began in the Fall of 1851 and in their brief time in the capital, Ekaterina was showing more signs of consumption. Nikolai decided that he must leave his post in Athens to accompany his wife to Italy for treatment. at the begining og 1852, they traveled to Italy and there destination was Pisa with the thought that a change in climate would help her condition. Tragically, Ekaterina Arkadievna died there at the age of 28 on March 29th , 1852. The tragedy was made more cruel by the fact that Pisa was the city where many years before, her English grandmother, Henrietta Alexandrovna Mordvinova (née Cobley) / Генриетте Александровне Кобле (1764 — 1843) whose father was an English aristocrat and a wealthy merchant as well as the English Consul in Livorno met her husband, Count Nikolai Semienovitch Mordvinov / Никола́й Семёнович Мордви́нов (1754-1845) and fell in love and began her Russian adventure. 2 The connections with the Kotchoubeys and the Mordvinovs do not end there. Not surprisingly, in the narrow world of the ruling elite, Admiral Count Nikolai Semionovitch was a friend of Prince Viktor Pavlovitch and together, in the early 19th century they chaired the committee on the Creation of the New Russia Province / комитет «Об устроении Новороссийской губернии. Prince Victor Pavlovich owned a large estate called Mukhalta near Yalta and while the property was ransacked by the French in 1855 during the Crimean War, it remained in the family until the end of the 19th century when it was sold to a wealthy Russian merchant.

With Ekaterina’s death, Nikolai was inconsolable. Still a young man he made the terrible journey from Italy to St. Petersburg with the body of his beloved wife. As if to complete the cycle of tragedy, only a month later after the trip back from Italy to St. Petersburg, Nikolai suffered another blow when his infant Vera fell ill and died on 21 April 1852 probably from tuberculosis, too.

It was a journey that would become all to familiar to the family who in the ensuing years would bring many more members of the family back from Italy to be interred in their native Russia. While preparing to bring them home for burial he ordered a beautiful monument in marble grant and steel to be made by the renowned Florentine sculptor Aristodemo Costoli. The winged angle in marble praying to the heavens for his wife and daughter was erected in St. Petersburg’s Alexander Nevsky’s Lavra cemetery four years after their 1852 burial in 1856. In the way his father before him, erected a chapel to the lost members of the family in Orel, Nikolai’s tombstone which stands today, is a testament to the devastating loss of a beloved child, a beloved wife and happiness that was torn from him too early.

After the funerals in the spring of 1952 in St. Petersburg, Nikolai returned to Athems and he threw himself into his work. His father had been a supporter of Greek Independence in the tumultuous year of 1830 and in the 1850s, Nikolai could carry the pan-orthodox support that was prevalent in Russia to his service as first secretary at the Russian embassy in Athens, Greece. The ambassador was Ivan Emanuelevitch Persiani / Иван Эммануилович Персиани (1790-1888).

Voronki, A Kotchoubey Estate again:

In 1850, Arkadi Vassilievitch bought an estate for Nikolai and Ekaterina as a wedding present. The other estates in the family would remain in Arkadi’s possession and eventually passing to Nikolai’s surviving brothers, Vassili & Piotr. Piotr as the eldest would inherit the family seat of Zgourovka which had been in the Wiazemsky family and part of his mothet’s dowry.

Voronki (Вороньки (Черниговская область) is a village and at the time was an estate which is located in the southern part of the Tchernigov province. It is north of Kiev in what today is called the Bobrovitskiy Region. It is characterized by its proximity to the slow moving Supoi river. Even today, it is renowned for its unspoilt beauty and incredible nature.

In 1782, the village became the property of the wealthy and powerful Miloradovich family and more specifically, Grigori Petrovich Miloradovitch (1765-1828) who retired with the rank of Captain from military service in 1786. The following year, in 1787, he married Alexandra Pavlovna (1769-1838), the sister of Victor Pavlovich (he had not yet accepted the first of two titles and so is not yet referred to as count or prince) who as a friend of the young Tsarevich Alexander Pavlovich was already a member of the Secret Committee and a valued and respected Russian diplomat in Europe. Together the couple would have thirteen children. Perhaps because of the connections that his marriage to Alexandra could provide or in keeping with the strong family ties that existed between relatives of the Miloradovitches and the Kotchoubeys, Grigori’s weak health led him to the diplomatic service where he would work with his brother-in-law, Victor and for his relative Prince Alexander Andreevich Bezborodko. Eventually Grigori Petrovich was appointed among other roles as Judge General of Malorussia (Ukraine) in 1797. One of his sons inherited the village and then sold it to Nikolai Arkadievitch, a cousin and a beloved member of a broader family now serving Russia both at home and abroad as a diplomat.

The land is characterized by vast fields punctuated by stands of pine trees and birch trees which are separated by meandering rivers and streams and beautiful lakes. The village which has just over 1000 inhabitants today is of little historical significance except that the Kotchoubeys lived there and the Decembrist, Prince Sergei Grigoriovitch Volkonsky and his wife, Princess Maria Nikolaivna (née Raevskaya) both died and were buried on the estate. There is a contemporary commemorative monument to them and their fellow exiled Decembrist, Alexander Poggio but the original chapel designed by Alexander Yagn to mark their final resting place and their gravestones were destroyed in the 20th century.

The Second Decembrist Wife: “We’ll always have Paris”

The Russians first arrived in significant numbers to Paris in 1814. Among the Russian officers to have occupied Napoleon’s capital were Arkadi Vassilievitch and Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonski and they were among the elite Russian officers who led the delicate negotiations with Napoleon’s marshals on behalf of the Russian Emperor Alexander I, due to their excellent commande of the French language.

In a book about the history of Russia’s aristocrats in Paris entitled, Saint-Alexandre-Sur-Seine by Nicolas Ross there is a wealth of information regarding the extent to which this storied introduction to Paris and broadly to France which began in earnest in 1814 grew in the 19th century. Both the Kotchobey and Volkonsky family were among the Russian francophiles to not only visit France, but build and purchase homes there and ultimately settle in their adopted country after the Russian revolution. It was an unforeseen consequence to the act of patriotism that was rooted in the liberation of Paris in 1814.

From the archives of the cathedral of St. Alexander Nevski which was consecrated in 1861 and located on the rue Daru in Paris, we learn that from 1817 until 1858 in the Russian Orthodoxe chapel on today’s rue de Berri, of the 168 baptisms that were registered, 66 of them were children of the Russian aristocracy, and 44 of the 97 marriages performed were members of the Russian aristocracy. The baptismal and wedding register in the archives of the catjedral goes a long way to explain that the Russian aristocracy not only had the means to travel to France but they were keen proponents of laying down some sort of roots with their adopted second country, France for their most important events.

In 1858, on his return from Athens Greece, Nikolai met Elena Sergeievna “Nelly” Molchanova (née Princess Volkonsky). By September 22nd, 1858 they were announcing their engagement and it was clearly love at first sight.

We learn from a number of sources that both the Kotchoubey family and the Volkonsky’s had plenty of reason to choose Paris as a destination for the wedding. Perhaps, the most influential factor in the decision to travel to Paris was that Nelly’s mother, Princess Maria Nikolaievna (née Raevskaya) /Мария Николаевна Раевская (Волконская) (1805 -1863) was receiving medical treatments in Paris for problems with her liver which she developed in exile in Irkutsk. Only the year before in 1857, Nikolai’s brother Vassili Arkadievitch / Василий Аркадьевич Кочубей (1826-1897)who was married to Natalia Petrovna (née princess Saltykova) / Наталья Петровна Салтыкова (1829-1860) in 1852 celebrated the christening of his second son, Piotr Vassilievitch (1853-1879). Vassili and Natalie met at the home of Piotr Arkadievitch in the year following his wedding to Varvara in 1851. Natalia was a lady in waiting to the Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna. The church records show that on June 1857, little Piotr was christened and the that the godparents were little Piotr’s grandfather, Prince Peter Dmitrievitch Saltykov / Пётр Дмитриевич Салтыков (-1889) and princess Sophie Radziwill. Like many Russian aristocratic families, the Saltykovs were fascinated by France and had begun to establish themselves in the capital and intermarry into the French aristocracy and nothing exemplified this move as the marriage between Prince Piotr Saltykov and his second wife, Henriette Charlotte Dufourc d’Hargeville whom he married in Paris 10 years later in 1868. His son, Prince Ivan Petrovitch Saltykov / Иван Петрович Салтыков (1831-1906) managed to follow his father and married a year before his death in 1905, Améelie Valentine Mestre (1860-1940).

The links were not limited to the Saltykovs as two sons of Prince Viktor Pavlovitch / Виктор Павлович Кочубей (1768-1834) were establishing themselves in France for different reasons. His son, Lev Victorovitch / Лев Викторович Кочубей (1810 -1890) was splitting his time between government obligation in the Poltava region and France. He was actively involved in the French horticultural society and even had a rose name in his honor which is known as the Prince Leon Kotschoubey rose. He was married to a distant cousin, princess Elisabeta Vassilievna (née Kotchoubey) / Елизавета Васильевна Кочубей (1821-1897) and the eventually settled in Nice, where they both passed away at the end of the 19th century. His younger brother prince Mikhail Viktorovitch / Михаил Викторович Кочубей (1816-1874) married shortly after the death of his first wife, Maria Ivanovna (née princess Bariatinskaya) / Мария Ивановна Барятинская (1818-1843), to a French noble whose family were in the theater and her name was Marie Alice de Bressant (1838-1909). With the arrival of more Kotchoubeys in Paris, Lev Vicotorovitch and his wife Elisabeta Vassilievna were sure to join the festivities.

1858 was a busy year for the family in Paris as in January 1858, princess Marie Alice is chosen as the godmother of prince Piotr Troubetzkoi along with fellow godparents, prince Constantin Belosselski-Belozersky and princess Alexandra Troubetzkoy.

In Ocotber 1858, the family gathered at the Russian Orthodox chapel on the due de Berri . The official witnesses at the wedding were Nikolai’s father, Arkadi as well as Nikolai’s second cousin count Gregory Alexandrovitch Stroganov / Граф Григорий Александрович Строганов (1824-1878) who was married marganaticlly to Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (the daughter of Emperor Nicholas I) and was the son of countess Natalia Viktorovna (née princess Kotchoubey) / Наталья Викторовна (1800-1855). In addition, Elena’s father Prince Sergei Grigorovitch and count Grigory Alexandrovitch Kushelev-Bezborodko / Григорий Александрович Кушелев-Безбородко (1832-1870) completed the officials witnesses who signed the registry. Kouchelev-Bezborodko, a publisher and editor who was closely associated to the University of Nejin which was founded by his family had the dual role of representing both the bride’s and the groom’s family as his mother was prince Sergei Grigoriovitch’s niece princess Alexandra Nikolaivna Repnina-Volkonskaya / Александра Николаевна Репнина-Волконская (1805-?) and his sister Varvara Alexandrovna (née countess Kusheleva-Bezborodko) / Варвара Александровна Кушелева-Безбородко (1829 -1894) was married to Nikolai’s brother Piotr Arkadievitch / Пётр Аркадьевич (1825-1892). The Kushelev-Bezborodko’s were also cousins of prince Viktor Pavlovitch as his mother was also a Bezborodko.

Only the year before, Counte Gregory Alexandrovitch had also been married in Paris at the chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul. The wedding on November 26th, 1857 was scandalized by the sheer cost of the wedding and the size of the wedding party which arrived from St. Peteersburg. Count Gregory arrived with a suite of 32 people and his bride wore a dress that was said to cost 20,000 rubles. He had organized a ball for 150 people, inviting questionable people and all according to one eye-witness, Paul Durnovo (who was also to marry a Kotchoubey) who suggested that this display of ostentatiousness was to impress his mistress who was about to become his wife, Lubov Ivanovna Kroll /ЛЮБОВЬ Кроль (-1870). The wedding and ultimately the marriage, scandalized St. Petersburg society and it pushed Count Grigory out of the aristocratic social circles into the literary world who he would ultimately champion by publishing and support through his work as an editor.

The marriage was amazing in so many other ways as it brought together two families whose patriarchs were long ago friends. Nikolai’s father Arkadi and Elena’s father, Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonsky / Сергей Григорьевич Волконский (1788 -1865) were schoolmates and served in the Napoleonic wars together. The wedding was immortalized by a series of photographs (now kept at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, France) by the renowned photographer of the time, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819 – 1889). While the Volkonsky’s travel schedule was complicated by , the family nonetheless traveled to Italy, while the honeymoners took a stop in Venice where they would have visited Nikolai’s cousin, Prince Sergei Viktorovitch / Сергей Викторович Кочубей (1820 -1880) and his second wife Sophia Alexandrovna (née countess Benkendorff) /Софья Александровна Бенкендорф (Демидова, Кочубей) (1825-1875). Upon returning home to Nikolai’s estate, Voronki, they would soon welcome their first son Alexander Nikolaivitch (1859-1861).

Elena Sergeievna, known for most of her life as “Nelly”, was the daughter of Sergei Grigorievitch Volkonsky the towering figure of the Russia’s Decembrist movement, (he was officially stripped of his title, Prince, and all his lands by the Tsar following his trial and condemnation for participating in the Decembrist revolution of 1825 so technically should not have the use of his title). She was born and raised in Irkutsk, Siberia during part of her parents’ exile. Her mother was Maria Nikolaievna Volkonsky (née Raevskaya) the indominatable daughter of the hero of Borodino Nikolai Nikolaievitch Raevsky and a muse to Alexander Pushkin who may have dedicated as many as 6 poems to her.

Sergei and Maria Volkonsky were liberated from their Siberian exile by Alexander II in 1856, soon after his father, Nicholas I’s death and in the first year of his reign. The family left Irkutsk and traveled immediately to MaloRussia along with other exiled Decembrists and on to Paris, Switzerland, Rome and they were accompanied by their daughter Elena Sergeievna and her new husband Nikolai Arkadievitch. Nelly’s mother Maria Nikolaievna left for Paris to be treated for liver disease and on the heels of the engagement, the whole family, including Sergei Grigorievitch rushed to Paris to be with her. (see: Engagement Announcement and Departure for Paris) During their visit, the family and their relatives sat for the Parisian photographer in 1858 and their visit is captured in a collection of photographs that are now at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. When in Paris, Nikolai introduced Nelly to his friend, Ivan Turgenev. Her childhood was anything but conventional and her subsequent return to European Russia with her parents was the beginning of a new chapter in the Volkonsky family and one that would be intertwined with he Kotchoubeys into the 21st century.

Maria Nikolaievna had a passion for the theatrical arts was not incidental. Princess salons in her home in Irkutsk were renowned for their focus on music, literature and philosophical debates. She along with her husband both wrote their memoirs, while Prince Sergei Grigoriovitch wrote a number of additional works. When Princess Maria Nikolaievna joined her daughter at Voronki from Siberia, she set about building a theater and introducing an important artistic tradition that would last until the revolution.

The young heir was born in Voronki. It was an idyllic time for the family who together with the Volkonsky parents-in-law set about establishing themselves on the beautiful estate. Tragedy struck again for Nikolai and his young son, Alexander died in 1861 at the tender age of three. He was buried in the church at Voronki and a few years later his grandmother, Princess Maria Nikolaievna Volkonskaya would be buried in the crypt next to him. In 1863, their som Mikhail (Mikhailo) was born and he became his only surving son Nikolai was to see little of his second son as he was already marred by failing health which took a turn for the worse by a 1864. The following year he dies in Venice of Tuberculosis.

In a letter to his sister-in-law Sergei Grigorievitch writes in French (see: Letter Announcing Mikhail’s birth) :

11, January 1863, Voronki

To: A.M. Raevskaya,

If I am late, dear esteemed sister, to announce Nelly’s pregnancy, this is not forgotten, but we are happy to announce the happy event snd I wanted to assure you of her state. Here we are in the 6th day and in tranquility for both the mother and the baby, whose name is Michel.

Years later, Lev Nikolaeivitch would vist his cousin Elena Sergeievna on her estate as he would be tormented by his unfinished novel, the Decembrists.

was a world that years later would bring Lev Nikolaievitch to vist his cousin Elena Sergeievna on her estate as he would be tormented by his unfinished novel, the Decembrists. Within the closed knit social world of Orel, Nikolai became a childhood friend of Ivan Turgenev who years later introduced him to his second wife Elena Sergeievna. That year was 1858 and it was love at first sight. They married that year and soon welcomed their first son Alexander Nikolaivitch (1859-1861) who was born in Voronki. It was an idyllic time for the family who together with the Volkonsky parents-in-law set about establishing themselves on the beautiful estate. Tragedy struck again and young Alexander dies in 1861 at the tender age of three. Mikhailo would become their only surving son after he is born in 1863. This was bittersweet year as the cycle of death and birth was fulfilled with the death of Mikhail0’s grandmother, Maria Nikolaievna who diedon August 10th after a long illness. The joy of his birth is already marred by Nikolai’s health which takes a turn for the worse as he begins to show obvious signs of Tuberculosis.

Nikolai left Ukraine and Voronki to live in a more humid climate with the hope that he might delay the inevitable. The last years of his life were spent in Venice and he nonetheless succumbed to tuberculosis in 1865 on his birthday, 27 October. His wife, son and family were in Russia. He died in the company of his faithful servants, his cousins and friends but he died never to see his beloved Voronki again.

Nikolai last years were spent in the Kotchoubey palazzo with its beautiful garden located on the Dorsoduro overlooking the Guidecca Canal. The palace in Venice which passed through the family for only a brief period was purchased by Nikolai’s second cousin, Prince Sergei Victorovitch / Сергей Викторович Кочубей (1820 -1880) and his wife Princess Sophia Alexandrovna (née countess Benkendorff) /Софья Александровна Бенкендорф (Демидова, Кочубей) (1825 -1875). It was perhaps through Princess Sophia’s first husband, Pavel Grigorovitch Demidiov /Павел Григорьевич Демидов (1809 -1858), a member of the fabulously rich industrialist family and a cousin to Anatoly Nikolaievich Demidov, 1st Prince of San Donato / Анатолий Николаевич Демидов; (1813 -1870) who was a great patron in Italy and for a brief time a diplomat in Venice that the palace came into their possession.

That year, Nelly accompanied by the aging Decembrist, Alexander Poggio, traveled to Venice to bring her husband’s body back to Voronki. A funeral service was held at the Orthodox church of San Giorgia dei Greci.

Poem by Prince Piotr Andreevich Wiazemsky written and dedicated in 1863 to Nikolai Arkadievitch Kotchoubey:

Николаю Аркадьевичу Кочубею

Венеция прелесть, но солнце ей нужно,

Но нужен венец ей алмазов и злата,

Чтоб всё, что в ней мило, чтоб всё, что там южно,

Горело во блеске без туч и заката,

Но звёзды и месяц волшебнице нужны,

Чтоб в сумраке светлом, чтоб ночью прозрачной

Серебряный пояс, нашейник жемчужный

Сияли убранством красы новобрачной.

А в будничном платье под серым туманом,

Под плачущим небом, в тоске дожденосной

Не действует прелесть своим талисманом,

И смотрит царица старухой несносной.

Не знаешь, что делать в безвыходном горе.

Там тучи, здесь волны угрюмые бродят,

И мокрое небо, и мутное море

На мысль и на чувство унынье наводят.

Под этим уныньем с зевотой сердечной,

Другим Робинсоном[1] в лагунной темнице,[2]

Сидишь с глазу на глаз ты с Пятницей[3] вечной,

И тошных семь пятниц сочтёшь на седмице.[4]

Тут вспомнишь, что метко сказал Завадовский,[5]

До прозы понизив морскую красотку:

«Здесь жить невозможно, здесь город таковский,

Чтоб в лавочку сбегать — садися ты в лодку».

27 октября 1863

Венеция

A Web of Family Relations:

The Bezborodko, Repnine factor

At this juncture, we need to look back into some important historical events that would come winding its way into the cozy world of the Kotchoubey-Wolkonsky marriage like Japanese knotweed which once rooted in a garden seems to become a constant companion to the plants, even suffocating them. Years before, two importnat people and one important event would play a role unbeknownst to them in the fate of Elena Sergeievna’s stay in Voronki. The first is the Chancellor Alexander Bezborodko among many august roles he was responsible for Ukraine under Catherine II and he took upon himself the responsibility of raising young Prince Viktor Pavlovich (1768-1834) and his brother who were both left fatherless at a young age. Viktor Pavlovich who was married to Princess Maria Vassiltchikov in turn raised Mikhailo’s grandfather Arkadi Vassilievitch (1790-1878) and one of his brothers when they, too lost their father in 1800 when Arkadii was only 10 years old. Certainly due to the close relationship to Prince Viktor Pavlovich’s family and the years spent in their company, Arkadi’s met his wife at an a ball in St. Petersburg who was the daughter of Princess Vassiltchikova. This must have overjoyed the Prince and Chancellor Viktor Pavlovich and his wife who would proudly watch both their nephews embark on a long illustrious path in governement service and would become an important mentor the family. Bezborodko died childless but his fortune passed to his nephew and eventually his great grand niece would marry Piotr Arkadievitch. A secondcloser figure was Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonsky. He was, of course Mikhailo’s grandfather. Year earlier several important moments took place. Firstly, Prince Sergei’s mother was the last of the powerful and storied boyar family, the Princes Repnine. Emperor Alexander I proclaimed that Prince Nikolai Grigorovcitch, Prince Sergei’s brother would carry his mother’s name and he became Prince Nikolai Grigorovich Repnine-Volkonsky. childles The relationships within the small world of the family were further complicated by the fact that Piotr Arkadievitch was married to Barbara Alexandrovna (née Kushelev-Bezborodko) whose mother Alexandra Nikolaevna (née Princess Repnina-Volkonskaya) was Elena Sergeievna’s first cousin. The family ties aside, there was concern on the part of the Kotchoubey’s about the amount of money that Elena Sergeievna was spending and in addition she had decided to marry a third time, a minor landed nobleman who was also Voronki’s estate manager, Alexander Alekseevich Rakhmanov (b. 1830 – d. 23 December 1916) (Александр Алексеевич Рахманов). He was probably related to Varvara Nikolaevna (née Rakhmanova (Варвара Николаевна Рахманова) (?-1846) who was married to Nikolai & Piotr Arkadievitch’s uncle, Vassili Vassilievitch. It was decided, most likely by Piotr Arkadievitch that they would buy her Veisbokhovka which was 30 km away and next to Varvarovka, another Kotchoubey estate. This would isolate her spending activities into a manageable quantity and allow her to build a home separately with her new husband. What ever the distances,

Notes:

Sources:

1. http://odesskiy.com/chisto-fakti-iz-zhizni-i-istorii/stolypiny-v-odesse.html

2. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Мордвинов,_Николай_Семёнович