b. Voronki, Tchernigov Province, Russia 1889 – d. November 15th 1920. Died at Sea near Sebastopol during the evacuation of Crimea aboard destroyer “Zhivoy” which went down in a storm.

Vassili Mikhailovitch was the son of playwright, Mikhail Nikolaievitch (1863-1935) and a local beauty, Pelegea Dmitrievna (née Onoshko) / Пелагея Дмитрьевна Онощко (1863-December 19, 1930). In addition to her legendary beauty, she would become recognized for being the driving force behind the success of Voronki as a commercial enterprise and remained in the village until her death in 1930. Sergei’s father abandoned the family and Russia in the years after civil unrest in Ukraine, in 1913. He departed for France where he died on the Cote d’Azur in 1935.

Vassili was born on his Grandparents’ estate (Nikolai Arkadievitch and Elena Sergeievna (née Princess Volkonskaya) that was called Voronki (Вороньки (Черниговская область). The estate is located in the southern part of the Tchernigov province which is north of Kiev (today Bobrovitskiy Region) on the banks of the Supoi river. Even today, it is renowned for its unspoilt beauty and incredible nature. As of 1782, the property belonged to the Miloradovich family who had married into the Kotchoubey family in the early 18th century. It was purchased by Arkadi Vassilovitch for his son Nikolai in 1850. The land is characterized by vast plains punctuated by stands of pine trees which are separated by meandering rivers and beautiful lakes. Its historical significance today is largely due to the facts that the Kotchoubey’s lived there and the fact that the Decembrist, Prince Sergei Grigorovich Volkonsky and his wife, Princess Maria Nikolaivna (née Raevskaya) both died and were buried on the estate. There is a contemporary commemorative monument to them and their fellow exiled Decembrist, Alexander Poggio but the original chapel designed by Alexander Yagn and gravestones were destroyed in the 20th century.

Today this region is in Ukraine, and for 400 years it was part of a geographic region that was historically tied to the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The first Kotchoubeys to arrive in the region in the early 17th c. settled in and around Baturyn, which at the time was the capital of Tchernigov. The family played an important part in the history of this illustrious Cossack host, Imperial Russia and establishing Ukraine’s brief independence under the last Hetman before the rise of the Soviet Union.

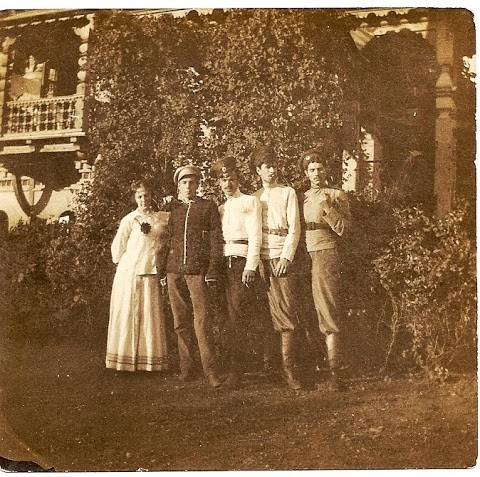

Vassili was the eldest of four brothers, Vassili, Nikolai, Mikhail & Sergei and one sister, Elena “Nelly.” Nikolai was educated at home until he was sent, like other young noblemen, to St. Petersburg in 1897 to study at the Nikolaevskiy Kadetskiy Corpus (Николаевский кадетский корпус) located at 23 Ofitserskaya Ulitsa. The Corpus was a military school and more comfortable then other similar schools. He benefited from various creature comforts which included the presence of servants.

While the Kotchoubeys preferred to be near their estates in Ukraine, at the time of Vassili’s schooling in St. Petersburg, many members of the family were at Nicholas II’s court. Nikolai’s distant aunt, Princess Elena Konstantinovna (née Beloselsky-Belozersky) (Елена Константиновна Белосельская-Белозерская (Кочубей) р. 1869 ум. 1944) was a lady in waiting to the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and her husband Lt. General Prince Sergei Viktorovitch (Виктор Сергеевич р. 1860 ум. 1923) was a close friend and an aide-de-camp to Nicholas II. He accompanied him on to tour of Asia including Japan when Grand Duke Nicholas was still Tsarevitch. Prince Sergei and his wife, were the last owners of the famed Dikanka palace in Poltava. Yet another uncle, Vassili Petrovich, a Guard’s officer was to be named Master of Ceremonies & Kamer-Junker (камер юнкер) of the Imperial Court in 1912.

Marriage and A Young Family:

Vassili returned to the estate to manage affairs in the wake of his father’s abrupt departure for France. He fell in love with Ludmila Alexandrovna (née Podust) / Подуст Людмила Александровна (17.06.1889– 2.06.1984). Two children were born from this happy union, Olga Vassilienva / Ольга Васильевна (b. Voronki, Russia 19 April 1911- d. 2 May 1982, Saratov, USSR) and Georgi “Zhorzh” Vassiliovitch / Георгий Васильевич (b. Voronki, Russia, 6 October 1915- d. 13 November 1996, Saratov, Russia). While the young children would enjoy an idyllic childhood at Voronki it was not to last. When Vassili’s regiment joined Denikin’s white army, Ludmilla and her children would remain for a while in Kiev but then in the 1920s without any news of Vassili they would move to Saratov and join her family.

The Voluntary Army under Gen. Anton Denikin

As did his brother, Nikolai after him, Vassili went on to study at the Elizabetgradskoe Cavalerskoe Uchileshe ( Елисаветградское кавалерийское училище ). He graduated on July 12th, 1914 as a 1st ranked Junker Kornet / 1-й разряд, из юнкеров корнетом . (see: http://regiment.ru/reg/VI/C/18/3-5.htm). Graduates of both the Korpus and the Uchilishe were destined to serve in cavalry units and the Kotchoubeys were no exception. While two branches of the family would serve in the Chevalier Guard reginement (Кавалергардский полк) , Vassili was commissioned an officer in the illustrious 11th Izumskiy Hussar regiment of Gen. Dorokhov formerly His Royal Highness Prince Henry of Prussia (11-й гусарский Изюмский генерала Дорохова, ныне Его Королевского Высочества Принца Генриха Прусского полк) just on the eve of it being renamed simply the 11th Hussar Izumsky Regiment of Gen. Dorokov / 11-й гусарский Изюмский генерала Дорохова полк in August 1914. The regiment was among the oldest Russian regiments (1651) in Russia whose roots were to be found in the cossack regiments that emerged from ‘Malorus’ (the pre-revolutionary name for Ukraine).

Vassili fought with his regiment from the beginning of WWI. The Hussars entered Austria in 1914 and they would fight their way into Romania to defend against the Austrians who had routed the Romanian army in early January 1917. By spring, as the regiment moved up toward Galicia, their responsibility was diverted from engagements on the front and more towards hunting down and arresting deserters. This focus, would continue in Denikin’s army under the OSVAG department where Nikolai and his brothers worked on pursuing and detaining Red agitators.

At the beginning of 1918, officers and members of the disbanded Izumskiy Hussars, which had ceased to exist in October 1917, reformed their ranks under the command of the Hetman Skoropadskiy and was renanmed the Ukrainian 9th Iziumskiy Cavalry regiment and in September 1918, General Anton Denikin, personally received the old standard of the Hussar regiment and it officially came under his command. Sergei along with his brothers had now joined the Voluntary Army. It was November 1918. The brothers were put to work in the intelligence operations of the White Army and served in the OSVAG (office of the Russian Press). They were involved in highly classified missions throughout 1919. Following Denikin’s defeat in 1919 and his retreat to Crimea, Nikolai and his brothers would serve under General Pyotr Wrangel.

Evacuation from Crimea and Disaster:

When Baron Piotr Wrangel took over the government of Southern Russian on the Crimean peninsula in March 1920 he knew that the most likely outcome of the effort to build a Russian government was failure and a forced evacuation from the peninsula and work began immediately for this potential outcome in March 1920. A number of insights emerged from a conversation with French historian and authority on Wrangel, Nicolas Ross, at the Salon du Livre on 30.04.2105 on the occaision of a presentation of his book, La Crimée blanche du général Wrangel. While some early victories for the White Army forces in the South suggested a certain momentum towards positive stabilization a number of negative factors could not be mitigated.

Firstly, the population of the Crimea with over a million inhabitants and several hundred thousand refugees did not have the economic base to feed its population. A move outside the peninsula to secure arable land in the Tauride was essential to insure the supply of food. Supported by a strong airforce that had emerged from WWI in suprinsingly good shape, helped to turn back the Bolshevik army in the middle of 1920, however, the early onset of winter and the freezing over of a key geological water barrier allowed the Red forces to transport artillery pieces into the Crimean Peninsula and turn the tide of the war.

Secondly, while Wrangel had begun preparations for an evacuation in early 1920, he had not provided enough ships to evacuate all the officers, their families and the refugees who found themselves in Crimea. Initial estimates were for 70,000 people but by November 1920, it was over 145,000 thousand. Wrangel was an officer and he never pretended to be a politician. Unlike many of the Tsarist Generals who plotted to seize control of the Russian Government in a hope of stemming the rise of Bolshevik power, Wrangel retired in 1918 and was already en route to Serbia when he was recalled into service for the White cause. As such, Wrangel was a pragmatist and a realist and this trait alone was probably the single biggest factor in saving the lives of som many White officers and refugees who found themselves in Crimea in 1920. Realizing that he did not have enough ships to carry all the people he ordered his adjutant, vice Admiral Mikhail Aleksandrovich Kedrov / Михаил Александрович Кедров, (1878–1945) to undertake the task of finding additional ships and this would then become the famous Wrangel fleet which traveled from various ports in the Crimea to Turkey and then on to Bizerte where the remaining ships that were not scuttled would be sent off to the various European navies. The command of this fleet was then given to Admiral Mikhail Andreievitch Berens / Михаил Андреевич Беренс (1879 – 1943). The ships would depart from the following ports: Sebastopol, Yevpatoria, Kerch, Fedoisa and Yalta.

Thirdly, Wrangel unlike his predecessor General Denikin did not espouse a policy of one army, one Russia which effectively alienated many of the emerging states within Russia’s collapsing empire, including Poland, Belorussia, Ukraine, The Cossack states of the Kuban, Don, Astrakhan and Terek and the Caucuses. As such, Wrangle, not only engaged in a charm offensive through his emissaries to recognize the ambitions of all these fledgling states but engaged in discussion with the European powers to secure some sort of dialog and eventually recognition. While the English helped to evacuate the remaining members of the Imperial family and members of court along with their relatives and retinue of staff, the offcial government line was to force the White movement to sue for peace with the new Bolshevik government. A recommendation that if it had been followed would have lead to the death of hundreds of thousands of Russians. The French government did not recognize the Government of Southern Russia per se but Wrangel offered to recognize Russian Imperial debts in proportion to the Crimean’s overall place within Russia’s historical borders. For the French bond holders which included the French State and who were among the largest investors in Russia, this was a welcome opportunity to secure some recourse on debt that would likey remain in default following the revolution of 1917. The government of Southern Russia only was able to speak to the equivalent of 1% of the overall debt value but this was enough to insure a dialog between the two parties and the French were a critical factor in the evacation of the Crimea.

Refering to an online article by A. I. Ushakov (see: White Army Evacuation (in Russian)), the Kotchoubey brothers and their wives with the exception of Vassya whose wife and children remained all traveled with the 1st and 2nd Army and Cavalry Corps which was commanded by Lt. General Ivan Gavrilovotch Barbovitch / Иван Гаврилович Барбович (1874-1947).For the Kotchoubey brothers, the General was not only a neighbor from Ukraine but finished the same school as then amd was ultimately Nikolai’s commanding officer. Like Vassya and Nikolai, General Barbovitch finished the Elisavetgardskiy Cavalry Junker School / Елисаветградское кавалерийское юнкерское училище but in 1986 and then was immediately commissined a cavlry officer in the 30th Dragoon Ingermanlandsky regiment which in 1907 became the 30th Ingermanlandsky Hussars Regiment. He joined the Volunteer army with 66 Hussar and 9 officers on October 26th 1918 from Tchugaev under the command of General Denikin.

By November 11, 1920, he was in command of the White’s Southern army’s cavalry but his regiment retreating from the Reds sustained heavy losses near Ushini and Karpovi Balky. the remaining forces left from Yalta to Gallipoli however, it is not clear if the Kotchoubeys were among Barbovitch’s officers who left from Yalta or whether they stayed in Sebastopol. Either way, many of the ships leaving Sebastopol would stop in Yalta.

A Logistics Victory for the Retreating White Army:

In addition to the propblem that there were more people than space available on the ships, the logistics challenges of embarking the fleeing armies and finding enough fuel to transport them on a 1-5 day journey through the Dardenelles without any official recognition from the countries on the route to Europe was a mission frought with potentiual disaster. The one element that could have created a humanitarian and military disaster was that the Red Army did not press their advantages and seemed to allow their soon to be former compatriots to flee. The irony of this moment should not be lost as the paradoxes of families being torn apart reached to the highest level of the military leadership. Admiral Berens brother became a Red naval officer and went on to serve in the Soviet navy after the Civil War.

Ushakov suggests that Red Army General Frunze was partly responsible for keeping the peace but others like Ushakov suggest that in fact it was the slow Soviet bureaucracy that was delayed in sending instructions and more importantly French contra Admiral Charles Henri Dumesnil (1868-1946) who was in command of the Eastern mediterranean French fleet who communicated with the military leadership of the Bolsheviks and threatened French reprisals should the flleing White army come under attack. On November 16th, Moscow’s feared head of the Secret Police, Feliy Dzherzinsky issued an order that no White officer was to be allowed to leave Russia but the order came too late.

The Southers Russian Governemnt, according to Ushakov’s article issued one of the following last communications ahead of the evacuation:

“Given the evacuation for willing officers, people serving the govenrment and their families, the government of South Russia considers it his duty to warn all those that the ordeals which await those fleeing from Russia. The lack of fuel will lead to more crowding on ships, and inevitably a long stay on the roads and at sea. Also completely unknown is the fate of the departing passengers, since none of the foreign powers have given their consent to the adoption of the evacuees. The Government of the South of Russia has no funds to provide any help in the way. All thoe people associated with the government who are not in immediate danger from the violence of the enemy, we advise to stay in the Crimea. “

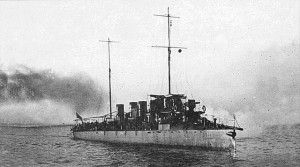

It is not clear what ship the Kotchoubey brothers and their wives were sailing on from Sebastopol or Yalta but as Vassili Mikhailovitch was traveling alone, he separated from his brothers and gave his assigned berth to a lady and her child. The fleet left Sevastopol on November 14, 1920 and then from Yalta on November 15th. In these ports, the embarkation process was more orderly then in other ports. All the ships, however were all overloaded with passengers. Vassya found a place on board the Destroyer “Zhivoy” which was a relatively new destroyer of the Lieutenant Puschtin class (names of this class of ships started with “Zh”) whose tonnage was between 350-450 and whose passenge manifest from November 15th suggested that there were 250 crew and evacuees aboard. The destroyer was ordered to be built by The Russian Imperial Navy in 1902 at the port of Nikolaev (Nikolaev Admiralty). It was launched on April 10th, 1920 and commissioned as the Ribetz in February 1906. At the end of WWI, it was captured by the Germans on June 19th, 1918 and then captured by the English and given to the White Army in December 1918. At his point it was renamed the “Zhivoy” and due to a lack of fuel and perhaps a defective engine, it was being towed by the “Kherson” which was orriginally built in 1895 and then renamed “Lena” in 1903 and then again “Kherson” after 1906. It was a large but old Destroyer with atonnage of 6,438. (after the evacuation, it became British and was named the Raetoria).

Conditions aboard most of the Wrangel ships were terrible. The ships were overflowing with passengers, the provisions were scant and in some cases there was enough food for only 1 day. People would be found sleeping everywhere including on deck. As one would expect with boat loads of Russians, there was drunkness and and the cossacks were among the nosiest and most boisterous of the passengers. It was a fitting prelude to the harsh world that was awaiting the Russian emigrés. Aboard the “Kherson” which pulled the “Zhivoy” there was allowance for one cup of soup which was watered down and stale crackers. Of course, there were cases of privileged ship passengers enjoying three course meals and living a relatively luxurious life en route to Constantinople.

Once aboard the “Zhivoy” which given its passenger manifest of 250 people could not have been as crowded as the other ships, Vassya did not have had time to settle comfortably as a violent storm blew off the coast of Sevastopol that night of November 15th, 1920. The storm severed the ships tow lines and the “Zhivoy” was separated from the “Kherson.” According to the weekly intelligence reports from Dumesnil’s East Mediterranean squadron’s flagship dated November 27th, 1920, the evacation was completed and all ships are accounted for with the exception of the destroyer “Zhivoy”, which was blown off course and was not accounted for at the time of the intelligence report.

Today we know that on the night of November 15th, the “Zhivoy” sunk in the storm and all of its declared 250 passengers (perhaps more) were killed at sea. The evacaution of the White Army was to confront many more hurdles and terrible conditions for the evacuees but it is one of the greatest achievements of that generation to mobilize enough ships and find enough fuel to cary the more than 145,000 people to a new life. Unfortunately, Vassya fate was exceptional in that he and his fellow passengers were the only people who died in this massive evacuation. One has to believe that this may have been part of a bigger plan to free Vassya from the terrible knowledge that he would somehow have to find a way back to his wife and his two young children whom he left behind in Kiev with his mother and sister. At the time of the evacuation, there was no clear way to make that happen. He was the first in the family to perish from the terrible events of the Russian Revolution and so his brothers were left without their eldest brother and his widow would have to find her own path with their two children. They would all remain in Russia and grow up and live in the Soviet Union. Ironically, only he and his youngest brother Sergei would leave descendants to carry on the family lineage.