(b. near Voronki, Tchernigov Province, Russia – d. Kiev oblast, USSR, December 19th, 1930)

Pelagea Dmitrovna Onoshko / Пелагея Дмитрьевна Онощко (1863-1930) was as her childrens’s second cousin Elena “Ella” Vladimirovna Tolstaya-Miloslavskaya (née princess Volkonskaya) / Елена Владимировна Толстая-Милославская (кн. Волконская) (1894-1984), the great granddaughter of the Decembrist prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonsky / Сергей Григорьевич Волконский (1788 -1865) would recall many years later, sitting in the comfort of her niece’s warm elegant home in Westchester county, New York, “La belle du village.” She was born and grew up in the village of Voronki where she fell in love with the local landowner, aristocrat, philanthropist and playwright, Mikhail “Mikhailo” Nikolaievitch / Михаил Николаевич Кочубей (1863-1935). Starting in 1889, she bore him five children and through a tumultuous relationship with her husband who was a notorious womanizer she managed to raise her children in the idyllic world that was Voronki. His mother was considered among the most beautiful women in the region and while her beauty & kindness won her the affection of Mikhailo, the villagers and of course their children, her intellect and stubborness helped save the estate of Voronki from being seized by creditors at a crucial time after Mikhailo ran away to St. Petersburg with the local scholl teacher from Voronki, Natalia Dmitrovna Tregubova in 1909 and left his estate in a state of heavy debt and near bankrupcy.

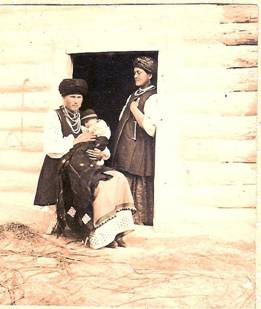

Pelagea was a proud woman who nonetheless refused to have her photograph taken. This was all the more remarkable given that Mikahil Nikolaivitch was an avid photographer. The photograph above is one of the only survivng pictures of her and may have been taken by Mikhail Nikolaivitch, himself. The other known photograph was lovingly kept in a small oval frame in the red corner of the home of her youngest son Sergei Mikhailovitch Kotchoubey (1896-1960) in his apartment in New York city. After his death, his children returned the photograph to Pelagea’s daughter Elena “Nelly” Mikhailovna Wickberg (née Kotchoubey) who lived in Canada. Sergei was cherished the photograph and cherished the memory of his mother who was remarkable in the same way as she was a silent oak in a family saga of betrayal and turmoil.

There was a big problem in the family. The dashing , handsome but unconventional aristocrat had not married his young, 25 year old village-girl lover even after she had given him his first child, Vassili in 1889. This behavior was unacceptable and years later Mikhail’s half-brother Sergei Dmitrievitch Molchanov / Сергей Дмитриевич Молчанов (1853-1905) (they were both sons of Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna (née Volkonskaya) / Елена Сергеевна Волконская (1835-1916) tried to push Pelagea to use this as a bargaining chip to get Mikhail to marry her. Unsuccessful, the duty turned to the towering figure of Elena Sergeivna who despite her convincing manner, and her forceful pleeding was not anymore effective in getting Mikhail to assume his familial responsibilities at least in name. Pelagea watched in a resigned manner as the family bullied, cajoled and raised their voices at Mikhail. She knew him too well and it would be impossible to tie that man down. It came to the newly enthroned Emperor Nicholas II to intervene on behalf of concerned family memebers to make sure that Mikhailo accepted the paternity of his five children and insure that they carried their names under legitimate circumstances. It should be noted that the Kotchoubey family were among the most influential people at the court of the last Tsar. Mikhailo made the necessary steps to officially recognize them and the matter was settled, however he never married the mother of his five children. Pelegea was loyal to her beloved village of Voronki but with her family she fled the estate in 1918 when it was seized by the Bolsheviks and while she spent sometime in Kiev, she died in the countryside at the end of 1930. Even with the departure of all her sons during the Russian Civil War, it was her daughter, Elena “Nelly” Mikhailovna Wickberg (née Kotchoubey) / Елена Михайловна Викберг (Кочубей) (1890-1972) and her granddaughter little Olga Dmitrievna Wickberg (1918-2007) that would remain near her until her death.

On her deathbad in the hospital in Hamilton, Canada, Nelly Wickberg with her family gathered around her, asked for the forgiveness of her sins. In the last hours of her life, she especially asked that her mother forgive her. Many years before, after the dark days of the Russian Civil war and in the years when Ukraine was plummeted into both a bloody class warfare and economic turmoil, her mother Pelegea developed tuberculosis. The horror of TB in the family was magnified by the death of baby Sergei, Nelly’s first husband Dmitri Axelievitch Wickberg / Дмитрий Аксельевич Викберг (1890-1924)‘s and her second husband. The devastation of loosing her eldest son and the fear of loosing her only surviving daughter forced Nelly to take drastic measures.

Her granddaughter, Olga Dmitrievna recalled many years later in Canada how her mother was walking near their house in Kiev in the late 1920s and a voice called out, “Barenya.” In those days of Soviet repression, a careless or intentional remark like that could end up with arrest, interoggation and a sentence to hard labor in the gulags or death. Nelly shuttered when she heard that word but could not help herself to turn around although she should have kept on walking. Before her stood a young girl whose mother had worked on the estate only a few years earlier and she recognized Nelly. The chance encounter was a small miracle as the young girl and her mother grew meager vegetables in the countryside and came to town to sell them on the street. Nelly agreed to buy some of the se vegetables and a friendship grew.

Conditions in Kiev in the late 1920s were difficult and food was scarce. More worringly, her mother had contracted TB and it was becoming increasingly difficult to care for her in Kiev. Maybe the country air would do her good. One day, she approached her new friends and arranged for her mother to live in the country with young woman in that way she could be cared for in the country and they would remain in contact when the young woman came to sell her vegetables. Pelegea passed away in the dark cold days of a December winter of complications from TB and the young woman made haste to the city to bring the news to Nelly. Olga remembered that there was no funeral service but she vividly remember as a young eleven year old girl the preparations for burial. Somehow, Pelagea’s bidy was returned back to her family and she was prepared for burial at home. With the curtains drawn and the minimal attention possible, Nelly would have said prayers for her mother but even the act of professing an Orthodox faith or the act of reciting prayers risked the attention of the NKVD so everything was done under the cover of darkness. A small coffin was made and Olga remembers bringing the body of her grandmother to the cemetary on a small sled pulled by her and her mother, Nelly in the hard packed snow that had been compressed by the cold winter of 1930. There they paid the guardians of the cemetary a few kopecks to bury the body in what may have been an unmarked grave.

Olga’s memory was already clouded with the pain of those terrible years of famine and terror in Kiev. Perhaps, Pelagea was buried at “Babyi Yar” a hallowed name for Ukrainian Jews who only a decade later would be murdered by the thousands and thrown into large ditches by the occupying German forces. Perhaps it was these repressed memories that Olga brought forward in her recounting of her grandmother’s burial but Olga remembered well the wails and cries in the night. She remembered how one of their friends and neighbors, an elderly Jewish professor was ordered to report at the central administration with his belongings. Olga remembered seeing him for the last time pushing a heavy wooden wheelbarrow full of the books that he could not part from even if it meant carrying them through the city on a wheelbarrow. So Nelly carried the memory of her mother dying in a small khutor probably not unlike the one where she was born and no family around her and only the faithful peasants to care for her in both her last days and in death. Sending her mother, Pelagea away to the country during her illness and death haunted Nelly for her whole life.