(b. Voronki, Tchernigov Province, Russia 5 January 1863 – d. Menton, France 1935)

(b. Voronki, Tchernigov Province, Russia 5 January 1863 – d. Menton, France 1935)

Mikhail Nikolaivitch /Михайло Миколайович (nom de plume: Mikhailo Vorontchuk / Михайло Вороньчук) was born on his parents’ estate (Nikolai Arkadievitch and Elena “Nelly” Sergeievna (née Princess Volkonskaya) that was called Voronki (Вороньки (Черниговская область). The estate is located in the southern part of the Tchernigov province which is north of Kiev (today Bobrovitskiy Region) on the banks of the Supoi river. Even today, it is renowned for its unspoilt beauty and incredible nature. As of 1782, the property belonged to the Miloradovich family who paranthetically married into the Kotchoubey family in the early 18th century. It was purchased by Arkadi Vassilievitch for his son Nikolai in 1850. The land is characterized by vast plains punctuated by stands of pine trees which are separated by meandering rivers and streams and beautiful lakes. The village which has just over 1000 inhabitants today is of little historical significance except that the Kotchoubeys lived there and the fact that the Decembrist, Prince Sergei Grigoriovitch Volkonsky and his wife, Princess Maria Nikolaivna (née Raevskaya) both died and were buried on the estate. There is a contemporary commemorative monument to them and their fellow exiled Decembrist, Alexander Poggio but the original chapel designed by Alexander Yagn and gravestones were destroyed in the 20th century.

This region is in Ukraine and for 400 years it was part of a geographic region that was historically tied to the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The first Kotchoubeys to arrive in the region in the early 17th c. settled in and around Baturyn, which at the time was the capital of Tchernigov. The family played an important part in the history of this illustrious Cossack host, Imperial Russia and establishing Ukraine’s brief independence under the last Hetman before the rise of the Soviet Union.

Upbringing:

Mikhail who will be referred to as Mikhailo for his pro-Ukrainian sympathies was a father, a playwright, a philanthropist and a free spirit. He was his father’s only surviving child but he was far from being the only child as his mother married Nikolai Arkadievitch with two children from her first marriage to Dmitri Vassilivitch Molchanov (b. to d. 1857) (Дмитрий Васильевич Молчанов). Mikhailo would have two additional step-sisters from his mother’s third marriage to Alexander Alekseevich Rakhmanov (b. 1830 – d. 23 December 1916) (Александр Алексеевич Рахманов), -Maria Dmitrivna and Olena Dmitrivna Rakhmanova.

A Web of Family Relations:

No doubt, Mikhailo was the spoiled and cherished offspring of both of his parents. His father, Nikolai endured much heartache in his life having lost his mother when he was only seven when she died of cholera along with Nikolai’s 6 year old brother, Viktor, in 1834 in Orel. Years later he fell in love and married the beautiful Ekaterina Arkadievna (née Stolypina) / Екатерина Аркадьевна Столыпина(1824-29 March 1852). They were married in a grand wedding that was feted by all of St. Petersburg in 1849 but their marriage would be brief as again he would be denied happiness when on tour in Italy, Ekaterina Arkadievna and their infant daughter, Vera Nikolaievna (b. 12 April 1851 -d. 21 April 1852) died within a few weeks of each other in April 1852 in Pisa, Italy. Nikolai was inconsolable and he ordered a beautiful monument to his daughter to be erected in St. Petersburg’s Alexander Nevsky’s Lavra cemetery where it stands today, a testament to the loss of a beloved child, a beloved wife and a love that was torn from him too early.

Nikolai spent his formative childhood years between St. Petersburg and Orel where his father was the Governor from 1830-1837. Not far from the city was the estate of Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, the home of Ivan Turgenev. Yasnaya Polyana, the home of a related branch of the Volkonsky family which was inherited by Lev Nikolaevitch Tolstoy from his mother was also a few hours ride by carriage from the city. Years later, Lev Nikolaeivitch would vist his cousin Elena Sergeievna on her estate as he would be tormented by his unfinished novel, the Decembrists. Within the closed knit social world of Orel, Nikolai became a childhood friend of Ivan Turgenev who years later introduced him to his second wife Elena Sergeievna. That year was 1858 and it was love at first sight. They married that year and soon welcomed their first son Alexander Nikolaivitch (1859-1861) who was born in Voronki. It was an idyllic time for the family who together with the Volkonsky parents-in-law set about establishing themselves on the beautiful estate. Tragedy struck again and young Alexander dies in 1861 at the tender age of three. Mikhailo would become their only surving son after he is born in 1863. The joy of his birth is already marred by Nikolai’s health which takes a turn for the worse as he begins to show obvious signs of Tuberculosis.

Mikhailo was not considered to be an intelligent child but he had, what could be described, as a fairly conventional upbringing for a Russian nobleman. Of course the fact that his mother, Elena Sergeievna, was the daughter of the towering figure of the Russia’s Decembrist movement, Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonsky, meant she was born and raised in Irkutsk, Siberia during part of her parents’ exile. Elena Sergeievna’s childhood was anything but convenetional and her subsequent return to European Russia with her parents would mark Mikhail both in his unusual relationships with his family and his love of theatre and literature.

This passion for the theatrical arts was not incidental. Many years before his birth, his grandfather Arkadi Vassilievitch still in the throws of youthful enthousiasm for literature and philosophy, wrote with his friend Count Sergei Pavlovich Potemkin / Граф Сергей Павлович Потёмкин (1787-1858) a number poems as well as selected translations of Racine and he co-wrote in 1808 Cherie / Душенька, (see: Duschenka) an opera in 5 acts. The publication was genereously underwritten by Potemkin who provided additional funds for illustrations. The opera was based on a work by the Russian poet, Ippolite Fiodorovitch Bogdanovitch (1744-1803). 1 Potemkin and Akadi Vassilievitch were both educated in St. Petersburg at a boarding school run by Abbott Nikolia and their education in French and the years at boarding school insured a shared love of language and a friendship that would last until Potemkin’s early death. The friendship was reinforced by the marriage between Potemkin’s uncle Piotr Sergeievitch Potemkin / Пётр Сергеевич Потёмкин and Nadezhda Semienovna (nee Kotchoubey) / Надежда Семёновна Кочубей. He initilaly lived in Moscow and was, of course, the nephew and god son of the legendary Grigory Potemkin, Catherine the Great’s alleged husband. 2

His Grandmother, Princess Maria Nikolaievna Volkonsky’s (née Raevskaya) salons in her home in Irkutsk were renowned for their focus on music, literature and philosophical debates. She along with her husband both wrote their memoirs, while Prince Sergei Grigoriovitch a classmate and childhood friend of Nikolai’s grandfather, Arkadi Vassilievitch and his brothers wrote a number of additional works. When Princess Maria Nikolaievna joined her daughter at Voronki from Siberia, she set about building a theater and introducing an important artistic tradition that would last until the revolution. While Mikhail could not have been directly influenced by his father’s love of literature as he died when Mikhail was two, Nikolai Arkadievitch was a close friend of the poet Prince Pyotr Wiazemsky and as mentioned above, Ivan Turgenev. These and many other of his late father’s friendships would give Mikhailo an intimate access to the vibrant literary circles in both Russia and increasingly Ukraine’s own indebendent literary groups. In later years, Turgenev and Nikolai’s widow, Elena Sergeievna would carry on a fascinating correspondence and no doubt Mikhailo was a witness to these wonderful exchnages.

Mikhailo’s father, Nikolai left Ukraine and Voronki to live in a more humid climate with the hope of d in the last years of his life in Venice and died of tuberculosis in 1865 in the family’s beautiful palace purchased by him and his second wife Elena Sergeievna on their honeymoon in Venice in 1860. A beautiful poem about Venice by Wiazemsky is dedicated to him. The palazzo with its beautiful garden is on the Dorsoduro overlooking the Guidecca Canal. As a result of his father’s death, Mikhail would float between various father figures throughout his life. His mother, a vibrant and highly learned woman was happiest in the company of men. This may in part explain his own tortured and unexplainable relationships with his own children and his wives.

Philantropy.

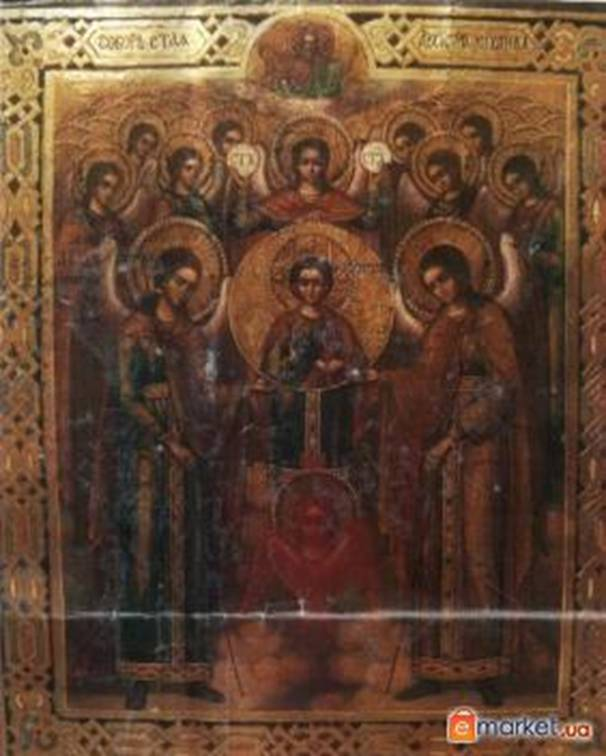

In 2008, in an online auction an icon of The Cathedral of the Archangel Michael / Собор архистратига Михаила appeared at auction.The icon was probably a copy but being passed off as an original made by Victor Mikhailovitch Vasnetsov / Виктор Михайлович Васнецов (1848-1926) and dated from the last quarter of the 19th c. It remains to be seen if there can be documented evidence of this icon being written and sold to the the Society which then gifted the icon to Mikhail. The icon was advertised as being on cypress board and with tempera paint and gold. Dimensions were 27.4 x 20cm. Some of Vasnetsov’s icons did not have canonical status as they were drawn in a realist style. As such they have decorative value but the icon of the Cathedral of Archangel Michael if indeed “written” by Vasnetsov follows the canonical traditions. The icon would have hung in the church on the Voronki property or at home and was certainly looted in 1918. The icon was interesting for four reasons.

1) It may have been the work of the famous Russian artist Vasnetsov / Васнецов from the famed artistic family and the man who had just completed the frescoes for the newly built St. Vladimir’s cathedral in Kiev. Vasnetsov worked on the project from 1884-1889.

2) It was a gift to Mikhail Nikolaievitch from the representatives of Peasant Land owners and Cossacks dated 1895 with the following inscription “To his Excellency, Mikhail Nikolaivitch Kotchoubey from the representatives of the society of pesant landowners and cossacks.” description by the sellers:

На обратной стороне доски имеется пространная дарственная надпись, из которой следует, что в 1895 году она была преподнесена в дар «Его Высокородию Михаилу Николаевичу Кочубею от представителей Общества крестьян-собственников и казаков» (список их фамилий дается в этой надписи). Надпись заверена подписью Вепракского священника Василия Диаковского и скреплена круглой церковной сургучной печатью.

3) the sellers were looking to sell the icon for between $1 and $1.5 million. Given that this was still 2008, maybe that was a fair price….

4) on the back the icon is certified by the Vepraksky priest Vassili Diakovskiy and while there a number of sources that lead one to trace a priest with a similar name as one Vassili Grigorievitch Diakovskiy / Василий Григорьевич Диаковский whose fater was also a priest in Herson. Vassili himself graduated from seminary and then taught at the Herson Seminary and then became a priest in Lubomirka in the Saint Trinity Church. It is impossible to determine for sure the appropriate association but Vasnetsov did have several ties to Herson including a portrait of the Herson Museum’s founder. Perhaps the icon was originally destined for a church i n Herson and the certfication stands as a stamp of authenticity. The mystery remains in place. / (Надпись заверена подписью Вепракского священника Василия Диаковского и скреплена круглой церковной сургучной печатью.

A seemingly small icon with a huge message. Mikhail may have been a lot of things but he was a true bnefactor and philanthropist. He helped establish schools all over Tchernigov and from the forgotten archives of history an incredible story of charity has emerged.

Twists of Fortunes and an Unconventional Family

Mikhail’s uncle Piotr Arkadievitch was the designated ward of Mikhail’s important inheritance. In 1865, Mikhail would become the heir to his father’s estate, Voronki and a year later he would additionally receive the estate of Kishnorvka near Borza which was willed to him by his childless great-uncle, Alexander Vsssilievitch (1798-1866). In the archives of the State Mueseum of the Volkonsky house in Irkutsk, Sibera are letters that attest to the tensions between Piotr Arkadievitch, whose strict administration of the estate and budgetary discipline was becoming a real inconvenience to the free spending Elena Sergeievna.

The Bezborodko, Repnine factor

At this juncture, we need to look back into some important historical events that would come winding its way into the cozy world of the Kotchoubey-Wolkonsky marriage like Japanese knotweed which once rooted in a garden seems to become a constant companion to the plants, even suffocating them. Years before, two importnat people and one important event would play a role unbeknownst to them in the fate of Elena Sergeievna’s stay in Voronki. The first is the Chancellor Alexander Bezborodko among many august roles he was responsible for Ukraine under Catherine II and he took upon himself the responsibility of raising young Prince Viktor Pavlovich (1768-1834) and his brother who were both left fatherless at a young age. Viktor Pavlovich who was married to Princess Varvara Vassiltchikov in turn raised Mikhailo’s grandfather Arkadi Vassilievitch (1790-1878) and one of his brothers when they, too lost their father in 1800 when Arkadii was only 10 years old. Certainly due to the close relationship to Prince Viktor Pavlovich’s family and the years spent in their company, Arkadi’s met his wife at an a ball in St. Petersburg who was the daughter of Princess Vassiltchikova. This must have overjoyed the Prince and Chancellor Viktor Pavlovich and his wife who would proudly watch both their nephews embark on a long illustrious path in governement service and would become an important mentor the family. Bezborodko died childless but his fortune passed to his nephew and eventually his great grand niece would marry Piotr Arkadievitch. A secondcloser figure was Prince Sergei Grigorovitch Volkonsky. He was, of course Mikhailo’s grandfather. Year earlier several important moments took place. Firstly, Prince Sergei’s mother was the last of the powerful and storied boyar family, the Princes Repnine. Emperor Alexander I proclaimed that Prince Nikolai Grigorovcitch, Prince Sergei’s brother would carry his mother’s name and he became Prince Nikolai Grigorovich Repnine-Volkonsky. childles The relationships within the small world of the family were further complicated by the fact that Piotr Arkadievitch was married to Barbara Alexandrovna (née Kushelev-Bezborodko) whose mother Alexandra Nikolaevna (née Princess Repnina-Volkonskaya) was Elena Sergeievna’s first cousin. The family ties aside, there was concern on the part of the Kotchoubey’s about the amount of money that Elena Sergeievna was spending and in addition she had decided to marry a third time, a minor landed nobleman who was also Voronki’s estate manager, Alexander Alekseevich Rakhmanov (b. 1830 – d. 23 December 1916) (Александр Алексеевич Рахманов). He was probably related to Varvara Nikolaevna (née Rakhmanova (Варвара Николаевна Рахманова) (?-1846) who was married to Nikolai & Piotr Arkadievitch’s uncle, Vassili Vassilievitch. It was decided, most likely by Piotr Arkadievitch that they would buy her Veisbokhovka which was 30 km away and next to Varvarovka, another Kotchoubey estate. This would isolate her spending activities into a manageable quantity and allow her to build a home separately with her new husband. What ever the distances, the families would remain close as the grew and the distances seemed not to affect the visits to each other.

Ultimately, Elena Sergeievna moved out to an estate bought for her by Mikhailo called Veisbokhovka. Throughout these conflicts, Mikhailo was not overly concerned with his money and this trait would eventually cause a great rift between him and his family. Still, until he was 15, Mikhail’s grandfather, Arkadi Vassiliovitch, was alive and although he was living in St. Petersburg, he frequently visited Zgourovka, the family’s seat received as a dowry from his marriage to Sophia Nikolaevna (née Wiazemsky) and the place where Piotr Arkadievitch lived.

The relationship that existed between uncle and nephew as well as the proximity of the various Kotchoubey estates ensured that Mikhail was welcomed into his larger Kotchoubey family. With time, he would maintain a strong bond with his uncle Piotr Arkadievitch, his wife Barbara (née Kushelev-Bezborodko) who was Elena Sergievna’s first cousin and their children. In the end, Elena Sergeievna’s relationship with Mikhail was special and his own bohemian, free-spirited character was perhaps closest to her own. As he was often absent, she would go on to help raise his five children. Upon hearing that he was leaving for France, Nelly suffered a stroke and was wheel chair bound after that. She was devastated and until her death, on December 23, 1916, she would never be the same.

Finances:

Mikail was not particularly careful about his finances. His children would never carry any money and they lived happily on credit. Whenever any of the children incurred an expense they would just say who they were and Mikhail would be billed. The local bank was jokingly known as Kotchoubeievsky bank because the same invoices were paid multiple times. It appeared that Mikail did not practice strict accounting controls. He inherited the estate of Voronki from his father and then in 1866, he inherited Kishnorvka near Borza, an estate owned by the Kotchoubeys since the 18th century and that passed to Alexander Vassilievitch who dies childless. The estate brough Mikhailo to visit the region and he was eventually elected marshal of the Nobility for a three year period. He was known to build school and theaters but his charity would not insulate his form the angry peasants who lead a damaging revolt from 1905-1907. While his cousin’s estate, Zgourovka was burned to the ground, Vassili Petrovich was able to rebuild his relationships with the peasants and rebuild. Mikail was too interested in art, cars and other pursuits to attempt to repair the damage wrought from this tumultous political era and he sold his estate in 1906. Russia was enetring its last goleden age and its economic strength lead to a peak in agricultural production in 1913. In the years, after 1906, Mikhailo was spending more time with his new wife, Natalia Dmitrovna and he left Ukraine for good in 1909 for St. Petersburg and then in 1913 he left the Capital for France. In his wake, he left his family’s finances in complete dissary. What happened with the 400,000 rubles he received from the sale of Kishnorvka is unclear but Pelegeia Dmitrovna took out a mortgage on Voronki in her own name to keep it from falli9ng into the hands of creditors.

Literature, Theatre and the Ukrainian Renaissance

Perhaps because of liberties that the arts afford a man who walks the narrow path as the scion of a great family and an outsider-rebel, Mikhail did not hide his love for Ukraine, its language or its culture. He was raised primarily on his estate and enjoying a warm friendship with his broader Kotchoubey family, Mikhail not only engaged Ukrainian society on a social level but became great friends with writers and nationalists like Panteleimon Kulish. The friendship blossomed in the late 19th c. on the eve of Mikhail’s appointment as Marshal of the Nobility in Borzna where Kulish died in 1897. These relationships were not without their challenges as Ukrainian culture was largely repressed by agents of the Imperial government for its pro-Ukrainian character. Like his grandfather, Sergei Volkonsky, Mikhail in his own way did not cow to the quasi-repressive nature of the Russian state or let himself be intimidated by pro-Russian policies.

Photography, Cars :

Mikhail was an avid photogrpaher. His picture below taken at Voronki and entitled “Bords du Soupoi” was chosen along with 21 other photagraphers to represent Russia and his photograph was included into an 1894 Photography Exhibit called the “Première Exposition d’Art Photographique” of the Photo-Club of Paris (1894). The original Plate and print by M. Fillon of the ateliers LeMercier & Cie, Paris.

Bords du Soupoi 1894

Mikhail’s son, Sergei would often reminisce about his father’s first car and how it would get stuck in the mud and required to be pulled out of the mud and down the road by a team of oxen. At the turn of the 20th century, luxury cars were exclusively imported from France. The French and the Swiss were among the leading auto manufacturers. Long after this time, Mikhail’s son Mikhail would be reluctant about going inside a Parisian car dealership as he feared it would open a Pandora’s box. He was aware that they knew him as the son of a very big client and the first purchaser of this make in Russia. Were there debts left unpaid? Perhaps Mikhail who was estranged from his family was living in Paris and still a client? We will never know.

A New Chapter: France

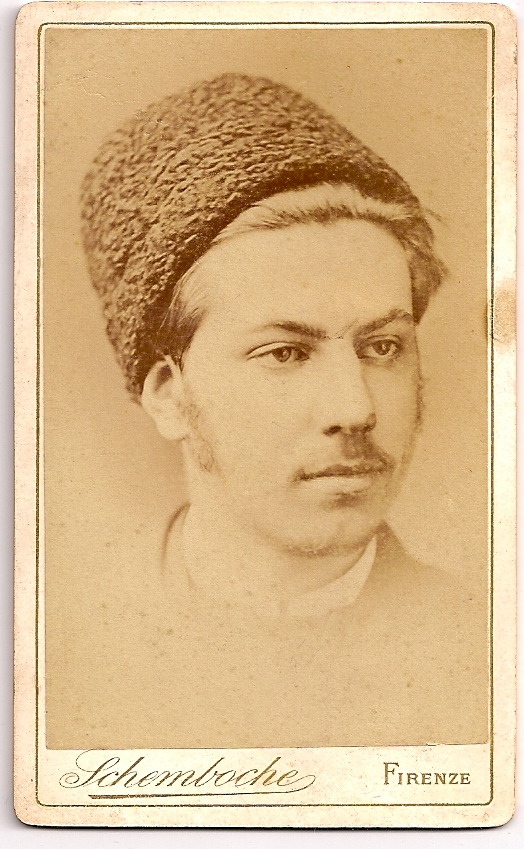

It seems that one never actually fully succeeds in running away. Even if Mikhailo never saw his family again after leaving Russia for France in 1990, his son, Sergei would be haunted by unusual moments of serendipty that would remind him in the most unexpected ways of his father’s memory. When living in Florence in the 1930s, he visisted the photographers Brogi & Schemboche in Florence for his own needs as an opera singer. One of the owners recognized his name and pulled from their archives a photograph of Mikhailo which was taken in the late 1880s on one of his visits to Florence and he gave it to Sergei. Mikhailo may have still been alive at that point and as a photographer may have even retained contact with the storied photography shop in Florence. Florence was after all an important city for the family as his half-sister, Elena “Alyona” Alexandrovna Rakhmanova was born there in 1873 during one the many visits undertaken by her mother Nelly.

It seems that one never actually fully succeeds in running away. Even if Mikhailo never saw his family again after leaving Russia for France in 1990, his son, Sergei would be haunted by unusual moments of serendipty that would remind him in the most unexpected ways of his father’s memory. When living in Florence in the 1930s, he visisted the photographers Brogi & Schemboche in Florence for his own needs as an opera singer. One of the owners recognized his name and pulled from their archives a photograph of Mikhailo which was taken in the late 1880s on one of his visits to Florence and he gave it to Sergei. Mikhailo may have still been alive at that point and as a photographer may have even retained contact with the storied photography shop in Florence. Florence was after all an important city for the family as his half-sister, Elena “Alyona” Alexandrovna Rakhmanova was born there in 1873 during one the many visits undertaken by her mother Nelly.

Of the many factors that defined Mikhailo was his inability to resist female charms and as such he was a notorious womanizer. The family lost touch with him after his departure from Ukraine and it is difficult to understand the circumstances for his decision. Perhaps, he was concerned about his links to writers and politicians who were associated with a pro-Ukrainian movement or he was faced with the challenges of insolvency following the tumultuous 1905 uprising. More likely, it was the pressure that he was feeling from his mother Nelly Sergeievna to marry the mother of his five children. Recognizing them as his children was not enough for his family who while liberal in their sentiments understood the gravity of Mikhail shirking his responsibilities as both an heir to a great family and the father of five children. No amount of pressure could convince him to the right thing and the sad consequences of his stubborness had far reaching impact on his family. In refusing to marry Pelegea and the consequential decision to leave Voronki were two blows that his mother could not take and she suffered a minor stroke which left her wheelchair bound until her death in December 1916. She used the same wheelchair as her father, Prince Grigory Semionovitch and it was a reminder of the obstinate traits in the family that had sent her father to exile in Siberia after refusing to apologize to his childhood playmate Emperor Nicholas I for Grigory’s role in the Decembrist uprising and now her son, Mikhail who driven by his convictions forced himself into a self-imposed exile to France. Mikhail’s decision may not have been so much a lack of willingness to do the right thing but perhaps his eagerness to start a new life with a with Natalia Dmitrievna (née Tregoubova) (? -d. 27, January, 1941) who was a school teacher in the local school of Voronki. They departed for St. Petersburg in 1909 and then France in 1913.

Settled in France, Mikhail continued to try and care for his family in Russia. He would have certainly learned of his sons participation in the Civil War and their arrival in Europe. After all, Paris and France by extension was a hive of activity of Tsarist officers and Russian White émigrés who frequently spent time together. Mikhail sent packages to the Soviet Union with foodstuffs and letters. There is no knowledge that these packages were received and his daughter Nelly who remained in Kiev never mentioned receiving them. Any outgoing mail was surely intercepted by the NKVD who tightly controlled the borders and especially the post. Perhaps Natalia Dmitirevna, perhaps now his wife in a fit of jealousy hid the letters for Mikhail but whatever the facts, he was to be forever separated from his family.

Article on Mikhailo Kotchoubey (Ukrainian)

Sources:

1. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arkadi_Vassilievitch_Kotchoube%C3%AF

http://esu.com.ua/search_articles.php?id=1288

http://uk.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Кинашівка_(Борзнянський_район)